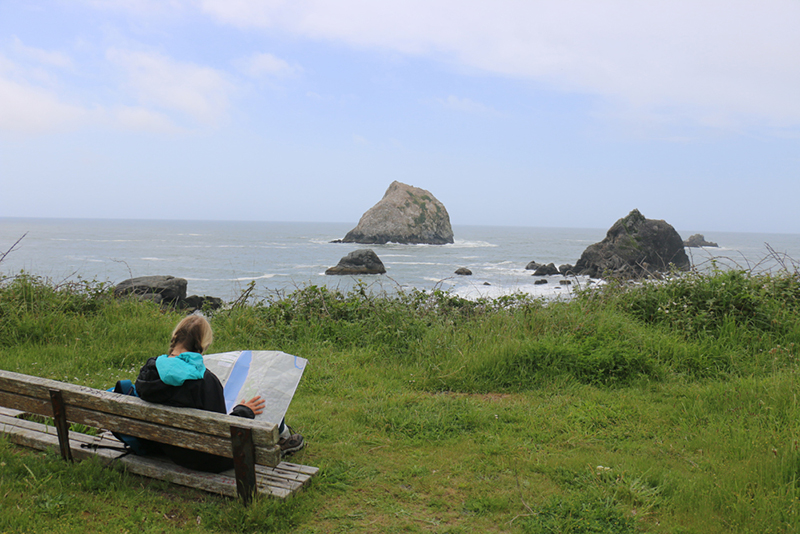

Hikers along the California Coastal Trail in Del Norte County have begun to mistake Morgan Visalli and Jocelyn Enevoldsen for twins. If you look past Visalli’s blonde hair and Enevoldsen’s dark brunette braids and pay attention to the color spectrum that radiates around them, you can see it too. They wear matching turquoise rain coats, handkerchiefs, and socks.

Hikers along the California Coastal Trail in Del Norte County have begun to mistake Morgan Visalli and Jocelyn Enevoldsen for twins. If you look past Visalli’s blonde hair and Enevoldsen’s dark brunette braids and pay attention to the color spectrum that radiates around them, you can see it too. They wear matching turquoise rain coats, handkerchiefs, and socks.

They planned their 1,230-mile thru-hike down the California Coastal Trail on aqua-, turquoise- and mint-colored sticky notes. They moved out of their apartments and packed their lives into teal and green backpacks. For three months, they will trek alongside deep blue and jade water while they hope for the occasional azure sky.

Even they say they’ve quickly merged into one turquoise-hued entity known as MoJo hikers. They carry one of everything, share a deep bond formed by parallel youths, and march toward common goals: to raise awareness of the California Coastal Trail, to build a connected community of coastal stewards, and to map and document the trail for the California Coastal Conservancy.

Today, forty years after the Coastal Act was signed, about half of the trail is completed and used by thousands of people every day. Though it was designated California’s Millennium Legacy Trail in 1999 by Governor Gray Davis, completing the trail still has its slough of problems.

“We had never even heard of the trail before we were involved [with Coast Walk California, the California Coastal Conservancy and Coastwalk],” said Visalli. “There are challenges designating funding in the state budget and getting local jurisdictions to build local parts of the trail. It’s even difficult to know exactly how much is finished and to post signage where it is.”

This month, two additional spans of the trail opened in Mendocino County. The first was the 2.3-mile Peter Douglas Trail in Shady Dell, adjacent to Sinkyone Wilderness State Park and owned by Save the Redwoods League. The League’s contribution to the trail makes the Lost Coast Trail an even 60 miles. The second to open recently was the 4.6-mile stretch of the Coastal Trail in Noyo Headlands State Park, just outside of Fort Bragg.

Walking out of the southern end of Redwoods National and State Parks, Visalli and Enevoldsen want this sort of trail development to become the norm.

“Up here in Northern California, where there’s more nature, more wild and open spaces, everyone values, respects and cares for the land,” said Visalli.

“The coastal environment is so dynamic that it takes a constant renewed set of eyes to know what’s going to be important for the coming years of climate change,” added Enevoldsen. “We have to be using natural buffers like wetlands for shore armoring and to conserve what’s left. Communities and organizations up here are doing just that to set a strong example of stewardship and conservation.”

The duo have deep roots in stewardship and conservation. Both are graduates of UC Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science on the tail end of California Sea Grant State Fellowships, and both have worked with the California Coastal Conservancy and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

But their responsibility to the coast is rooted more deeply than professional and academic interest. Both grew up along the coast, Visalli on Barnegat Island off the New Jersey shore and the U.S. Virgin Islands and Enevoldsen along the Ventura County coast. There, they fostered powerful connections with the ocean and entrenched their commitment to protect it.

“People in my life who have spent a good amount of time in nature seem the happiest, and I find that in myself too,” said Enevoldsen. “When I’m in nature I’m the happiest and the best version of myself.”

The pair are avid scuba divers, hikers and surfers. When Enevoldsen turns 28 on the trail, they plan to take a layover day and surf in San Onofre, Orange County.

Still, they could never be completely prepared for their 1,230-mile Coastal Trail journey. Along with the standard equipment for a journey of this magnitude, they packed cameras, cables, computers, and GPS. They carry the recording equipment they need to update maps, take photographs, interview locals and develop content for the Coastal Conservancy’s upcoming app, “Explore The Coast,” to be released in six months.

“It’s an epic adventure of self sustainability, it’s an adventure for a cause that we feel so strongly about: public access and stewardship,” said Visalli. “Peter Douglas [the late California Coastal Commission executive and Shady Dell trail namesake] said ‘The coast is never saved, it is always being saved.’ That’s some of the spirit we’re carrying with us along this journey.”

Those communities have been enthusiastic. In Crescent City they were welcomed by families, students, the Chamber of Commerce and a County Supervisor. Down the trail they have been invited into people’s homes for coffee, cookies and the luxury of fresh sheets.

There are more than 1,000 miles to go for Visalli and Enevoldsen. The challenges for first-time “thru-hikers” abound, from long days at a fast pace to equipment, weather and infrastructure complications along the incomplete portions of the trail. Being two women alone on the trail has concerned a few of their close friends and family, but the pair view it as one more challenge with one more goal.

“We’ve seen a lot more single male hikers, but for us this is all we know,” said Enevoldsen. “We want to encourage other women to get out there too and to show girls that they can totally do this, that it doesn’t have to be another male-dominated sport.”

For now they’re cheerful and say that this is the time of their lives. They’re keeping tight to their schedule and the communities are excited about stewardship and connecting the trail. But one of their finest moments happened when the two were alone, sacked-out and happy at the end of their first day. They dropped their packs and sat on the beach to watch the sun set over Del Norte County and the Pacific. Right off the shore a whale surfaced and made ripples that lapped along the coast.