Bob grinned as he confirmed to us that in fact, we would be crossing the bridge. “Weren’t you warned? It’s the only way across. Move slow, stay on the left, and you’ll be fine.” After Bob climbed onto the first plank, his dogs jumped past him and trotted fearlessly across the bridge. We followed and separated ourselves to ease the stress on the old cables and limit any swaying. The milky-emerald water of the Mattole River rushed below, overflowing from recent storms.

Bob grinned as he confirmed to us that in fact, we would be crossing the bridge. “Weren’t you warned? It’s the only way across. Move slow, stay on the left, and you’ll be fine.” After Bob climbed onto the first plank, his dogs jumped past him and trotted fearlessly across the bridge. We followed and separated ourselves to ease the stress on the old cables and limit any swaying. The milky-emerald water of the Mattole River rushed below, overflowing from recent storms.

Crossing the rickety bridge was a gateway to terrain that demanded grit and ingenuity, and the challenge seemed to symbolize the undertaking of ecological conservation in the region. Stepping from one plank to the next was carefully planned and tested, proceeding only when the wood felt secure. Some of the rotting planks were covered in moss and widely spaced, leaving little to focus on besides vertiginous open air. Others appeared fresh and recently tied to the cables, providing brief moments of relief and confidence to move forward. We were only visitors on this private property, advising Bob on plans to restore and protect sections of his land, addressing each concern step by step.

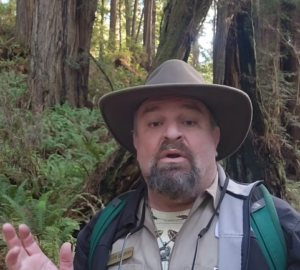

Save the Redwoods League holds a conservation easement on Bob’s 4,000-acre ranch, which is not accessible to the public, to help with the land’s stewardship and prevent the property from being broken into smaller parcels. This agreement is essential in an area where other large ranches have been subdivided into smaller farming operations. The cumulative effects of which have cleared thousands of acres of forestland, pressuring a fragile watershed and disturbing wildlife habitat and migration corridors. Some landowners, like Bob, wish to farm sustainably and earn a living in a way that supports a healthy environment but others do not share these values. Successful and complete protection of this landscape depends on our ability to identify and collaborate with willing landowners across property lines.

Bob’s ranch is also an important piece connecting the Corridor from the Redwoods to the Sea (external link). To the northeast is Humboldt Redwoods State Park, which includes the largest remaining old-growth redwood forest in the world. To the southwest are the Kings Range and Lost Coast that contain the longest stretch of undeveloped coastline in the continental United States. Maintaining a healthy corridor between these areas is vital for the movement and recovery of wildlife, including threatened mesocarnivores such as the Humboldt marten and Pacific fisher. In the past, community-led organizations have helped safeguard land within the Corridor, including neighboring BLM land around Gilham Butte. Under the leadership of the League, nine conservation easements have been acquired that add over 10,000 acres of protected land to the Corridor. The largest easement is Bob’s ranch, which continues to operate as a sustainable working landscape, providing an example of how to bridge the concerns of environmental protection with a rural economy.

Once across the old bridge, we uncovered a side-by-side vehicle, piled on and followed Bob’s dogs up steep slopes to the ridgeline above. Along the way, we passed through woodlands comprised of Oregon white oaks, draped in lichen and dripping in the rain. Small Douglas-firs were beginning to grow under the canopy and along the edge of the surrounding conifer forest, forming a tiny army of encroaching trees. Without careful stewardship, these Doug-firs could eventually overtop and out compete the oaks, eliminating these trees and with it, important habitat. Bob pointed out the effort to preserve the woodland.

