What it’s like to protect giant sequoias at immediate risk

With a flash of lightning, a fire ignites naturally near several giant sequoia groves in California’s Sierra Nevada. It’s early August and the overly dense vegetation surrounding some of the sequoias is dry and flammable. The threat of a high-intensity, tree-torching fire is real. So who do you call to help?

In the case of the August 2024 Coffee Pot Fire, wildland firefighters were the first responders called to the scene. But as the fire quickly expanded out from Coffeepot Canyon, on the edge of Sequoia National Park, technical experts were also mobilized to reduce adverse impacts to the park’s natural and cultural resources. These Resource Advisors, or READs, included archaeologists, a Tribal liaison, a wildlife biologist, and several giant sequoia experts. Among them was Linnea Hardlund, forest ecologist at Save the Redwoods League.

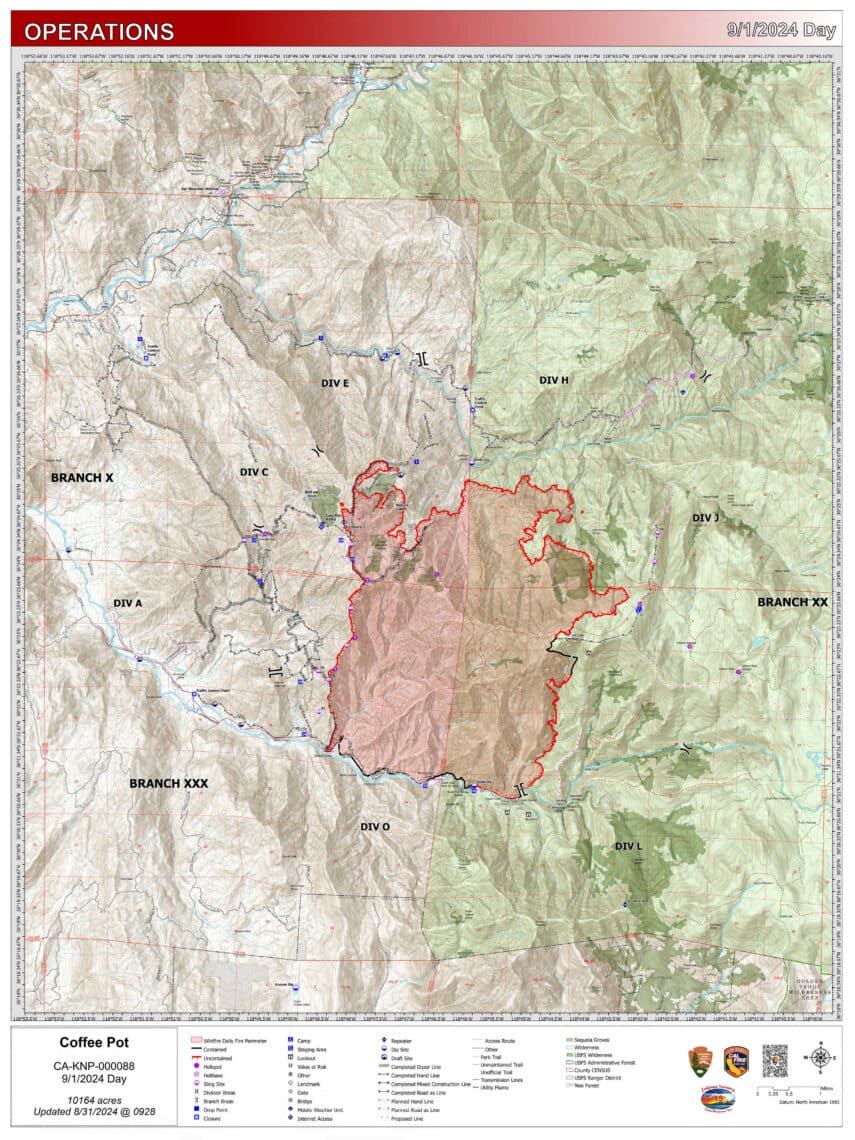

Arriving at the fire, Hardlund and other giant sequoia READs immediately met with fire and resource managers from the National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Their charge: to facilitate the rapid treatment of vulnerable sequoia groves ahead of the advancing fire. Says Hardlund, “We all stood around a table with a big map and discussed different grove management scenarios based on fuel loading, fire history, treatment history, topography, weather, and feasibility.”

Given the rugged landscape, access to the sequoia groves proved to be a key factor. In the accessible groves, the READs recommended rapid treatment by crews on the ground. For inaccessible sequoia groves, the READs recommended “aerial firing,” in which an experienced technician ignites small fires via helicopter or UAS (Unmanned Aircraft System) to encourage fire to burn downslope with less intensity.

Using fire to protect sequoia groves at risk of being torched may seem counterintuitive. But Hardlund explains that burning under favorable conditions—such as during cooler weather or at night, when temperatures drop and humidity rises—typically produces lower-intensity fire that can clear excess fuels without harming the ancient trees. Providing these recommendations was part of her duties as a Resource Advisor, along with identifying vulnerable trees and sensitive habitat to avoid as firefighters constructed fire lines.

Hardlund’s role also meant leading hand crews in several accessible sequoia groves. Crews cleared overly dense vegetation, removed ladder fuel and standing dead trees known as “snags,” and scraped the ground around the base of large sequoias to reduce excessive heat. For Hardlund and all the other resources on the Coffee Pot Fire line, it was two weeks of working 16-hour days.

Hardlund describes this sometimes-grueling work as exciting and rewarding. “It was a unique opportunity to apply my sequoia knowledge, prescribed burn experience, and fire qualifications,” she says. Hardlund first became qualified as a Resource Advisor in 2018, while working in Yosemite National Park on fire ecology and wildland fire crews. At the League, her role involves studying the health of giant sequoias and devising strategies for their conservation. Increasingly, that means assessing the impact of megafires, which have killed roughly 20 percent of mature sequoias since 2020. “My career has led me to become somewhat of a field expert on sequoia fire mortality.”

By mid-September, the Coffee Pot Fire was 90 percent contained, having burned more than 14,000 acres, including approximately 800 acres within sequoia groves. Hardlund and other READs took to the air to assess the fire’s impact in the groves via helicopter. She was buoyed by what she saw. Although not every mature sequoia survived, the impact was nothing like the devastation of the 2020 Castle Fire or the 2021 Windy Fire. “The Coffee Pot Fire was largely restorative for giant sequoia as it mostly burned at low and moderate severity within the groves,” says Hardlund.

Another success: the rapid mobilization of giant sequoia experts to the fire, and their cooperation across multiple agencies and NGOs. Hardlund sees this as a reflection of the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition (GSLC), which has united giant sequoia stewards in a shared mission to address existential threats to these magnificent trees. For three years now, members of the GSLC, including Save the Redwoods League, have worked to restore fire resilience to the sequoia groves after more than a century of fire suppression. Hardlund is proud of this collaboration and committed to her work protecting the giant sequoias in the face of megafires and other climate-driven threats. “This is all happening on our watch,” she says. “We have a responsibility to ensure that these trees endure.”

2 Responses to “League scientist plays frontline role on the Coffee Pot Fire ”

Vida Kenk

I wish I could share this article. I am a volunteer at Calaveras Big Trees State Park, which is just downhill from my home. We just did a big prescribed burn in the South Grove in November (over 1100 acres; the South Grove is 1300 acres total).

Paul

Thanks for an interesting note on helping our wonderful redwoods to survive a fire. And for showing us why it’s called the “Coffepot” fire.