Meet the researchers exploring this delicate relationship—and how climate change is disrupting the balance

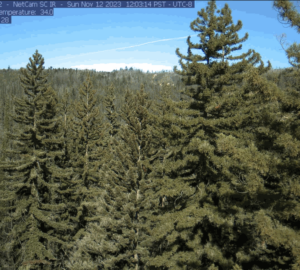

A gentle mist drifts silently through the redwoods, softening shadows and imparting a damp chill to the air. Moisture drips from branches and ferns, emanating an earthy, pine-like aroma. The scene of fog shrouding a redwood forest evokes a sense of mystery and awe, its ephemeral beauty casting a filmic, dreamlike quality to the landscape.

Perhaps even more captivating is the hidden, interwoven relationship between fog and coast redwoods.

From May through October, coastal fog forms over the Pacific Ocean when cold ocean water—churned up by wind, ocean currents, and the Earth’s rotation in a process called upwelling—meets warm, moist air. The contrast in temperatures causes the water vapor in the air to condense into tiny, suspended microdroplets, or fog. Sucked ashore by inland valley heat, fog stretches its cool hand over the coast redwood forest, where tree canopies capture it like nets. When fog condenses on redwood leaves, some of the water is absorbed. The rest drips down to the ground, where the roots of the redwood trees drink it in.

Fog is coastal California’s natural air conditioner and a crucial source of water for redwoods during the warmer, drier summer months. Research by UC Berkeley professor Todd Dawson, one of the world’s foremost experts on fog and redwoods, shows that summer fog can provide 30 percent or more of the annual water intake for coast redwoods, helping them grow to more than 300 feet tall.

But today, climate change is threatening this relationship between redwood forests and fog. Warming oceans combined with warmer and drier air are disrupting the conditions for the formation of coastal fog—and thus depriving many redwoods of much-needed moisture.

A 2010 study coauthored by Dawson found that fog declined by 33 percent between 1951 and 2008. According to Dawson, ongoing research indicates that fog declined another 7 percent between 2010 and 2023.

“I think all of the evidence points to the fact that we are going to see changes in the redwood forest.”

—Todd Dawson, UC Berkeley professor

This warmer, drier future has implications for the entire forest. “When redwoods capture that fog and create fog drip, they’re not just watering themselves,” says Laura Lalemand, senior scientist at Save the Redwoods League. “They’re providing moisture for all these other plants and animals in the coast redwood ecosystem.”

Lalemand has no doubt that climate change will affect redwood forests. The question is how to best help these precious ecosystems survive. “Although there is still uncertainty about where and when we will experience increases or decreases in fog and rain, these shifts potentially pose a big threat,” says Lalemand. “It’s something that everyone in redwood conservation and research would like to understand better.”

That is one of the many reasons why Save the Redwoods League awarded grants to several scientists studying the relationship between the redwood forest and fog. Research funded by the 2024 Redwood Research Grants will help us better understand how coast redwoods might adapt to shifting fog patterns in the future and how we can support them. But first the scientists must venture into the forest to find out precisely how much water these giants are getting from fog.

What tree cores can reveal

It’s a sunny Friday morning in late September and UC Berkeley PhD student Rebecca Choi and research assistant Isabel Donovan are hunting for coast redwoods at Point Reyes National Seashore. Using the iNaturalist app for leads, they hike up the Randall Trail through a stand of mostly Douglas-firs and California bay laurels. Finally, they spot a young coast redwood alongside the trail.

Donovan puts an increment borer, resembling a large, skinny corkscrew, against the tree at chest height and begins turning it clockwise, drilling a tiny hole 4 millimeters in diameter into the trunk. The sound of metal against wood reverberates through the forest like a winding clock punctuated by a knock. R-r-r-r-it, bok!R-r-r-r-it, bok!

Donovan extracts a small sample of the tree’s core (this does not harm the tree), which Choi seals inside a plastic tube. Almost immediately, the air inside steams up due to condensation. Even though it’s nearing the end of the dry season, the inside of the tree is surprisingly moist—and that may be partially because of fog.

Choi, in collaboration with Professor Dawson, is studying how coast redwoods use fog, rainfall, and groundwater in different ratios across their range—a project that is one of four funded through the League’s 2024 research grants. In addition to the tree core, Choi also takes samples of nearby well water and rainwater, as well as fog collected via a net at a nearby field station. Back at the lab, Choi will identify the samples based on their isotopic composition and then determine how much water the tree is absorbing from each source. She will conduct similar research at other sites throughout the year.

Through this research, Choi and Dawson hope to gain insight into how the warming climate is changing the coast redwoods’ dependency on fog versus other water sources.

Dawson suspects that coast redwoods will start to use less fog water, particularly at the southern and eastern edges of their range, where it is drier. This change could diminish tree growth. He noted that at the southern end of the range, where it’s getting warmer and there’s less fog, researchers have already observed some tree crowns starting to thin. “They weren’t dying, but they definitely were not as healthy as we had seen,” says Dawson.

