The League and partners advance a bold vision for Indigenous stewardship and public access at Redwood National and State Parks

On a blustery morning last March, fog hung over the redwood covered hills surrounding ‘O Rew, a culturally significant place to the Yurok people. A mountain of ripped-up asphalt provided a stark reminder that this property just outside Orick, California, once the site of a redwood lumber mill, was not always a place of hope.

But on that morning, the site was celebrated as a place of healing and renewal. Dozens of people gathered, near the southern entrance to Redwood National and State Parks, to sign an unprecedented agreement–one that might revolutionize how prized natural lands are stewarded.

Four partners stood around a folding table, wide smiles on their faces: Sam Hodder, president and CEO of Save the Redwoods League; Steven Mietz, Redwood National Park superintendent; Victor Bjelajac, superintendent of California State Parks’ North Coast Redwoods District; and Joseph James, Yurok Tribe chairman.

James tilted his head toward the sky, and said, “It’s an historical moment. Today we are signing an agreement in the heart of Yurok ancestral territory to transfer 125 acres to the tribe.”

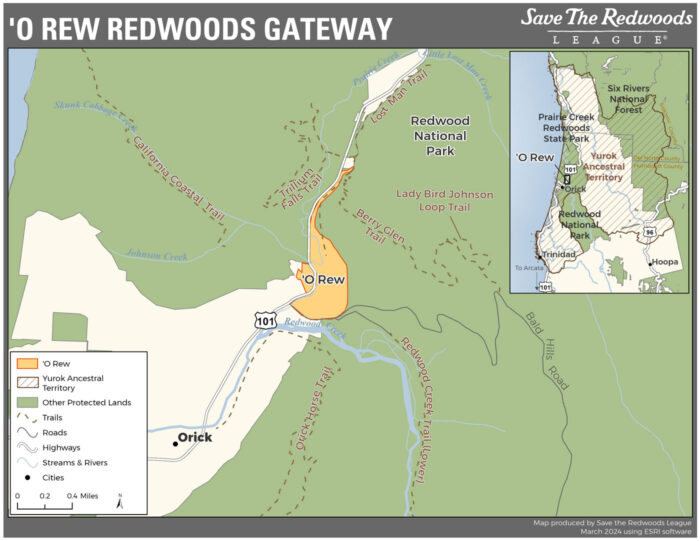

The agreement, a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), describes the four partner organizations’ shared vision for long-term co-management of ‘O Rew as a gateway for the millions of visitors who experience the spectacular ancient groves of Redwood National and State Parks annually. Across the country, national and state parks own land that Indigenous tribes support and even manage, but the ‘O Rew Redwoods Gateway will be the first co-management model whereby the National Park Service and California State Parks will support visitation and stewardship on land owned by a tribe. The partners’ bold vision is to fully revive the site’s vital ecosystem and create an inspiring, welcoming visitor gateway to Redwood National and State Parks, featuring an expanded network of hiking trails, engaging exhibits, and a traditional Yurok village for cultural activities and interpretation.

At the ceremony, Hodder explained that the agreement will advance a new vision to convey the gateway of the parks to the Yurok Tribe with perpetual conservation and public access.

Jessica Carter, the League’s director of parks and public engagement and ‘O Rew project manager, beamed. The League had been working on this project for over a decade. “We are starting this vision from a place of strength.”

A tiny green frog leapt into Prairie Creek as James spoke. “We are healing the Earth here, healing our village, and healing us as people,” James said. “We signed an MOU, but it is so much bigger than that. We are providing an example of what a land back partnership looks like for conservation throughout Indian country. Land back doesn’t happen overnight. You got to roll up your sleeves and work as stewards of this land.”

A HISTORY OF YUROK STEWARDSHIP

‘O Rew is a story of restoring an ancestral connection. Long before loggers, Gold Rush settlers, and Spanish explorers claimed redwood land, the Yurok people stewarded a vast swath of the Northern California coast. At one time, over 50 Yurok villages stretched up the Pacific coast from Arcata to southern Oregon, and inland along the Trinity and Klamath Rivers. These were once vibrant communities of fishermen, artisans, and medicine people.

When outsiders first arrived in Northern California’s redwood country, they saw these giant redwoods, beautiful streams and rivers, the open prairies, and there was this notion that it was nature, and it was untouched,” explained Rosie Clayburn, Yurok tribal heritage preservation officer and cultural resources director. “What they failed to notice is that those lands were always managed by the Yurok people. Hunting, fishing, and traditional burns are [our] management tools.”

