Coast Redwoods Facts

| FACT | WHERE | COMPARE |

|---|---|---|

| Tallest Tree: 380 feet | Redwood National and State Parks | As tall as a 37-story building |

| Widest Tree: 29.2 feet | Redwood National and State Parks | The length of 2 Volkswagen Beetles |

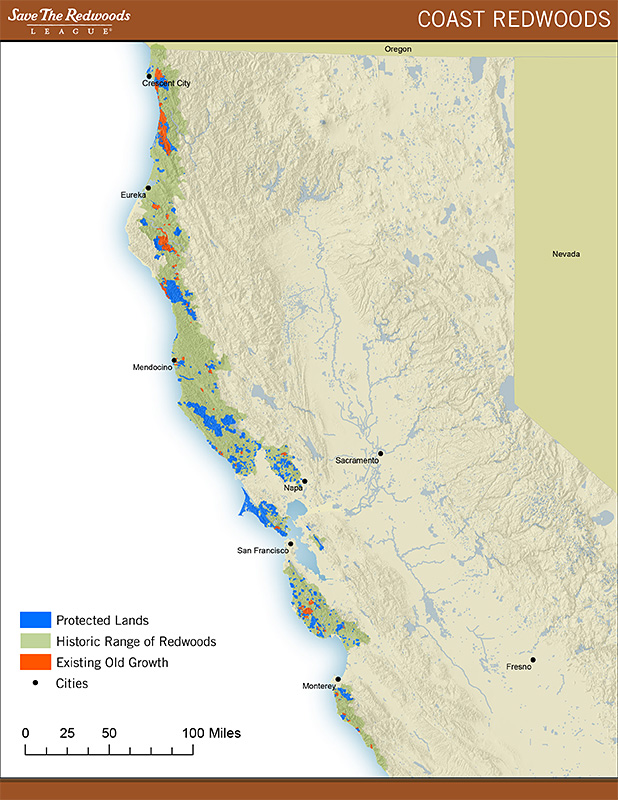

| Remaining old-growth forest: 110,000 acres (5% of original) | From southern Oregon to Central California | About size of San Jose |

| Total protected redwood forest: 382,000 acres (23% of their range) | From southern Oregon to Central California | The size of Houston |

| Privately owned redwood forest: 1.2 million acres (77% of their range) | From southern Oregon to Central California | The size of 4 Rio De Janeiros |

To learn more, visit our Redwood Forest Facts page.

About Coast Redwoods

The Tallest Trees In The World

Standing at the base of Earth’s tallest tree, the coast redwood, is one of life’s most humbling and amazing experiences. These California trees can reach higher than a 30-floor skyscraper (more than 320 feet), so high that the tops are out of sight.

Their trunks can grow more than 27 feet wide, about eight paces by an average adult person! Even more incredible: These trees can live for more than 2,000 years. Some coast redwoods living today were alive during the time of the Roman Empire.

History

Redwoods once grew throughout the Northern Hemisphere. The first redwood fossils date back more than 200 million years to the Jurassic period. Before commercial logging and clearing began in the 1850s, coast redwoods naturally occurred in an estimated 2 million acres (the size of three Rhode Islands) along California’s coast from south of Big Sur to just over the Oregon border. When gold was discovered in 1849, hundreds of thousands of people came to California, and redwoods were logged extensively to satisfy the explosive demand for lumber and resources. Today, only 5 percent of the original old-growth coast redwood forest remains, along a 450-mile coastal strip. Most of the coast redwood forest is now young. The largest surviving stands of ancient coast redwoods are found in Humboldt Redwoods State Park, Redwood National and State Parks and Big Basin Redwoods State Park.

The native people of California did not typically cut down coast redwoods, but used fallen trees to make planks for houses and hollowed out logs for canoes. The natives also regularly used common redwood forest plants. Read more about uses of redwood forest plants through our Redwood Forest Plant Guide.

