Studies show time in the woods can boost our immune systems and lower anxiety, depression, and anger, but discrimination may undermine these benefits

The trail at Reinhardt Regional Redwood Park in Oakland is scattered with the shed needles and threads of redwood bark that drift from the full canopy above. These groves sprouted from a recent traumatic past—the trees are the descendants of old-growth redwoods that were logged almost to nonexistence.

How might these redwood younglings help humans thrive amidst our own complex traumas?

One answer might lie in the ways in which forests like this can literally heal us.

In 2010, the Japanese journal Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine published a series of studies conducted between 2005 and 2008 on Japanese adults who spent three days and two nights in local forests, exploring the effect of Shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing, on the immune system. In study after study, researchers found increased production of cancer-fighting cells (“Natural Killer” or “NK” cells), decreased concentrations of adrenaline and cortisol in urine and saliva samples, decreased blood pressure, and decreased self-reported scores for anxiety, depression, and anger.

Over the past decade, more data has accumulated. In 2012, a group of elderly adults with hypertension in China spent seven days in a forest. At the end of the study, a significant drop in blood pressure was measured in the participants.

The health impacts of nature are likely not limited to forests. A 2015 study found a correlation between increased access to nature and a decrease in crime rates in U.K. neighborhoods. A 2015 Stanford University study about the impact of urbanization on mental health showed that walking in nature decreased negative rumination in adults.

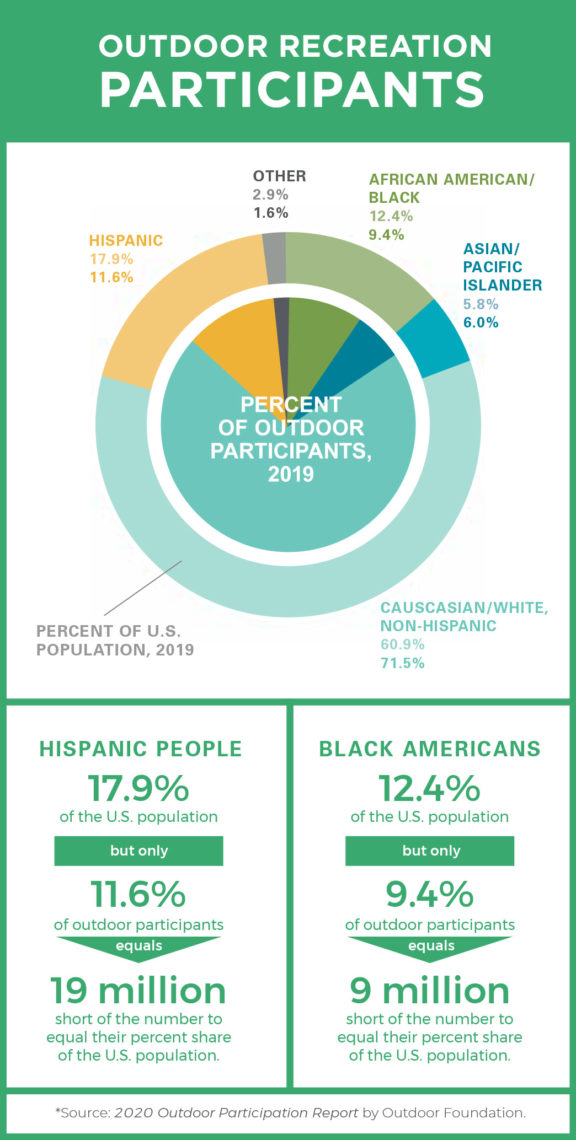

A paradigmatic shift may be underway in how modern science understands the role nature can play in medicine. But whether people of color in the United States stand to benefit from this shift is not as clear. While people of color are disproportionately impacted by ailments that time in nature might alleviate—cancer, hypertension, and inflammatory diseases like asthma—racism in outdoor spaces may present a barrier to access. At 71.5%, most American outdoor recreation participants in 2019 were white, followed by Hispanic people at 11.6%, Black people at 9.4%, and Asian people at 6%, according to the 2020 Outdoor Participation Report by Outdoor Foundation. Black and Hispanic Americans remained significantly underrepresented compared to their share of the nation’s population.

When people of color do spend time in nature, it may lead to stressful interactions, according to Leticia Márquez-Magaña, a professor of Cell and Molecular Biology and the Director of the Health & Equity Research Lab at San Francisco State University. She speaks about the ways in which systemic racism can result in chronic stress and wreak havoc on the immune system. Márquez-Magaña believes these impacts can be ameliorated by time in nature—but only if it does not become an additional source of stress.

“Walking, breathing deeply, all of that can reduce cortisol, which is the stress hormone. Being in nature with others can promote the production of dopamine, the happiness hormone,” she says. “What doesn’t work is walking in nature and having someone say, ‘You don’t belong here, you have to get out.’”

For time in nature to benefit everyone, we need to understand its impacts on everyone. This means more research to address a gap in the field. “In terms of the research,” Márquez-Magaña says, “there has been very little done on people of color in the U.S. around the benefits of nature. The way the environment changes as a result of your skin color affects many, many, many things.”

To measure some of these things, Midley Michaud, a graduate researcher in Márquez-Magaña’s lab, is leading a pilot series of studies on the impact of nature on people of color. Michaud says, “Something has been done to Black people in nature, and they are afraid. If white people are in nature, and they are a trigger, then that will affect people.”

Victoria Thompson, an outdoor educator, grew up in the redwoods of Berkeley and trekked the Sierra Nevada as a kid with her parents. Thompson is white, and when discussing how race might shape one’s experience of the outdoors, she offers, “White people can have expectations about being in nature, ‘I don’t want anyone to bother me.’ What I can remember—if I find myself getting annoyed—is that I’m not more entitled to this space than anyone else.”

On the Stream Trail, Reinhardt Redwood Regional is a site of sociology as much as ecology. There are identifiably Black, Asian, and Latinx people, multigenerational families, and youth groups; English, Mandarin, Spanish, and Bengali are spoken. In the words of Márquez-Magaña: “For many members of communal cultures, nature is part of the thinking that ‘I am, because we are; I exist because you exist.’”

Redwoods are healthiest alongside other redwoods. Cut down one tree, and the remaining trees are affected. Over time, we learned that for redwoods to thrive, we needed to nourish entire communities. Could we be likewise stewarded, growing healthier as parts of an interconnected whole, trusting that the well-being of one contributes to the well-being of all?

Given enough time, our very biochemistry is altered by forests. Perhaps our behavior can be altered as well.

HEALTH BENEFITS OF VISITING FORESTS

WHAT

Studies have shown that spending time in forests boosts visitors’ cancer-fighting cells and reduces blood pressure, anxiety, depression, and anger.

BARRIERS

Discrimination in outdoor spaces may block access to the health benefits for people of color. Most American outdoor recreation participants are white; Black and Hispanic Americans are significantly underrepresented compared to their share of the nation’s population. When people of color do spend time in nature, it may lead to stressful interactions.

NEW STUDIES

Research on the impact of nature on people of color is underway at San Francisco State University.

This feature appears in the beautiful printed edition of Redwoods magazine, a showcase of redwoods conservation stories by leading scientists and writers, as well as breathtaking photos, and ways you can help the forest.

Join our thousands of members today for only $25, and you’ll get future editions of our Redwoods magazine.