In the space of just over a year, we’ve lost up to 20% of the world’s oldest, largest giant sequoia

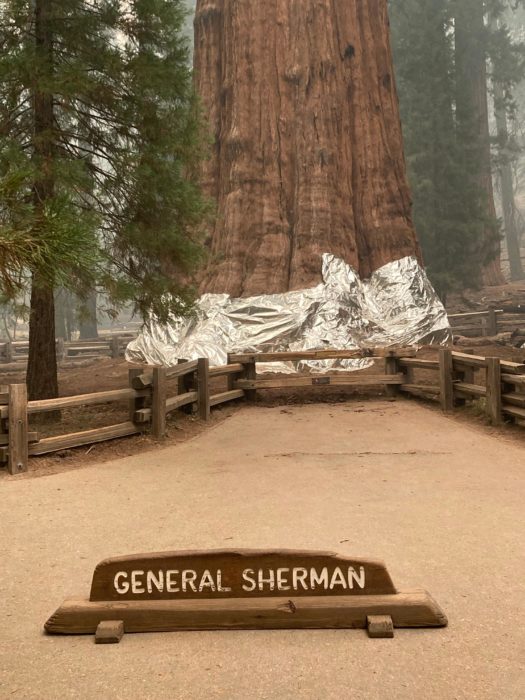

When photos of the world’s largest tree wrapped in foil-like material to protect it from oncoming wildfire went viral in September, people around the world quickly grasped something that others have perhaps been slow to understand: our treasured giant sequoia are facing an existential danger.

Thankfully, the General Sherman Tree and other renowned giant sequoia in Giant Forest grove were spared the worst effects of the KNP Complex fire, which as of this writing has burned more than 88,000 acres in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Park and Sequoia National Forest. This fire, and the Windy Fire to the south, have burned in at least 28 giant sequoia groves.

This year’s wildfires in the giant sequoia groves arrived on the heels of 2020’s SQF Complex/Castle Fire that researchers believe killed as many as 10,000 of the oldest, largest giant sequoia, perhaps 14% of these monarchs. Early estimates from the National Park Service and the Nature Conservancy from the KNP Complex/Windy fires show that up to 3,637 sequoias over four feet in diameter were killed or will die within the next three to five years. Added to the 2020 loss, it means that we may have lost nearly 20% of these incredible treasures in a 14-month span.

By the numbers: with an estimate of 10-14% loss in 2020, of all the giant sequoia on the planet, and an additional 3-5% estimated loss in 2021, we get to a worst-case scenario of 19%, nearly 20%. These analyses and estimates may be undercounting our losses…only field inventory will tell us the full story, and we will have to wait till next year for 2020 results.

Giant sequoia grow naturally in only 73 small groves over about 48,000 acres, which is less than half the size of Bakersfield. Unlike coast redwoods that resprout from burnt trunks or roots, when giant sequoia lose their crowns to fire, they die. And losing a tree that is a thousand or more years old, two thousand years, three thousand years… is a tragedy.

This is an emergency. If we were in the process of losing 20% of the Grand Canyon —or the Library of Congress, for that matter—we would expect people in positions of power to spring into action. We shouldn’t expect anything less with our beloved giant sequoia.

Giant sequoia have thrived alongside wildfire in Sierra Nevada for millennia. In fact, fire helps the great trees reproduce by releasing seeds from their cones. But for decades, well-intentioned land managers have suppressed the Sierra’s normal wildfire cycles, allowing unnatural overgrowth of shrubs and smaller trees. This fuel, combined with unprecedented dryness and weather patterns associated with climate change, is feeding severe wildfire that is overwhelming the defenses of the giant sequoia.

Another concerning aspect of the severe fires we’ve seen in recent years is that not only are they killing the monarch trees, but they’re burning so hot that they are wiping out seedlings and cones. If wildfire kills the mature trees, the cones with seeds, and the seedlings, there is no way for sequoia forest to recover and regenerate on its own. The League encountered this on our own Alder Creek property, which burned in 2020. We’re experimenting with replanting hillsides that once held giant sequoia forest, but won’t again unless we help them.

