Shaandiin Cedar ventured into the naturalized coast redwood forest of New Zealand

Today is day 310 in Aotearoa, land of the long white cloud.

Eleven months ago, my partner and I said goodbye to Oakland, California, trading our small apartment for a tiny house on wheels where we work remotely and explore the two large Pacific islands that comprise New Zealand.

As we pull into our campsite for the night, I can smell the sulfuric geothermal feature next to the campground. This hotspring is one of many in the Rotorua region. We make a quick dinner and prepare for a full day in the Whakarewarewa Forest—home to the Tokorangi coast redwoods nestled among the park’s native bush. I fall asleep to the sound of rain on our metal roof, thinking about my countless walks beneath the redwoods of East Oakland, always finding peace away from the noise and hustle of the Bay Area metro machine.

Being a Guest on Indigenous Land

Growing up, the high desert mountains and evergreen forests of Northeastern Arizona were my playground. Dry sage air, large vistas, and tall pine trees are home to me. As a Diné (Navajo) woman, I know that this land is sacred, celebrated, and enshrined in the language, culture, and identity of my ancestors. There, I am a steward of the land and a gracious host to visitors.

The Indigenous people of New Zealand are the Māori—the original Polynesian stewards of New Zealand. They are our hosts now, teachers who are eager to share their stories, wisdom, and food. We now must be gracious guests on their sacred land.

I am 7,334 miles from home, but I don’t feel alone. I see the faces of my own family members in the brown faces of Māori men and women. From a historical and socioeconomic perspective, the Māori and Diné share several things in common. We value kinship and have built our intrinsic relationship to land into cultural teachings, songs, and oral histories. We value humor as a form of playfulness and as a coping mechanism. We’ve endured the dispossession of our lands by the British and still feel colonization’s lasting impacts on our people. Educational access, health issues, lack of economic opportunity, and loss of culture and language are challenges the Māori face and that I find eerily similar to those experienced by my own people.

Yet we are extremely resilient, building modern lives in a world vastly different from the traditional ones our elders knew.

A Walk in New Zealand’s Redwoods

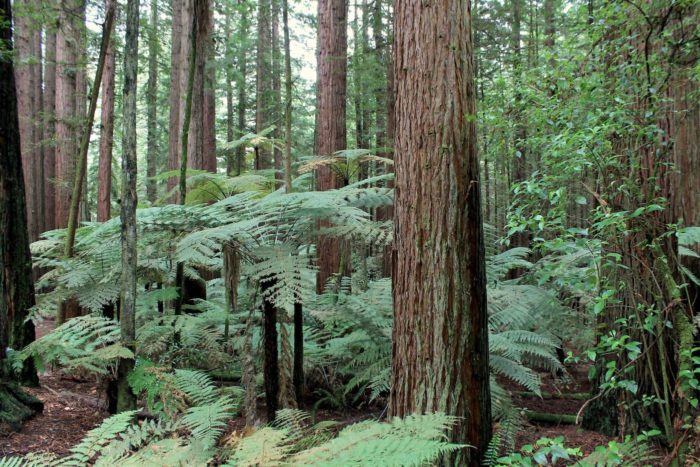

The California coast redwoods of Tokorangi forest are naturalized, meaning that the redwoods planted here in 1901 are not native to New Zealand but have survived and reproduced on their own, blending with the native forest. After planting 170 species for forestry viability testing, only a few species survived, including the California coast redwood. After years of monitoring the trees’ growth and potential for timber, the redwoods in this area were left to grow in peace.

As I walk past the first outcropping of redwoods at the beginning of the Redwood Memorial Grove track, I immediately notice the rich humidity from last night’s rain. My partner and I don’t get very far down the track, stopping every few steps to look up and breathe in the familiar scent of damp evergreen bark and humus—a comforting smell that brings me back to California.

The climate in the North Island is typically subtropical, giving life to a predominantly mossy, jungly beech forest landscape. It’s in this environment that the redwoods thrive—finding a way, though, to coexist with some of the native undergrowth. The 67-foot mamaku (black tree fern), whekī (rough tree fern), and ponga (silver tree fern)—New Zealand’s national emblem—grow in abundance underneath the redwoods, creating a unique visual aesthetic of bright leafy greens against shaggy rust reds.

The soundtrack of forests across New Zealand is especially entertaining to those like me who are accustomed to crows, finches, and ravens. The Tokorangi forest is no exception. The treetops are filled with the beautiful melodies of songbirds, songs consisting of a complicated mix of sharp staccato pitches and complementing notes. Before the arrival of the first European settlers, New Zealand was truly the land of the bird. With no mammalian or reptilian predators on either island, bird species like the kiwi, takahe, tui, fantail, and weka flourished and still play an important role in maintaining the ecological balance of the forest’s seed distribution and fertilization cycles.

