Trees resprout from ancient buds and use decades-old carbon reserves

Few things embody resilience like California’s redwood forests. The bright lime green sprouts that emerged from the trees’ charred trunks in the weeks after the extreme 2020 CZU Lightning Complex Fire is just one example of redwoods’ ability to endure.

In a new multiyear study, funded by the League and published in Nature, a team of researchers observed unique adaptations that helped Big Basin old-growth redwood trees recover after the fires. Ancient buds that were dormant under the bark for centuries and decades-old carbon reserves are driving the prolific coast redwood tree regrowth, a discovery recently announced by and (NAU).

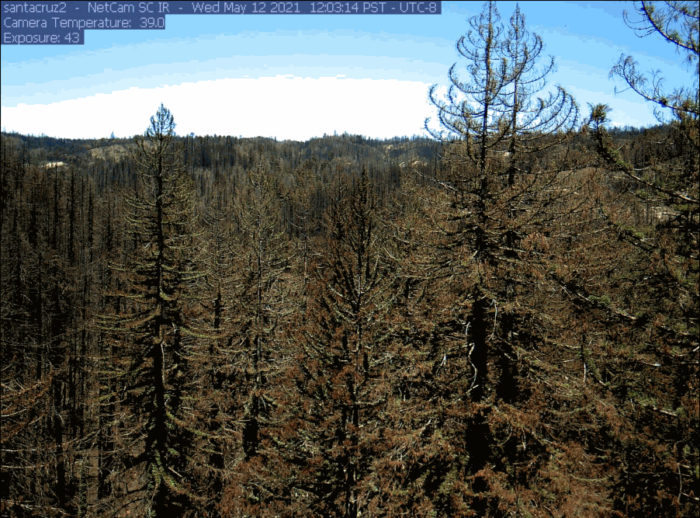

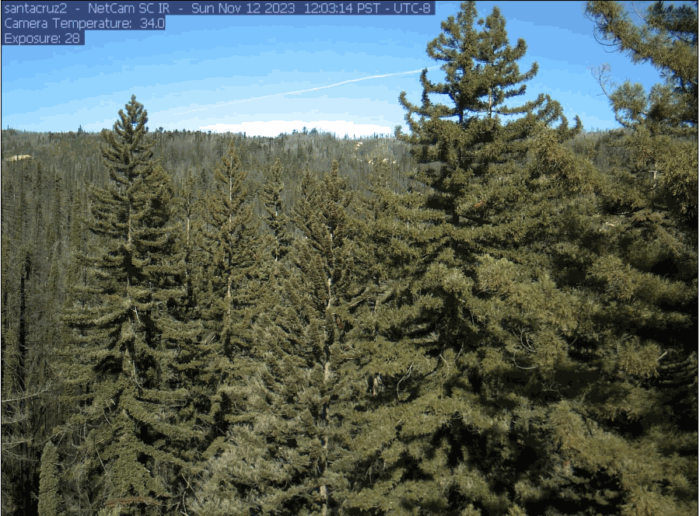

A time lapse shows redwood growth at Big Basin Redwoods State Park after the 2020 CZU Lightning Complex fires. PhenoCam Network, Phenocam.nau.edu and Mostafa Javadian, NAU

“Some of the results of this study suggest many of the redwoods at Big Basin were actually well prepared for this fire event,” said Drew Peltier, biologist and assistant professor at University of Nevada, Las Vegas (formerly at NAU). “Coast redwoods are extremely fire adapted and perhaps unusual in that they resprout after disturbances like fire. We were amazed to discover how they actually do that physiologically.”

“The CZU fire consumed all of the leaves on some of the tallest and oldest trees in the world, yet many are recovering,” said George Koch, professor of biological sciences at NAU. “Redwoods’ scientific name is ‘sempervirens,’ which means ever-flourishing. It’s very satisfying to have learned a bit more about how this remarkable species lives up to its name.”

The research team collected samples of small redwood tree sprouts at Big Basin following the CZU wildfire. Using a mini carbon dating system (MICADAS) at NAU—a first-of-its-kind tool in the United States at an academic institution—the team measured the number of radiocarbon atoms in the samples to determine the age of carbon reserves used to grow new leaves.

They identified that the carbon reserves the trees used to produce the sprouts were more than old. They also found that many burned old-growth redwood trees resprouted quickly following the fire, and that these sprouts emerged from buds that had been dormant under the trees’ bark for hundreds of years. Direct use of old stored carbon has rarely been documented and never before in such large, old trees. Some old-growth trees at Big Basin are more than 1,500 years old.

“This fascinating research reveals how coast redwoods have been able to adapt and survive for millennia by drawing on carbon they’ve stored for decades to give them new life,” said Joanna Nelson, PhD, League director of science and conservation planning. “These discoveries underscore why we have to protect the last remaining old-growth redwood trees, use best forest management practices and continue to restore younger second-growth forests—so they’ll have the capacity for resilience to future wildfires and other effects of climate change.”

Important work to improve forest resilience includes removing abundant standing dead trees and other combustible vegetation that the CZU blaze left behind. Such material could fuel another devastating wildfire, one that the ancient trees may not endure.

This feature appears in the beautiful printed edition of Redwoods magazine, a showcase of redwoods conservation stories by leading scientists and writers, as well as breathtaking photos, and ways you can help the forest. Only a selection of these stories are available online.

Join our thousands of members today for only $25, and you’ll get future editions of our Redwoods magazine.

One Response to “New discovery shows how redwoods regrow after extreme fires”

Ragbhir Singh

Today I visited Muir Woods. I am surprised to see fresh burn marks on the trunks of many old trees in the park. Would like to know more about the reasons of these burn marks. Is there a chance that the trees are intentionally burnt, to cause their death.