Researchers take a closer look at leaves

Just how crucial fog is to helping redwoods grow is the subject of research by another pair of grantees, Professors George Koch and Andrew Richardson at Northern Arizona University, who are measuring tree growth on foggy versus clear days. Their hypothesis is that coast redwoods produce less new wood during days with little or no fog.

The other two funded projects are looking into exactly how these massive trees receive all the water they need to thrive. One answer may lie in their leaves. While most plants get all the water and nutrients they need directly from the soil, redwoods face the challenge of being so tall. “There are physiological complications associated with slurping water up 300-plus feet,” says Rebecca Hewitt, an assistant professor at Amherst College. As a result, coast redwoods have evolved adaptations, such as the ability to absorb water directly through their leaves and bark.

Leaf traits turn out to be great predictors of how much water redwoods can absorb. Alana Chin, an assistant professor at Cal Poly Humboldt, is studying how several key traits vary in different climates inside and outside the natural coast redwood range. “As the climate is changing, which direction are these traits shifting?” asks Chin. “Are they becoming better able to use fog water, or less?” The study’s results may prove valuable in selecting nursery stock for restoration projects and predicting where the trees will thrive in the future.

A redwood’s microbiome may also influence how much water its leaves absorb. Hewitt and Lucy Kerhoulas, an associate professor at Cal Poly Humboldt, are exploring how the microscopic fungal communities on redwood leaves may enhance a tree’s ability to absorb fog and other water sources, as well as marine-derived nitrogen, an important nutrient. “They might actually act as wicks,” says Hewitt of the fungal threads that have been documented sticking out of the leaves’ pores.

This work could potentially help efforts to reduce the effects of decreased precipitation. If the research team is “able to identify certain fungi that are real winners,” says Kerhoulas, forest managers could introduce these microbes to redwood trees to improve their water intake.

As much as redwoods soak up the fog, the trees also amplify fog’s presence in the forests. “Our data shows quite clearly that when trees and continuous redwood forests are present on the landscape, the prevailing conditions are foggier,” says Dawson. That’s because the presence of coast redwoods creates cooler, still air. And fog dripping from the trees increases humidity, allowing fog to linger longer. Without redwood forests, Dawson explains, the landscape would be warmer and thus less foggy. And, in less scientific terms, perhaps less magical.

Although there are still many unknowns about the redwoods’ future during a time of climate change, “there are definitely alarm bells,” says Dawson. “I think all of the evidence points to the fact that we are going to see changes in the redwood forest.” While he doesn’t think coast redwoods will disappear from California, their range may shrink. “I fear that in a century from now, the southern and eastern ranges will probably contract … as we march into a warmer, drier future.”

The hope remains that as these League-funded studies uncover more about the dynamic relationship between redwoods and fog, we might be able to better track and prepare these forests for an uncertain future. “Our goal is to gain insight into how redwoods will respond to continued climate change and its impact on fog patterns,” says Lalemand. “We want to respond appropriately and do whatever we can to continue to safeguard these incredible trees and the unique ecosystems they help create.”

Redwood Research Grantees

Since 1999, Save the Redwoods League has awarded grants annually to researchers who seek to deepen our understanding of how to protect redwood forests in a changing environment. For our 2024 awards, we invited researchers to submit proposals on the theme “Redwoods and Water.” In total, the League provided the final four projects with $188,000 in grant funding to advance essential redwoods research.

Todd Dawson, PhD, and PhD student Rebecca Choi

UC Berkeley

What water sources do coast redwoods tap throughout the year? To answer that question, this research team is using stable isotope analyses of water from the trees and the environment to identify and compare water use from fog, rainfall, and groundwater sources.

George Koch, PhD, and Andrew Richardson, PhD

Northern Arizona University

These scientists are examining the relationship between daily and seasonal redwood growth and nighttime fog availability. Their research will help us better understand how changes in fog may impact coast redwood forests, starting at the scale of an individual tree.

Alana Chin, PhD

Cal Poly Humboldt

Building on her team’s previous research on how coast redwoods uptake fog, Chin is studying how three key leaf traits—surface wax and the size and density of the stomata (the minute pores in the epidermis of the leaf)—affect a redwood tree’s capacity to absorb fog moisture. Chin will also examine how this capacity changes with variations in the climate.

Rebecca Hewitt, PhD

Amherst College

Lucy Kerhoulas, PhD

Cal Poly Humboldt

Hewitt and Kerhoulas are assessing how the microbiome on the surface and inside of leaves influences the absorption of water and marine-derived nitrogen from fog. They are also exploring how the microbiome communities on leaves vary throughout redwood forests, based on the individual tree, tree species, and location in the canopy.

This feature appears in the beautiful printed edition of Redwoods magazine, a showcase of redwoods conservation stories by leading scientists and writers, as well as breathtaking photos, and ways you can help the forest. Only a selection of these stories are available online.

Join our thousands of members today for only $25, and you’ll get future editions of our Redwoods magazine.