Wendy Baxter and Anthony Ambrose from Todd Dawson’s Laboratory at U.C. Berkeley have been tracking weather in the League’s Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative research plots in the coast redwood and giant sequoias forests. Check out their latest weather report below and learn more about the climate study here.

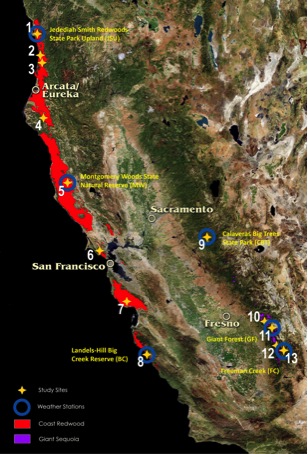

Have you been wondering how the current historic drought has impacted California’s majestic coast redwood and giant sequoia forests? We’ve been collecting weather data in six forests (Figure 1) as part of the Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative (RCCI) for several years now. Here’s a brief update on how the drought has affected environmental conditions in these forests.

The weather stations have been collecting data at some of the forests since 2011 and in others since 2012, so we don’t have that many years of site-specific data yet to put this drought into context. However, in the few years we have been monitoring the climate, there are some noticeable differences between the years.

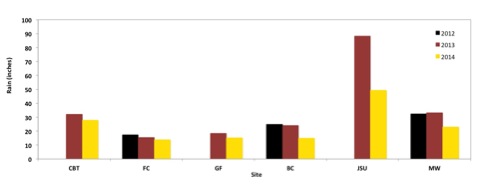

At all of the sites, the amount of rain that fell during the 2014 water year (October 1, 2013 to September 30, 2014) was less than the previous water years we have measured (Figure 2).

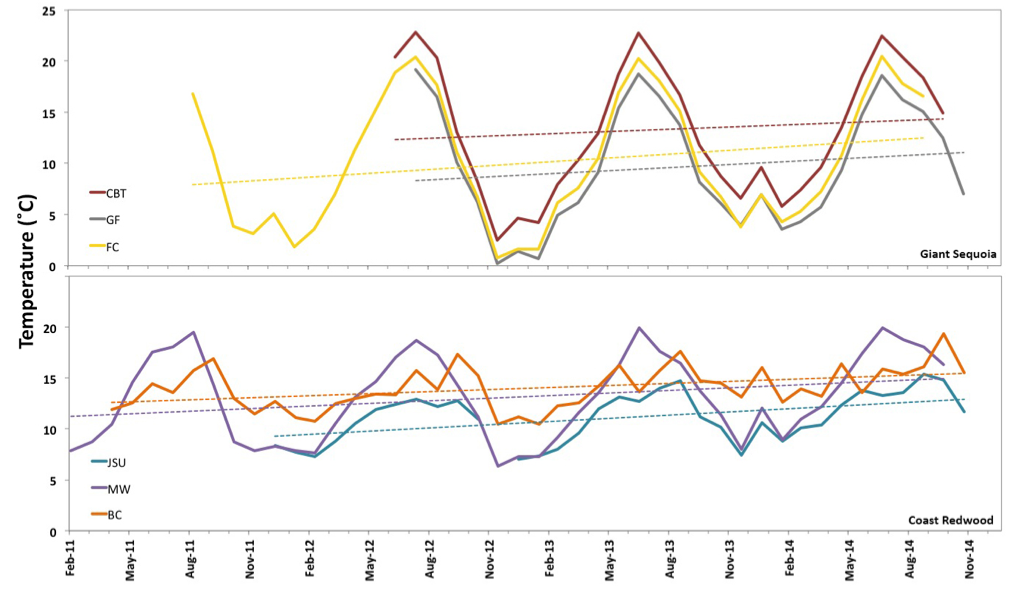

There also was a slight increase in average treetop temperatures (Figure 3) and a decrease in average relative humidity over this same time. Winter temperatures have increased more dramatically than any other season. This has implications especially for the giant sequoias, which depend on snowfall to slowly release water into the soils as the snow melts. When winter temperatures are warmer, and less precipitation falls as snow, the snow pack is less and the snow melts earlier. Temperature and humidity together determine the evaporative demand, or dryness of the atmosphere. A drier atmosphere causes plants to draw more water from their roots, which over time can reduce the total amount of soil water available to plants. Our data reveals that at all sites, except for Calaveras Big Trees State Park, average soil moisture has decreased over the last few years.

What does this all mean for the individual trees and the forests as a whole? Redwoods are incredibly resilient and can live for thousands of years, and it’s likely that many of the older trees in these forests have endured similar droughts in the past. Many giant sequoia trees, particularly in southern forests, were observed to be dropping a lot of their foliage in the summer and fall of 2014. Some local residents in the southern part of the coast redwood range also observed what appear to be increased levels of foliage die-back. This is something that happens every year, as the trees shed older foliage, but it seems to have happened earlier this year and the trees seemed to be dropping more foliage than in past years. This is likely a strategy the trees employ to reduce their need for water. But it’s also a sign of stress. It’s important to continue to monitor these trees and the climate they are living in, so we can better understand how they are responding to changing conditions.

2014 was the third consecutive year of severe drought in California and as of early February 2015, 77% of the state was still considered to be in extreme drought. Although we had a good start to the rain year with substantial rains in early December, January has proven to be a very dry month. Snowfall in the Sierra Nevada mountains, which giant sequoias rely on, has been exceptionally low so far this year as well, with only about 31% of normal snow water content. It’s still uncertain how the rest of the rain and snow season will shape up, but we’ll be keeping an eye on these forests and get back to you with another update soon!

Be sure to learn more about our Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative.