Critical coho salmon habitat at 'O Rew is rebuilt for fish and forest to thrive

Coho salmon spend most of their adult lives roaming the Pacific Ocean, from sunlit shallows to the crushing blackness 800 feet below. In a near-constant state of growth—the biggest coho can reach 3 feet in length and weigh more than 35 pounds—they range as far as 1,000 miles through open seas, fattening up on prey such as anchovies and crustaceans.

Before this ocean journey can begin however, coho salmon hatchlings need a safe place to feed and prepare for life beyond the stream. With coho populations dwindling along California’s North Coast, providing juvenile coho with such a haven has become more critical than ever.

One of the West Coast’s most important nurseries for young coho lies along the Prairie Creek floodplain as it winds near Orick, California. Once the site of a lumber mill, the floodplain is a flat valley surrounded by the forests of Redwood National and State Parks. These are the ancestral lands of the Yurok people. They call this place ‘O Rew.

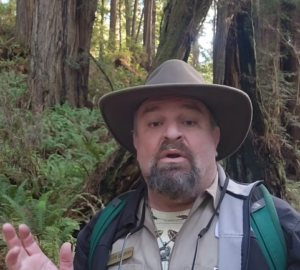

In November, Save the Redwoods League celebrated the completion of a five-year transformation of Prairie Creek at ‘O Rew. Working with the Yurok Tribe, California Trout (CalTrout), the Wildlife Conservation Board, California State Coastal Conservancy, and other agencies and funders, the team turned the crumbling mill site into a vital nursery for young salmon and other aquatic creatures.

It’s one of the most ambitious restoration projects in the region, and it was powered by partnership.

“All the groups pulling together to make this project happen sort of reflect the reciprocal relationship between the redwoods, fish, and water,” says Jessica Carter, director of parks and public engagement for Save the Redwoods. “We achieved amazing results on this restoration—together.”

What a salmon needs

Juvenile coho—as well as the other ocean-going fish that spawn in Prairie Creek, including Chinook salmon, steelhead trout, and coastal cutthroat trout—need several things from a waterway to survive. Cold, clean, slow-moving freshwater. Shade provided by redwoods and other trees growing along the banks. Submerged logs, boulders, and other structures for shelter. And plentiful bugs to eat. Historically, the Prairie Creek floodplain had all of those in abundance.

Industrial logging changed that.

Decades of timber harvesting loosened the hills around Prairie Creek, sending tons of soil rushing into the waterway. Over time, sediment accumulated in the flats, forcing the creek into a deep, narrow channel, straightening its natural curves, and cutting it off from its floodplain. So when heavy rain fell, instead of spreading gently across the valley, the creek turned into a high-speed chute—like a water cannon blasting through the landscape.

Living in a water cannon makes things pretty difficult for baby coho. In fast-moving water, they spend huge amounts of energy to avoid being flushed away. As a result, the fish that survive begin their adult lives smaller and weaker, easy prey once they reach the sea.

But upstream of ‘O Rew, Prairie Creek flows through the park’s pristine, protected boundaries. It’s a salmon paradise, providing critical rearing habitat for North Coast coho. Every fish born in this upstream haven must pass through the ‘O Rew section of the creek during a crucial period in its life cyle. Here was a clear opportunity to give each young salmon a better chance to thrive.

This made the floodplain an important and ideal restoration candidate. The major obstacle: the former mill site.

A new course for Prairie Creek

The restoration process was anything but easy. What made it possible was a shared vision among Save the Redwoods and its partners—especially those with local aquatic expertise—that the delicate ecological balance at ‘O Rew could be restored.

That transformation began with moving a whole lot of dirt and concrete. Most of the heavy lifting was done by the Yurok Tribe Construction Corporation. They peeled away 20 acres of asphalt and concrete and then dug up 250,000 cubic yards of accumulated sediment, which they used to build up and stabilize other project areas.

Next, they moved Prairie Creek itself.

But first, crews had to figure out how to keep the creek’s waters moving. Several times, they routed the creek through a large pipe system so it could continue flowing during construction. Meanwhile, they built new sections of the creek, including an 800-foot bend that moved the stream away from Highway 101 and connected it to a 2-acre pond, creating the kind of habitat growing coho can park themselves in for a while. Fatten up a bit.

Moving the creek meant moving its residents too. Each time the channel was shifted, crews gently scooped up thousands of fish and other creatures and kept them safe in holding pools. Once flow was restored, those fish, which included lamprey species along with salmon and trout, were released into their new home.

If you build it, the fish will come

Because unchecked sediment and roads covered parts of the floodplain, it was impossible to recreate exactly. “We used some historical information to approximate what the habitat would have been like,” says Mary Burke, CalTrout regional manager. And, because of the aquatic restoration expertise of local design, engineering, and compliance firms along with the Yurok Tribe’s construction expertise, the partnership was able to produce the conditions young coho need to grow healthy and strong.

Each time new sections of the creek were opened, crews would spot young salmon and trout swimming in the clear, cold water, finning against the soft currents. These fish are extraordinarily sensitive to their environment. Their quick return signals a promising future for the restored creek and its wildlife. A future the Yurok Tribe will continue to monitor and steward.

“When I look into the future of habitat restoration, I see this project setting up a strong precedent,” Burke says. “It shows that stewardship is essential for success. State and federal agencies need to recognize that—so future funding for projects like this supports ongoing, hands-on involvement for years. That’s the key.”

Ancestral lands back in Yurok hands

Barry McCovey is the director of the Yurok Tribal Fisheries Department. He lives on the Yurok Reservation, not far from ‘O Rew. For years, he’s watched the land change from a working lumber mill to a defunct mill site (the saws went quiet in 2009), and now to a verdant, natural wetland.

“The project turns back the clock a bit, getting us pretty close to what the stream was before there were extractive industries in that watershed,” McCovey says. “To see this property come full circle and make this incredible transformation has been amazing.”

In 2026, Save the Redwoods will transfer ‘O Rew to the Yurok Tribe. The site will serve as the southern gateway to Redwood National and State Parks and Yurok Country, featuring an expanded network of hiking trails and engaging interpretive exhibits highlighting the area’s iconic redwoods and Indigenous culture. All thanks to the Yurok Tribe’s stewardship, Save the Redwoods’ vision, and a collective partnership committed to restoring this special place.

“This will have such a tremendous impact on the millions of people who visit here,” Carter says. “The perspectives, the experiences that can be had by starting from a place of understanding Indigenous history and what true partnership in a region looks like.”

Instead of a broken-down mill site, ‘O Rew is now a place where both people and salmon can thrive together—as they did for millennia.

“When you think about what it means to be a Yurok person, there are a few pillars that hold that together,” McCovey says. “The river, our language, redwood trees, and salmon. They’re incredibly important. Not just for cultural, subsistence, and commercial value, but for our identity as Yurok people.”

The salmon will grow strong in Prairie Creek, move to the sea, then return home one day to spawn. As they’ve always done. And the Yurok Tribe will watch over ‘O Rew and its salmon. As they’ve always done.

5 Responses to “5 years of teamwork revives North Coast salmon haven”

Mary Lou Rosczyk

Even though I live in Southern California, the inspiring account of the restoration of the ‘O Rew property is the reason that I support the Save the Redwoods League.

Rachel Woods

This is great news about a great partnership. Thank you for enduring the challenges of this project to see it to fruition.

Bonnie Miller

Since relocating to Del Norte county, I would see this area while driving to Eureka. I wondered what the project was, and now, I know. Thank you, and keep up the great work!

Robert Threlkeld

I love what you folks do and I’m happy to donate to you. Keep up the good work!

BILL SCOBLE

Inspiring. Wonderful to see all the hard work come to fruition. For man and for wildlife. It CAN be done.