An example of that stewarded natural world was ‘O Rew, situated at the confluence of Prairie Creek and Redwood Creek, just 3 miles from the Pacific coast. Trails connected communities with each other, as well as the ocean, river tributaries, and old-growth redwood groves. Prairie Creek and its floodplain provided a safe habitat for juvenile salmon to mature before heading out to sea.

In the mid-1800s, the land was taken from the Yurok people by colonists seeking to extract gold and redwood timber. In 1955, ‘O Rew became a prolific mill for turning old-growth redwoods into lumber–a process that gravely damaged the redwood forest and the floodplain habitat. Soon, juvenile salmon no longer populated the degraded Prairie Creek.

Tribal council member Phillip Williams worked at the mill in the 1990s. “When I was younger,” Williams said, “this was a dirty, noisy place. We didn’t have any connection of ownership to the land, even though my DNA is part of this land.”

After the mill closed in 2009, Save the Redwoods League purchased the property and began seeking partners for an ambitious plan to restore ‘O Rew. The League began collaborating with the Yurok Tribe, National Park Service, California State Parks, and many other key partners. In 2021, the team kicked off a five-year, $23 million restoration of Prairie Creek, led by aquatic restoration experts from California Trout and the Yurok Tribe, with the California State Coastal Conservancy as the funding lead. In the first three years, Indigenous crews removed 10 football fields worth of asphalt from their ancestral lands and restored a heavily degraded section of the creek and surrounding floodplain.

At the signing event, Hodder surveyed the netting spread along Prairie Creek to protect recently planted trees and shrubs taking root. “Look at the remarkable complexity of this land: giant fern mats in the remnant old growth trees, thousands of critters living in the restored creek, the salmon have come back, the elk are browsing. And as we are just downstream from where Redwoods Rising is restoring the forest of the upper watershed, we are bearing witness to the healing of the landscape.”

‘O Rew is among many projects in which the League collaborates with California’s Indigenous peoples. As the original stewards of redwood forests with a deep commitment to protecting and caring for these lands, tribes are valued partners in the League’s mission to protect, restore, and connect people to treasured places. In Mendocino County, the League transferred ownership of properties to the Intertribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council. With the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians, Save the Redwoods is developing a public access plan for the League’s Harold Richardson Redwoods Reserve in Sonoma County. And in the Sierra Nevada, the League is working with the Tule River Indian Tribe of California to restore giant sequoia groves.

A BLUEPRINT FOR A BRIGHTER FUTURE

Dreaming up and implementing a massive restoration project and committing to an unprecedented co-management agreement between four organizations is just the start for ‘O Rew. Work is underway on adding visitor amenities, interpretive exhibits about the partners’ conservation efforts, and several new hiking trails, including a connection to the popular Lady Bird Johnson Grove in Redwood National Park. The goal is to make this an inviting place for the visiting public to engage with the redwoods and Indigenous culture—where the Yurok Tribe will have the chance to shape the narrative about their past, present and future.

“Our vision,” offered Clayburn, waving a hand over the construction site, “has always been to create a hub for Redwood National and State Parks to welcome visitors to a Yurok village with plank houses and a sweat lodge. [We want to provide] safe elk viewing, interpretation of the restoration work, trails, and a place where tribal members come together. We will be using our [traditional Yurok land] management skills to help rebuild what was here.”

Innovation like this will take time and effort. The MOU sets clear goals for each partner to ensure the transfer process occurs. Mietz said that he has committed to helping partners navigate the process of collaborating with a massive federal organization like the National Park Service.

Armando Quintero, director of California State Parks, said the historic agreement provides a pathway for the addition of Indigenous lands to the suite of values employed in co-managing and protecting Redwood National and State Parks lands for the enjoyment of public and Indigenous peoples in the region. “This agreement further strengthens California State Parks’ relationship with the Yurok Tribe,” he said, “and we welcome the opportunity to forge additional actions that support Indigenous land management with state, federal, and nonprofit resources.”

Williams added, “We are starting to heal a festering cut for the Yurok people. Past leaders paved the way for us, and now we are just closing the deal. Now, with the return of these lands, we are being recognized for what we bring to the table: environmental conservation and stewardship. This is a blueprint for the parks systems and Indigenous communities. We’re restoring hope and making the future brighter together.”

—Michele Bigley

This feature appears in the beautiful printed edition of Redwoods magazine, a showcase of redwoods conservation stories by leading scientists and writers, as well as breathtaking photos, and ways you can help the forest. Only a selection of these stories are available online.

Join our thousands of members today for only $25, and you’ll get future editions of our Redwoods magazine.