In 2017, a few dozen monarch giant sequoia perished from the Pier Fire in Black Mountain Grove, and researchers had never seen anything like it. That loss feels almost quaint compared to the thousands upon thousands that we’re losing now.

The factors that ultimately saved the General Sherman Tree, within the Giant Forest, hold the key to how we can save the surviving trees: the Giant Forest has benefitted from decades of prescribed fire as fuel reduction, a kind of stewardship that mimics the natural cycle of low-intensity fire that these forests historically saw. Unfortunately, not all of the groves hit by the KNP Complex or Windy Fire had the benefit of these treatments.

The practice of prescribed burning is unequivocally supported by both current Western science understanding and the traditional cultural knowledge and science of Indigenous peoples. For millennia, Native Americans stewarded these forests well and wisely, and they continue to steward these forests, despite violent interruption. The Tule River Tribe, a sovereign nation, is one of our partners in the coalition mentioned below, and they share our concern for the future of the big trees.

Indeed, we need to bring all stewardship practices to bear if we are to save these forests. We must tend them with consistent, stand-to-landscape-scale work. We must engage selective thinning, understory burning – prescribed fire, and cultural burning led by Indigenous practitioners – and other fuel-reduction and risk-reduction mechanisms. And it must all happen now and on an ongoing basis, before next year’s wildfires, and the next, and the next.

Treating these forests may be expensive, but just a fraction of the billions taxpayers have spent fighting these wildfires, the fear and loss involved in homes burning, and the sweat and risk that our firefighters spend. And the money is there. California has allocated more than $1 billion for forest management and wildfire prevention in this year’s budget, and even more could be available from federal economic recovery and infrastructure funding.

Funding isn’t the only factor. We also need to align policy and permitting around the goal of saving the giant sequoia, and we need a trained conservation workforce that can do the necessary work quickly, skillfully, and at scale. Recently, a group of government agencies, tribes, and nonprofit organizations joined to form the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition to raise public awareness about this crisis, build scientific research on wildfire and climate change, and take our shared knowledge directly into action to protect giant-sequoia forests.

It is vital that this collaborative effort turns into action on the ground, and fast. And for that to happen we need the full weight of conservation communities and lawmakers to quickly coalesce around shared goals and priorities.

We’re losing the giant sequoia forest in real time, right before our eyes. If we do nothing, within our lifetimes these great forests could be reduced to a handful of examples in museum-like parks and a few others planted in people’s front yards.

— Garrison Frost contributed to this article.

3 Responses to “An emergency in the giant sequoia forest”

Fred M. Cain

I realize that I’m almost certainly being overly optimistic and perhaps just a bit unrealistic, but I’m hoping and praying that these numbers might appear worse than what they really are.

I suspect, but cannot be sure, that at least a few trees that look for all the world to be dead might not be and recover. And I’m sure that a number of trees that are not dead yet but expected to die might also recover. How many, I have no idea. But one can at least hope.

The Sequoias have lived in those mountains for thousands of years and it’s difficult for me to believe that something like this hasn’t happened before in the distant past.

It’s possible and perhaps likely that Nature could mimic our misguided fire suppression. A long series of unusually wet years or even decades could allow a large buildup of fuels to accumulate. Then, a couple of drought years and an unfortunate lightning strike could’ve resulted in a similar kind of fire that we’ve seen today. Do I know this to be fact? No. But it seems logical.

It’s a no-brainer, really, that we need to thin forests and conduct prescribed burns. Everyone knows this including our officials. But the sad fact is it’s not happening or at least it’s not happening fast enough.

Part of the blame, I suspect, lies on the shoulders of Congress. They tend to keep the U.S. Forest Service, The Bureau of Land Management, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the National Park Service on a starvation budget. Hopefully this is now beginning to change.

Regards,

Fred M. Cain,

Topeka, IN

paul riley

did controlled burns help the trees. Who were the fire fighters who fought the fires that burned groves?

Jeremy McCabe

Some have money to offer. For others, what can we do to help?