Biology

The coast redwood is one of the world’s fastest-growing conifers, or cone-bearing trees. In contrast to the tree’s size, redwood cones are very small — only about an inch long. Each cone contains a few dozen tiny seeds: it would take well over 100,000 seeds to weigh a pound! In good conditions, redwood seedlings grow rapidly, sometimes more than a foot annually. Young trees also sprout from the base of their parent’s trunk, taking advantage of the energy and nutrient reserves contained within the established root system.

Frequent, naturally occurring fires play an important role in maintaining coast redwood forests because they rid the forest floor of combustible materials. Forest fires create space for redwood seedlings (and other plants) to grow. In contrast, decades of fire suppression practices usually result in the accumulation of dead plant material that may fuel intense, destructive fires.

Redwoods can usually survive natural forest fires because of their thick (up to 12 inches), protective bark. Redwoods get their name from the beautiful reddish hue of their bark. Redwood bark is soft, fibrous and rich in tannins (which help prevent insect damage). You can learn more about the impact of fire on our redwood and sequoia forests through our blog.

Where coast redwoods live, temperatures are moderate year-round. Heavy rains provide the trees with much-needed water during the winter months and dense summer fog contributing moisture to the forest during the dry summer months. Redwoods even create their own “rain” by capturing fog on their leaves. The coastal fog condenses on redwood needles creating water droplets. Some of the water is absorbed by the needles and some drips to the ground, providing water to the redwood forest understory. You can learn more about the relationship of redwood forest plants and fog through our research grants.

In recent years, scientists have discovered that life abounds in the canopy (the tops of old trees) and on the forest floor. Canopy research supported by Save the Redwoods League has revealed that many species can live in the redwood canopy, including worms, salamanders and plants such as Sitka spruce, ferns and huckleberry.

Learn more about these majestic trees and download the California’s Redwood State Parks brochure.

Conservation

Since 1918, Save the Redwoods League has been working to protect, restore and conserve our remaining redwood forests. We have helped protect redwood forests and surrounding land totaling more than 200,000 acres (about the size of New York City). Our conservation work depends on close partnerships with scientists, land managers, industries and other land conservation organizations. We’re the only organization with the type of comprehensive approach needed to ensure that forests that take one thousand years to grow will be here for another thousand years.

You can learn more about our conservation work by visiting our protect and restore pages.

Research

To help protect redwood forests, we must continue to study them. There is still much we do not know about these towering giants and their surrounding forests. Through our Research Grants Program we have learned that:

- Redwood forests are affected by the tree disease commonly known as “sudden oak death.” Sudden oak death kills tanoak trees, a redwood forest inhabitant. When tanoaks die, extra brush is created, increasing fire intensity by three to four times than those in forests not affected by the disease.

- Amphibian species are also affected by the destruction of old-growth forests. Researchers found fewer than half as many animals at a property containing young, very small, mostly second-growth trees than at adjacent parkland containing undisturbed forests.

- To increase the population of martens, which depend on old-growth forests for their home, researchers found that suitable marten habitat can be created by planting understory shrubs like rhododendron and evergreen huckleberry, strategically removing roads and installing “rest boxes” for the animals.

You can read more about League-funded research projects on our research grants page.

Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative

To meet the pressing need for research on how redwoods can survive sweeping environmental changes, the League and redwoods scientists launched the multiyear Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative. Our goal is to create a comprehensive climate adaptation strategy for the redwoods. These findings will help focus League efforts on where to protect and restore redwood forestland according to climate change forecasts.

Working on scales from leaves to landscapes, no other team of investigators in the world has the unique and complementary skills to conduct this integrated 10-year investigation of redwoods. The investigation includes a network of forest plots that can be monitored for more than 100 years. This program will yield data-based solutions to protect redwoods in a changing world. Read about our initial results on our Understanding Climate Change pages.

Visit the Redwoods

Check out our free resources that will help you plan your trips and learn more about the forests. You’ll find an interactive trip planning tool, redwood forest guides, events and a live webcam.

You Can Help

Today, it takes a community including private landowners, parks, local communities, scientists and our supporters to safeguard redwood forests. Together, we protect redwood forests from threats such as unsustainable development; restore the forests we have lost; and connect people to these towering wonders of nature. With your help, we can leave the forests — and the world — in a better place than we found them.