The InterTribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council is restoring Indigenous guardianship to traditional Sinkyone lands and waters

Save the Redwoods League and the InterTribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council in December 2021 finalized key transactions in their partnership to permanently protect coast redwood forestland within Sinkyone traditional territory on what is popularly known as the Lost Coast in Mendocino County, California. The League purchased the 523-acre property, formerly known as Andersonia West, in July 2020. To ensure lasting protection and ongoing stewardship, the League donated and transferred the forest to the Sinkyone Council, and the Council granted the League a conservation easement.

Through this partnership, the Sinkyone Council returns Indigenous presence to a land from which Sinkyone people were forcibly removed generations ago. This forest will again be known as Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ (pronounced tsih-ih-LEY-duhn), meaning “Fish Run Place” in the Sinkyone language.

Here, the Sinkyone Council reflects on the return of the land to their guardianship.

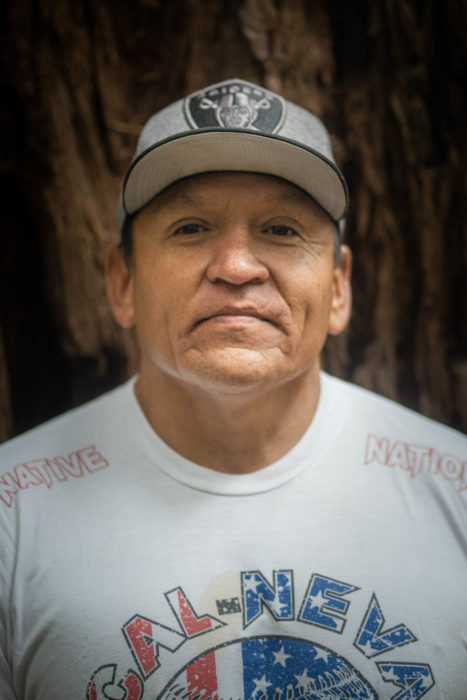

“The protection of Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ means everything because this is how we’ve survived. This is who we were and are. Enough has been taken away. If we can do anything to help preserve the land, the wildlife, nature—we want to be a part of that. Because that’s us.”

–Jesse Gonzalez, Eastern Pomo/Sinkyone/Cahto, tribal citizen of Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians, and alternate board member of the Sinkyone Council

The InterTribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council is honored to be the holder of Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ, to restore Indigenous guardianship and relationship to this special place, and to work in partnership with Save the Redwoods League in the permanent protection and care of this coastal forest.

“The Sinkyone Council has designated Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ as a Tribal Protected Area. This designation recognizes that this place is within the Sinkyone traditional territory, that for thousands of years it has been and still remains an area of importance for the Sinkyone people, and that it holds great cultural significance for the Sinkyone Council and its member tribes. Tribal Protected Area designation also means we and the League have a mutual commitment to respect, safeguard, and tend Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ in ways that ensure its long-term protection, care, and healing.”

–Priscilla Hunter, Northern Pomo/Coast Yuki, tribal citizen of Coyote Valley Band of Pomo Indians, and chairwoman of the Sinkyone Council

Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ not only is the homeland of Sinkyone people, but also holds more than 200 acres of old-growth coast redwoods that stand among Douglas-firs, tanoaks, and many other plants sacred to the tribes of the region. It also is a place where relatives such as the northern spotted owl, marbled murrelet, and coho salmon belong. Part of the work we do as Indigenous Peoples is to honor these relatives, these beings who, like our peoples, have been here for thousands of years.

“Being able to see land that has always been locked up, chained up, or blocked off from us is incredible—to see where we roamed at one time.”

–Chris Ray, Sinkyone/Cahto/Wailaki/Eastern Pomo, tribal citizen and elder of Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians, and alternate board member of the Sinkyone Council

Despite the atrocities committed against us, our ancestors’ perseverance kept traditional knowledge and ways alive, enabling our cultures to revitalize and become stronger with every generation.

“Many lost their language, and language is really core to what we were doing in a cultural society. When grandfather passes on culture to grandson, there’s a lot of missing links to that passage, because grandfather was a product of a system that didn’t allow him to be who he was as a Native person inside. So as a protection measure, sometimes he had to say to grandson, ‘I’m not sure if we want to do this, but here are some songs, here’s some ceremony, this is what it looks like.’”

–Jaime Boggs, Eastern Pomo/Wailaki/Concow, traditional singer and dancer, tribal citizen and council member of Robinson Rancheria of Pomo Indians, and board member of the Sinkyone Council

Today, in restoring the original place name Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ, we exchange a reciprocal gift of love and respect for Indigenous land and language with ancestors and future generations. Our languages are related to the sounds of this earth. They are aligned with the languages of animals, plants, waters, tides, and all parts of nature that speak. Those ways of speaking have contributed to our own tribal languages, which enable us to communicate with nature.

“Intergenerational trauma means that human people experience grief and harm inherited from past generations that can affect them profoundly. And so the land is no different. It’s comprised of communities of living organisms that also have been harmed and traumatized. If we learn to pay attention, we can better understand how the land experiences trauma and thereby gain compassion, understanding, and respect that can be instilled into our ways of life. Thus, we can help in healing places like Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ.”

–Hawk Rosales, Ndéh (Apache), Indigenous land defender, and former executive director of the Sinkyone Council

Recognizing Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ as a Tribal Protected Area reaffirms the inherited responsibility tribes have to maintain and revitalize our relationships with the land, air, water, spirits, and all forms of life within our cultural landscapes. Tribal culture and land protection are inextricably linked; Indigenous cultural lifeways depend upon the health of the lands and waters.

“I imagine my ancestors traveling our traditional lands—I could see them trading baskets. Us coast people would go fishing and get seaweed, shells, abalone, and trade it inland with Eastern Pomo people, where they might have bulrush, which is used for our basketry, or willow.”

–Buffie Schmidt, Northern Pomo basket weaver, tribal citizen and vice chairperson of Sherwood Valley Rancheria of Pomo Indians, and board treasurer of the Sinkyone Council

The Sinkyone Council’s goal for Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ and other places is to expand the matrix of neighboring protected lands that are ecologically and culturally linked, so that the tribes can achieve larger landscape-level and regional-level protections informed by their cultural values and understandings of these places. In this way, Indigenous Peoples will support and participate in the healing of these lands and their communities.

“Having a place that still has redwoods, still has a connection to the land, to me lets me know that we have sacred places that are protected for my children and grandchildren and the future of our tribal people and our Native people in California. A place to go to, a place to remember.”

–Crista Ray, Sinkyone/Cahto/Wailaki/Eastern Pomo, tribal citizen of Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians, board member of the Sinkyone Council, and daughter of Chris Ray

This feature appears in the beautiful printed edition of Redwoods magazine, a showcase of redwoods conservation stories by leading scientists and writers, as well as breathtaking photos, and ways you can help the forest. Only a selection of these stories are available online.

Join our thousands of members today for only $25, and you’ll get future editions of our Redwoods magazine.

One Response to “Protecting Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ”

Julie Carville

Thanks to each of you for introducing yourselves as members of the Sinkyone Council. It was meaningful to hear directly from each of you, so personal and moving, as you expressed your own sacred love of Nature. I’m very grateful for the strength of each of you and your people over generations, and for the work each of you have been doing, so that your wisdom and values are awakening the public and organizations to listen to you and respect your wisdom. Your cooperation with the Save the Redwoods, as you take on the protection of this land in the Redwoods, is the kind of cooperation that will bring healing to all of us and to Nature. Thank you so very much, Julie Carville