The trail leads us across a geothermal site—a little bog with crystal clear blue waters that entomb its fallen plant victims in a white mineral casing.

The largest redwood in Whakarewarewa is 236 feet tall and 5.5 feet wide, living side-by-side with its adopted tree kin.

The Teachings of the Forests

In 2009, the protected land on which the Whakarewarewa Forest and Tokorangi Forest reside returned to Māori ownership as part of honoring the Treaty of Waitangi, the historic settlement with the Māori and British Crown that was signed in 1840. The geothermally rich area and native forests are culturally significant to the Māori, as is another giant tree native to New Zealand, the kauri.

Like the redwood, the kauri tree is one of the largest and longest-lived trees in the world. Ancient Māori iwis (tribes) named the largest kauri tree Tāne Mahuta, estimated to be more than 2,000 years old, its gray, flaking trunk measuring 50 feet around. Kauri trees are known to the Māori people as Te Whakaruruhau—the great protectors of the forest—referring to the many different plant and animal species that shelter in its branches and at its base.

The Māori believe that they are a people meant to be stewards of the ocean and forest. Their oral stories and songs about Tāne (the protector of the forest), Ranginui (the sky father), and Papatūānuku (the earth mother) remind me of the fundamental teachings of the Diné: that we must recognize and maintain the balance, beauty, and harmony around us, acting as protectors of the natural world.

Today the kauri groves suffer from kauri “dieback,” an infestation of microscopic fungi that eventually kill the tree. Many Māori believe that the health of the forest is an early indication of the health of the oceans and society’s general well-being.

It is true, the world faces many environmental and social challenges in the decades to come. Back home, climate change and resulting heat waves and intense fires have put unprecedented stress on the coast redwood groves in California as well as on the pine forests and delicate high-desert ecosystems of Northern Arizona.

When I think about potential solutions to these challenges, I am heartened to know that our forests offer some of the most effective solutions to combating the climate crisis. Old-growth coast redwood forests store more carbon per acre than any other forest type ever measured. Therefore, the protection and expansion of our natural forests is critical to our global efforts to reduce emissions and draw down what we’ve already emitted.

In recent studies, scientists are finding evidence that spending time in local forests has measurable positive impacts on one’s physical and mental well-being, lowering stress levels and anxiety, while increasing mental clarity and creativity, benefitting overall health. This research confirms what my Diné elders and Native communities have taught for thousands of years: that we are the land and the trees, and being among them, showing our respect, provides great healing, beauty, and balance.

The immigrant redwoods of New Zealand also offer insights into how to live without overstepping one’s ecological limits. The redwoods here thrive, soaking in the nutrient-rich soil, but do not flourish at the expense of the smaller native flora and fauna. The redwoods have found a way to blend seamlessly into the unique give-and-take cycles of their new home, earning the title of “naturalized” and not “invasive.”

As we near the end of the Tokorangi Redwood Memorial Grove track, I turn, close my eyes and breathe in the woody evergreen aroma of the redwoods mixed with the damp earthy scent of the nearby giant ferns and beech trees. I leave feeling invigorated, reminded that there is healing in remembering where we are and how we can all live as naturalized stewards to the land and forest.

6 Responses to “How to Exist on Indigenous Land, According to Redwoods”

David Collins

Enjoyed the story!!! Glad to hear Red Woods thriving in other countries.

William Owens

Please explain the distinction between, “invasive,” and, “naturalized.” What are the indications that a non-native plant is naturalized but not invasive?

Garrison Frost

“Naturalized” is not a technical term in the world of forestry. The redwoods would probably still be considered invasive in that they do not naturally occur in New Zealand. But the author uses the term “naturalized” to suggest that the redwoods aren’t causing the degradation one often sees with invasive flora. Moreover, despite its introduced status, the redwoods have also developed quite a following.

KEN & GAY Hazen

Several years ago we visited New Zealand, becoming more impressed with the Maori and

immigrant population. The North Island redwoods make you shake your head (to reset

your GPS)…… where am I? Are the Rainbow trout still present (or were they deemed an

invasive species?) Found further attachment near Christchurch when we encountered

a rainbow of rhododendrons. Must have been impressive to have existed when New Zealand

cleaved from California!!

Ron Hagg

I’ve lived around and under redwoods for years. My two children were born at home under redwood trees. I’m now just north of Taos, New Mexico. Very much enjoyed your story. Anyway – take care and thanks.

nathan hutchinson

Beautiful story. thank you for sharing