Once across the old bridge, we uncovered a side-by-side vehicle, piled on and followed Bob’s dogs up steep slopes to the ridgeline above. Along the way, we passed through woodlands comprised of Oregon white oaks, draped in lichen and dripping in the rain. Small Douglas-firs were beginning to grow under the canopy and along the edge of the surrounding conifer forest, forming a tiny army of encroaching trees. Without careful stewardship, these Doug-firs could eventually overtop and out compete the oaks, eliminating these trees and with it, important habitat. Bob pointed out the effort to preserve the woodland.

“The fish and wildlife service has helped me do some work here, pilling the small trees to be burned and girdling the larger trees,” he told us.

Fifteen hundred feet above the river, the winds picked up, hurling raindrops that splashed against our flushed cheeks. More armies of tiny Doug-firs could be seen on the edge of the conifer forest, but this time they were gaining control of the prairie system that wrapped the ridgeline. At the end of the first prairie, the road disappeared into the forest. The entrance was dark and overcrowded with trees that contested for any remaining space, including the road.

An old-growth Doug-fir came into view that was charred from fires long ago, and we stopped to get a closer look. The tree had a giant branch that once stretched out into the prairie, but its stems now extended upward to reach the light penetrating through the thick forest. The in-growth not only created a dense, unhealthy forest but dead and broken woody debris posed a significant fire risk. In the event of a wildfire, the tinderbox would burn hot and out of control. It’s hard to imagine larger fire-resistant trees, like the old Doug-fir, surviving such an incident.

An old-growth Doug-fir came into view that was charred from fires long ago, and we stopped to get a closer look. The tree had a giant branch that once stretched out into the prairie, but its stems now extended upward to reach the light penetrating through the thick forest. The in-growth not only created a dense, unhealthy forest but dead and broken woody debris posed a significant fire risk. In the event of a wildfire, the tinderbox would burn hot and out of control. It’s hard to imagine larger fire-resistant trees, like the old Doug-fir, surviving such an incident.

The League is currently working with Bob to carry out a forest thinning restoration project in this area that would extend a 5.5-mile long fuel break, recover dwindling meadows, free up growing space to improve forest resiliency, and prevent catastrophic wildfires from spreading across the area. The thinning treatment can be described as a thin from below, where the smallest trees are cut first, and the dead branches on larger trees are limbed. The slash needs to be treated further by creating piles that are burned in the winter or chipping the cut material into mulch that decomposes faster.

We emerged out of the dense forest into a vast prairie that overlooked miles of the Mattole River. Fog swirled from the forest canopy across the river valley, and the view gently emphasized the remoteness of the rugged landscape. A small herd of cows guarded the road, and I noticed the freshly grazed grass. In the absence of a healthy and regular fire regime, Bob’s herds of cows and sheep made up one line of defense against conifer encroachment into the prairies. We discussed the possibility of setting controlled burns that could benefit the prairies, maintain the open oak woodlands, limit in-growth, and prevent catastrophic and high-intensity wildfires.

The road dropped elevation as we passed through a section of the forest that looked more like the late seral old-growth forests to the northeast. Over the years, this stand was carefully and selectively logged to provide income for Bob’s family. With prudent management the stand now looks vigorous, developing an intricate and layered canopy structure typically found in old-growth.

The road dropped elevation as we passed through a section of the forest that looked more like the late seral old-growth forests to the northeast. Over the years, this stand was carefully and selectively logged to provide income for Bob’s family. With prudent management the stand now looks vigorous, developing an intricate and layered canopy structure typically found in old-growth.

We reached the edge of the property line and looped back through to where we started. Before parting ways, Bob encouraged us to put together a new project proposal. As he has seen first-hand, the conifer forests, oak woodlands, and open prairies can continue to be resilient, productive, and diverse with the right action plan. He was looking forward to starting a new project with us.

While watching Bob drive through the hills with his canine companions leading the way, it was clear that he was proud of his land and deeply cared for its future. As we crossed back over the old, rickety bridge, swinging in the wind above the Mattole, we thought of the careful steps Bob took to tend to his land over the years, and of the meticulous stewardship we’d continue together.