A holiday song to celebrate the redwoods and their amazing gifts to us

Imagine a small child, eagerly unwrapping a holiday package—and discovering the toy of their dreams. That wide-eyed wonder. That giddy excitement. It’s how many of us at Save the Redwoods League feel when we step into a redwood forest. Like someone just gave us the best present in the world.

So this season, we’re singing the praises of the redwood forest. Not just the big trees (don’t get us started on how much we love the big trees), but the creatures furry and feathered. The plants beautiful and bizarre. All the quirky participants in an ecosystem that hums in harmony.

And so, with a nod to that interminable holiday tune, we bring you “The 12 Days of Redwoods” (with full lyrics at the end)!

On the 1st of December the redwoods gave to me … a murrelet in an ancient tree!

A fish-eating seabird related to puffins? That’s probably the last thing you’d expect in a redwood forest. But marbled murrelets prefer to nest on the broad, mossy branches of old-growth coast redwoods—and will fly up to 50 miles inland from the Pacific Ocean to reach these prime sites.

The loss of old-growth redwood habitat has landed these birds squarely on California’s endangered species list. Also problematic: Marbled murrelets put all their eggs in one basket. Or rather, they typically lay only a single egg each breeding season—a big gamble, given how much Stellar’s jays enjoy murrelet eggs. Research funded by the League shows that reducing the density of jay populations through programs like the Crumb Clean Campaign can lessen the threat to marbled murrelets.

On the 2nd of December the redwoods gave to me … two spotted owls!

If there’s an avian icon of the old-growth redwoods, it’s the northern spotted owl. These dark-eyed beauties might be difficult to…well, spot. But if you’re ever in a redwood forest around dusk, listen closely for their four-note call—a “dash, dot-dot, dash” series of hoots.

The 1990 designation of these owls as a threatened species kicked off a heated controversy and brought increased attention to redwoods conservation. While habitat loss continues, northern spotted owls are increasingly threatened by barred owls, which are encroaching from the eastern United States. To tell the two species apart: Spotted owls have patterns of white ovals on their breast, whereas barred owls have dark streaks.

On the 3rd of December the redwoods gave to me … three black bears!

Bears are known for their big appetites, but did you know they nosh on redwoods? California’s native black bears strip bark from young redwoods to get at the sugar-rich cambium, a thin layer of living cells that produces wood. Great for a hungry bear…not so good for the redwood tree.

Black bears also make their dens inside redwoods, often in fire-carved cavities called basal hollows or goose pens. Though these dens are comfy, bears in California seldom hibernate through the entire winter, thanks to moderate temps and a year-round supply of vegetation.

On the 4th of December the redwoods gave to me … four hummingbirds!

Rufous hummingbirds are the bad boys (and girls) of the redwoods, known for their aggressive, “Are you talkin’ to me?” attitude. It doesn’t matter if they’re confronting a much larger hummingbird. Mess with the territorial rufous and you get the horns.

These tiny spitfires pass through California’s coast redwood forests en route to Alaska from Mexico—a spring migration of nearly 4,000 miles. Adjusting for size, this three-inch hummingbird makes one of the longest journeys in the avian world. It’s amazing that such a tiny bird can fly so far with such a big chip on its shoulder.

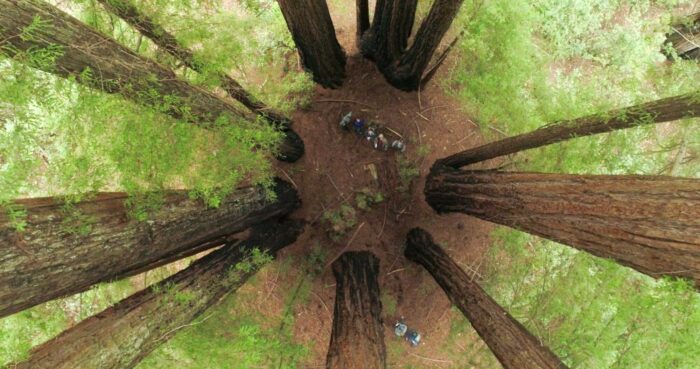

On the 5th of December the redwoods gave to me … FIVE FAIRY RINGS!

Are redwood fairy rings caused by A) magic B) aliens, or C) a natural process? Spoiler: It’s C. When a coast redwood is cut down or falls, new sprouts appear around the base of the stump, often in a near-perfect circle. These sprouts eventually grow into trees, the stump rots away, and—presto!—you’ve got a ring of redwoods around a mysterious clearing.

Logic suggests that each tree in this circle of life would be a clone of its deceased “parent.” But scientists have discovered that 10% of the redwoods in a fairy ring are genetically distinct from the rest. This diversity appears to be due to genetic mutations, pollinated seeds from the redwood’s seed cones, or interloping sprouts from neighboring trees.

Note that redwood fairy rings are distinct from mushroom fairy rings, which form when a spreading underground fungus sprouts a circle of mushrooms. Legend says these mushroom rings are caused by fairies, elves, or witches dancing in a circle.

On the 6th of December the redwoods gave to me … six ferns unfurling!

Ferns rule the redwoods. They blanket the forest floor, feather the sides of fallen logs, and fearlessly flourish a hundred feet in the air. Yep, these epiphytes grow high on the branches of coast redwoods, creating dense mats that shelter insects and even salamanders.

