How a maverick scientist helped restore burning in the sequoias and beyond

On a crisp fall day in 2025, nearly 90 people gathered in a meeting hall beneath the giant sequoias of Calaveras Big Trees State Park. Scientists, authors, and forestry experts took to the podium. They explored topics such as “pyro-silviculture” and enthused about the benefits of “putting fire on the ground.” Audience members leaned forward in their seats, eagerly taking in slides showing tall trees surrounded by low flames.

What may have looked, at times, like a Fire Addicts Anonymous meeting, was in fact a celebration of one man’s legacy: Harold Biswell, the pioneering ecologist who helped restore beneficial fire to California. At the dawn of the Smokey Bear era, Biswell dared to suggest that fire could be a force of both destruction and renewal. He argued that the policy of complete fire exclusion was only making the woods more flammable—and that careful, controlled burning could return overgrown forests to a healthier, more natural state.

This “renegade” stance earned Biswell public snubs and professional setbacks. But ultimately, his iconoclastic ideas prevailed. Though he clearly didn’t invent beneficial fire—Indigenous Tribes had practiced cultural burning in California for millennia—his pioneering use of prescribed fire indelibly shaped the health and safety of our forests and communities.

Opening his eyes to the power of fire

Born in 1905, Harold Biswell was a Missouri farm boy with a keen interest in science. After earning his Ph.D. in ecology, he headed to Georgia to conduct research for the U.S. Forest Service. The year was in 1942, and Biswell still held conventional beliefs about fire, writing that “At the time, I was new to burning and looked upon fire as the arch enemy of forests and forestry.”

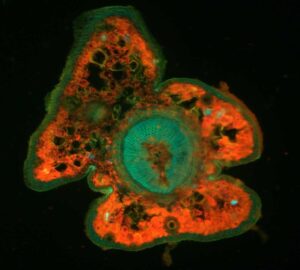

This perspective didn’t last long. In the Southeast’s pine forests, Biswell was introduced to the regional practice of understory burning. He observed firsthand how small, low-intensity fires could clear the forest of dead and overgrown vegetation, encourage native plant species, and improve wildlife habitat and the ecosystem’s overall health. Ever the scientist, he revised his theories: Unchecked wildfire remained the enemy, but controlled fire was now a valuable ally.

A not-so-warm welcome in California

In 1947, Biswell joined the faculty at UC Berkeley’s School of Forestry. At the time, California was a tough place to be a fire evangelist. Indigenous cultural burning, which had helped create open, park-like sequoia groves in the Sierra Nevada, had been banned outright in the state for nearly a century—part of a larger campaign of displacement and violence against Tribes. In 1924, California adopted a policy of complete fire exclusion.

Biswell’s initial research at Berkeley, which focused on grassland burning, was largely uncontroversial. But in 1951, he began testing understory burning in the ponderosa pine forests. Many faculty members saw the use of fire in forests as reckless or even dangerous—especially given the high value of timber to California’s growing economy. Although Biswell proved to be a cautious and methodical researcher, the faculty banned him from conducting any fire research at the university’s Blodgett Forest.

Biswell’s reception beyond campus was harsher still. Members of the park and fire-fighting communities mocked him with nicknames like “Harry the Torch” and “Burn ‘Em Up Biswell.” When he got up to speak at an event in Yosemite National Park, the park rangers reportedly stood en masse and walked out of the room.

National influence and the Leopold Report

But Harold Biswell never gave up. He found landowners willing to let him burn safely on their property and built a compelling body of evidence on the positive effects of controlled fire in forests. This work included early fire research in the giant sequoias at Whitaker’s Forest, a privately held property near Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks.

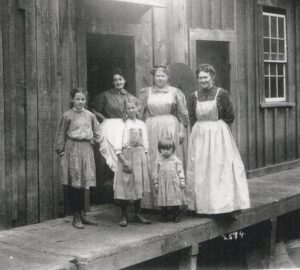

Just as important, Biswell shared his research and taught his techniques. Throughout his career, he regularly held field days that focused on prescribed fire demonstrations. A dapper figure in his porkpie hat, he would enthusiastically describe his methods to a circle of listeners that included students, members of the public, land managers, and fellow academics.

One of these early converts was A. Starker Leopold, a prominent wildlife ecologist and fellow Berkeley professor. Biswell’s ideas directly influenced the 1963 “Leopold Report,” a wildlife policy paper that urged national parks to bring fire back into their ecosystems. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Sequoia & Kings Canyon and Yosemite national parks launched their own prescribed burning programs. Biswell wasn’t credited at the time—his name remained controversial—but his ideas on fire had accelerated an important shift in national policy.

From Berkeley to the parks

Retiring from UC Berkeley in 1973, Biswell found a receptive burning partner in California State Parks. In 1975, he led the first prescribed burn at Calaveras Big Trees State Park, helping to catalyze an ongoing effort to restore beneficial fire across the park’s giant sequoia and mixed conifer forest. He also developed the agency’s first prescribed fire curricula and conducted controlled burns in parks around the state, including Big Basin Redwoods State Park.

Biswell passed away in 1992, but his legacy continues to grow. Many of the students, scientists, and land managers who attended his demonstration burns went on to become leaders in modern fire and forest management. Several were among those who gathered last fall for Harold Biswell Day at Calaveras Big Trees. Some spoke emotionally of Biswell’s courage and persistence. Others addressed the urgent need to expand prescribed fire programs in the face of increasingly destructive megafires. Decades after Biswell sounded the alarm, the state is still contending with the legacy of 100-plus years of fire exclusion.

Answering Biswell’s call

A month after Harold Biswell Day, Governor Newsom signed an executive order calling for the rapid deployment of beneficial fire to reduce wildfire risk across California. “We’ve made tangible progress but much more is needed,” said Newsom in a statement. “I’m tasking state agencies to pull all the levers and gear up for using ‘good fire’ this year to help protect communities and restore healthy landscapes.”

The order underscores the degree to which Biswell’s pioneering techniques are now widely accepted practice—and the remaining challenge of applying them at scale. For Save the Redwoods League and our partners, answering that challenge means building landscape-scale alliances, training a skilled workforce, and using scientific studies and Traditional Ecological Knowledge to inform and improve forest stewardship. When timing and conditions are right, it means conducting burns across the redwood range, from the giant sequoia groves of Alder Creek to the coast redwood forests of Harold Richardson Redwood Reserve.

It means that in a warming, more wildfire-prone West, “good fire” isn’t just a concept to celebrate beneath the big trees. It’s a powerful tool, to be wielded with purpose.