New research follows reports of several dead monarchs with significant beetle infestations

Responding to reports that a native bark beetle may be contributing to the death of ancient giant sequoias that were thought to be incredibly insect resistant, Save the Redwoods League is embarking on a study to better understand this beetle and its potential threat to the giant trees.

Visitors to the Sierra Nevada in recent years have been stunned to see whole mountainsides full of brown, dead trees, mostly pines and firs. This extensive tree mortality was the result of a combination of bark beetles and drought. These beetles have evolved with the forest, where they have always preyed on weak trees, creating dead ‘snags’ that are important features of the forest. But the recent, severe drought has weakened the trees and made them much more susceptible. The extent of this devastation has been jaw-dropping: more than 129 million trees have been killed since 2016.

As this crisis was unfolding across the forests of the Sierra, one bright spot was the imperviousness of the giant sequoia to this type of threat. Its thick bark is rich with tannins that repel most pests, helping make them resistant to insect damage. That changed in 2018, when researchers identified several dead giant sequoia monarchs that had significant signs of beetle infestations (see Appendix A of this study). These dead monarchs were observed at the tail-end of the historic 2014-2016 drought and occurred in areas that had sustained recent low severity fires, where the trees were injured by the fire, but unlikely killed by fire damage alone. The hypothesis is that perhaps the combination of drought stress and fire injury weakened the trees enough for beetles to have a significant, and potentially lethal, impact. Ironically, this phenomena was concentrated in wetter areas, perhaps because the trees in these areas had the least extensive root systems prior to the drought. Once the severe drought hit, they may have had poor access to deeper, more reliable water. We still have a lot to learn about the degree to which the beetle is contributing to individual tree death.

To better understand this phenomena, the League worked with scientists from the United States Geological Survey and the National Park Service to develop a partnership with Dr. Seth Davis, a forest entomologist from Colorado State University. Together with the Yosemite Conservancy, the League is funding a study to better understand the basic biology of the western cedar bark beetle (WCBB), Phloeosinus punctatus. This beetle has long been known to occasionally feed on giant sequoia, as well as the incense cedars which occur alongside giant sequoia, but was never previously considered more than a minor nuisance to these ancient giants. By learning more about its basic biology, we can better understand its current role in monarch mortality, and evaluate potential forest management actions that could help curb its impact.

The goal of the research team is to learn more about the life history of the western cedar bark beetle and how it interacts with giant sequoia and incense cedar in the forest. This will include:

- Genetic barcoding of WCBB to determine if some of these beetles are unique a unique subset that specializes in giant sequoia;

- Developing integrated pest management methods, including chemical attractants, for WCBB control; and

- Investigating how activity of WCBB in giant sequoia and incense cedar may be related

Field research will take place in three groves in the Sierra Nevada, including Grant Grove and Giant Forest in Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks, and Mariposa Grove in Yosemite National Park.

Ultimately, we hope that this study will inform our efforts to manage giant sequoia forests, reduce the impacts of WCBB, and promote the long-term health of the giant sequoia.

Learn More

RCCI Forest Network

Learn about our research partnership studying the impact of climate change on the redwood forest.

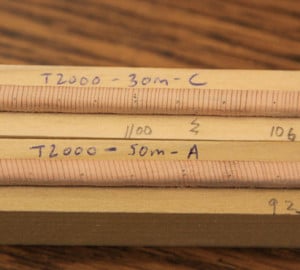

Decoding Tree Rings

Tree ring analysis provides critical information on tree ages and how redwoods throughout California respond to climate conditions. See the initial discoveries our scientists have made about the age of the oldest-known coast redwood.

Funding Critical Research

With help from our Initiative Advisors and Research Partners, the Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative will study the ecology of coast redwood and giant sequoia ecosystems in a changing world to inform forest conservation for the next 100 years and beyond.

The Leadership Funding Partners are helping lead the way to secure adequate funding for this important investigation. However, we still need your help.

Your donations are a critical part of the solution. Please make a gift today!