Coast redwood ferns species come in countless varieties. There’s the hearty western sword fern and the delicate California maidenhair, the cliff-hugging five-finger fern and the branch-covering leather leaf fern. The deer fern and the lady fern. Not to mention the sweet-tasting licorice fern and the fun-to-say California polypody.

Some ferns are evergreen, others are deciduous, but they all reproduce via “sori.” You know, those mysterious dots on the undersides of ferns? Each one contains clusters of sporangia, which burst open and release tiny fern spores by the thousands.

On the 7th of December the redwoods gave to me … seven slugs a-sliming!

Banana slugs are all about slime. Lacking a shell or karate skills for self-defense, they secrete a thick, sticky mucus that numbs the mouths of predators. It also prevents dehydration and helps the slugs traverse the redwood forest. You can imagine them as tiny slo-mo surfers, riding their own slime wave.

Bright-yellow banana slugs may have earned the entire Ariolimax genus its fruit-forward moniker. But banana slug species also come in more subdued shades of tan and green, and even spotted versions. A slug’s color can also shift with its diet, which can include live plants, fallen leaves, fungus, and carrion—but happily not redwoods.

On the 8th of December the redwoods gave to me … eight salmon spawning!

Chinook and coho salmon spend most of their life in the ocean. But it seems they never forget the redwood-shaded streams of their youth. Come spawning season, they migrate to their birthplaces, turning red to attract a mate. The males also develop a hooked snout, which the females, bless them, manage to overlook.

Adult salmon native to the redwoods—like the coho and Chinook—die after spawning. But there’s a silver lining: Redwoods and other plants receive vital nutrients from the salmon as they decompose. It’s a fish-fueled feedback loop, with the revived redwoods cooling salmon streams, slowing sediment erosion, and creating calm, deep pools for the salmon to chillax in.

On the 9th of December, the redwoods gave to me … nine bats a-sleeping!

Many bat species dwell in the redwood forests year-round, roosting in fire-carved hollows in tree trunks or sheltering in cracks in the redwood’s thick bark. Other bats migrate through these forests seasonally, including the hoary bat, whose white-tipped fur resembles flocking on a holiday tree.

The bats found in California’s redwoods are insectivores, meaning they dine exclusively on insects. If you camp in the redwood forest and aren’t tormented by flying pests, you might have bats to thank: According to Bat Conservation International, a small bat such as the little brown myotis can catch up to 1,000 small insects an hour, including mosquitoes.

On the 10th of December, the redwoods gave to me …10 squirrels a-leaping!

Bats are the only true flying mammals … but don’t tell that to a flying squirrel! These daring devils glide through the redwood canopy by splaying out their limbs, which are connected by a membrane called a patagium. Imagine a fur-covered hang-glider and you’ve got the gist of it.

In 2017 a distinct species called the Humboldt’s flying squirrel was discovered in the coast redwood range. These squirrels have impeccable taste in fungus, eating fragrant, above-ground truffles and their spores. When spotted owls eat the flying squirrels and later spit out the remains in owl pellets, the truffles get distributed around the forest. Smart, truffles. Smart.

On the 11th of December the redwoods gave to me … 11 mushrooms sporing!

From the pancake-colored “redwood rooter” to the poisonous red-and-white “fly agaric” of fairytale fame, mushrooms in the redwoods are just the tip of the fungus iceberg—a visual clue to an entire fungal world below ground. The so-called “Wood Wide Web” formed by mycorrhizal fungi and their thread-like mycelium connect the trees and plants of the forest, allowing them to share nutrients and find old classmates on Facebook.

Come reproduction time, many fungi send fruiting bodies (a.k.a. mushrooms) to the surface to release spores from gills—the beautiful, paper-thin ribbing on the underside of a mushroom’s cap. A single mushroom can produce billions of spores each day.

On the 12th of December the redwoods gave to me … 12 condors soaring!

With their jaw-dropping 9-foot wingspans, California condors seem made to soar above the world’s tallest trees. Happily, they have recently returned to the redwoods of Northern California. In 2022, the Yurok Tribe and Redwoods National and State Parks released eight young condors in Yurok ancestral lands—the species’ first redwoods appearance in over a century. In November 2023, three more California condors, called “prey-go-neesh” in the Yurok language, were released into the winged cohort.

These big birds seem to love the oversized dimensions of old-growth redwoods. They perch high in the canopy on broad branches, often in dead standing trees known as snags. In four or five years, when the young condors reach sexual maturity, the birds will likely roost in the redwoods’ spacious fire-carved cavities. And then, fingers crossed, so-ugly-they’re cut baby condors!

Ready to put “The 12 Days of Redwoods” together?

On the 12th of December, the redwoods gave to me…

12 condors soaring

11 mushrooms sporing

10 squirrels a-leaping

9 bats a-sleeping

8 salmon spawning

7 slugs a-sliming

6 ferns unfurling

5 FAIRY RINGS

4 hummingbirds

3 black bears

2 spotted owls

and a murrelet in an ancient tree!

5 Responses to ““12 Days of Redwoods” a sing-along for forest fans”

Ezequiel

Live this! Plan to translate in Spanish for the grandkids! Merry Christmas! Feliz Navidad!!

Paul Cooley

Lovely, and LOL funny. Thanks.

Sam Hodder

So great!

Leslie Peterson

totally enjoyed your 12 days in the Redwoods “song”, Kristina! Very clever!

JWest

What a fun way to review the gems of the redwoods.