New studies underscore the need for active restoration in burned and unburned groves

In August of 2020, the Castle Fire swept through the Board Camp Grove, a small, remote stand of giant sequoias at the southern end of Kings Canyon National Park. The fire burned through the crowns of many trees and left a charred landscape in its wake. Nearly every sequoia died. Four years later, few seedlings have sprouted to renew the grove.

Two new comprehensive research studies published by the USGS Western Ecological Research Center discuss the drastically low number of seedlings found in sequoia groves in the wake of recent mega-fires. Their findings: inadequate natural seedling recovery and high tree mortality rates create a substantial risk of losing portions of sequoia groves.

This research is helping members of the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition, including Save the Redwoods League, to better understand how giant sequoias regenerate in the wake of extreme fires—and what type of management actions to take in response.

Sequoias unprepared for modern mega-fires

Historically, giant sequoia groves experienced frequent wildfires that burned mostly at low to moderate intensity. The species adapted to not only survive these fires, but to use fire to their advantage.

“Giant sequoias are a pioneer species; they colonize after a disturbance using lots and lots of tiny seeds,” says Nate Stephenson, scientist emeritus at USGS Western Ecological Research Center.

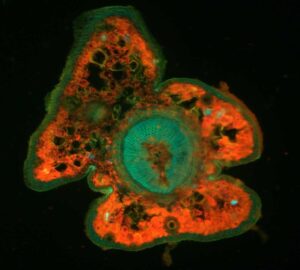

Heat from the fire coaxes open giant sequoia cones, which rain thousands of seeds onto the forest floor. These seedlings sprout in “hot spots”—patches of bare, fluffy soil where all the vegetation and litter on the forest floor has burned away. While only a small fraction of the sequoia seedling ultimately survive, it’s enough to ensure the continuance of the grove.

But thanks to a century-long policy of fire suppression, “the majority of giant sequoia groves haven’t seen fire in a long time,” says David Soderberg, ecologist at USGS Western Ecological Research Center. “There’s so much fuel built up on the ground that when fires hit, they have these drastic effects.”

“The parent trees are gone”

In one of the studies, researchers analyzed data from sampling plots in giant sequoia groves that had been treated with prescribed fires. These mimic the moderate intensity fires that the groves experienced for millennia.

Average seedling densities were calculated one, two, and five years following the prescribed burns. The results followed a pattern typical to groves that burn naturally: A burst of germination immediately after the fire, followed by much lower rates of sprouting in subsequent years.

However, Board Camp Grove and three other groves that burned at high intensity in 2020 and 2021 told a vastly different story.

“In areas where most or all giant sequoia were killed, the parent trees are gone,” Stephenson explains. “You have these large areas where you’ve lost the seed source and lost parent trees that could offer seed in the future.”

When giant sequoia crowns scorch rather than burn, they can still contribute seeds. But when the entire crown burns, the cones are incinerated, either on the tree or on the ground after they drop. Researchers found that groves that burned at the highest intensity suffered the greatest mortality. Far fewer seedlings sprouted and survived in the wake of these fires compared to the prescribed burn plots.

Drought and warming temperatures could be making the situation worse, says Soderberg.

“We’re having some of the hottest and driest summers that we’ve seen in recent history,” says Soderberg. “Are enough seeds falling, but the conditions are too hot and too dry for regeneration to be what’s been seen in the past?”

Prescribed burns key to sequoia survival

Researchers also found that devastation from extreme wildfires was not spread equally. In general, areas fared better in the high-intensity fires if they had recently experienced lower intensity fires, whether prescribed or natural.

For example, when the KNP Complex Fire entered an untreated portion of the Redwood Mountain Grove from the south, it burned hot through the canopy, killing many mature giant sequoias. By comparison, when the fire encountered forest that had been treated with prescribed fire, it dropped to the ground and crawled underneath the trees. Most giant sequoias in this part of the grove survived.

“It was a good example of the value of reintroducing fire to giant sequoia groves to prepare them for these kinds of wildfires,” says Stephenson. “If they’ve had prescribed fire within last 15 years or so, they’re going to do really well during a high-severity wildfire.”

Research helps stewards make science-informed decisions

In the last two years, the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition has treated more than 14,000 acres with thinning and prescribed fire and planted more than 542,000 native trees in burned areas, including the Board Camp Grove.

Unfortunately, many giant sequoia groves remain at risk, including some in remote wilderness areas.

Findings from the USGS will help coalition partners to prioritize unburned groves for restoration work and burned groves for planting nursery-grown seedlings.

“A lot of the data we’re collecting now will be used to assess risk for groves that we haven’t surveyed yet and that haven’t seen wildfire in a long time,” says Soderberg. “What we’re trying to do is give managers what they need to make science-informed and risk-informed decisions.”

By looking at how sequoia mortality and regeneration are impacted by fire severity, as well as by vegetation density, elevation, and other factors, researchers can forecast which other groves might be most vulnerable. They will “ground truth” their forecasts by physically visiting these groves.

This new research will help sequoia advocates and grove managers to give these magnificent trees the best chance to thrive in a changing climate.

This feature appears in the beautiful printed edition of Redwoods magazine, a showcase of redwoods conservation stories by leading scientists and writers, as well as breathtaking photos, and ways you can help the forest. Only a selection of these stories are available online.

Join our thousands of members today for only $25, and you’ll get future editions of our Redwoods magazine.

4 Responses to “Can the giant sequoias recover on their own?”

Tim Sweet

Good article, author seems to understand the interelatedness of the landscape. It’s a dynamic fluid process

Griff Griffith

Fascinating. I love what these studies are teaching us. Thanks for the interpretation, Juliet.

Stephen A Johnson

Are volunteers needed to plant seeds/seedlings in sequoia groves?

Ryland Bacorn

Yes, they can, and will recover if we stop interfering with the natural processes that have happened for eons before mankind stepped in. End fire suppression.