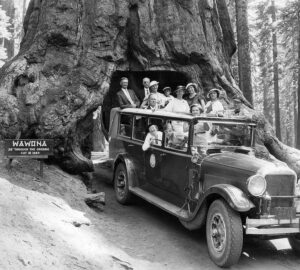

It’s not often that I hear about a creature more resilient than redwoods. After all, they grow faster, live longer, and reproduce more prolifically than just about any other tree. Be that as it may, some very small, unassuming creatures of the (recently less) frozen north may lay claim to the title of Toughest Plant Alive.

While monitoring the recession of the Teardrop glacier (located on Ellesmere Island in Nunavut), a team of Scientists from the University of Alberta found that the melting ice exposed over 60 species of plants that had been frozen for 500 years (since the glacier was at its maximum during a period known as ‘the Little Ice Age’). Amazingly many of these plants were not dead, but merely dormant. Many plants showed green tips and new shoots despite being uncovered for less than a year and with the glacier’s edge only a few centimeters away. Lab studies confirmed that this new growth was not the result of seeds establishing on the frozen plants, but was the original plant itself, not dead, but merely dormant!

This is not only an extremely cool discovery, but it also raises some interesting questions about how our natural ecosystems might adapt to a changing climate. The team’s lead investigator concludes that plants uncovered by glacial ice can “serve as an unrecognized genetic reservoir.” These “genetic reservoirs” are vitally important to maintaining species’ diversity, resilience, and adaptability as conditions around them change. We don’t have any melting glaciers in the redwoods, but where else might we find those reservoirs—in the vigorous young industrial timberlands of Mendocino County? In the sprouts still appearing at the base of a long-cut stump in a suburban backyard? On the gravelly loams of Monterey or the alluvial flats of Del Norte? The answer is, unsurprisingly, all of the above. Redwoods’ genetic reservoirs haven’t been buried under centuries of ice, and are all around us, hidden by their youth and location. We don’t know which of these trees will handle the coming changes with ease and which will struggle, and so the best we can do is to hedge our bets and work to conserve redwood forests in all the places they naturally occur. With so much uncertainty surrounding California’s climate and the ability of our forests to adapt as it changes, saving the ancient forests of the future means keeping all of nature’s genetic options—its means of survival—open.

Want to learn more about climate and redwoods? Check out our Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative!