Restoring Yurok names on the North Coast a step toward a "more just world"

In a deep voice, Yurok Tribal chairman Joseph James began a traditional song. ‘O Rew, the Yurok name for the surrounding land, was about to make history. That day, Save the Redwoods League, Redwood National and State Parks, and the Yurok Tribe would sign a landmark agreement to return ‘O Rew to the Tribe, setting the stage for a new Indigenous-owned gateway to the national park.

Many important changes had been made to this land since 2013, when the League purchased the property, then known as the Orick Mill Site. But perhaps the most poetic was the choice to revert to the original Yurok place name: ‘O Rew.

For the Yurok Tribe, the place called ‘O Rew recalls a time of abundance. Before colonists arrived in Northern California, Yurok villages stretched along the Klamath River and the Pacific coastline. Interconnecting trails meandered through the old-growth redwoods, many passing through ‘O Rew. At the heart of the site was Prairie Creek, home to salmon, elk, migrating birds, and other riparian wildlife.

Colonial place names carry dark history

According to Yurok historical documents, when Euro-Americans arrived and stole land from the Tribe, the colonists renamed almost every landmark. Tribal members were forced to learn English, and Yurok children were shipped to government-sponsored boarding schools with the goal of eliminating cultural and religious teachings. The children were abused for speaking Yurok and soon the language started to disappear.

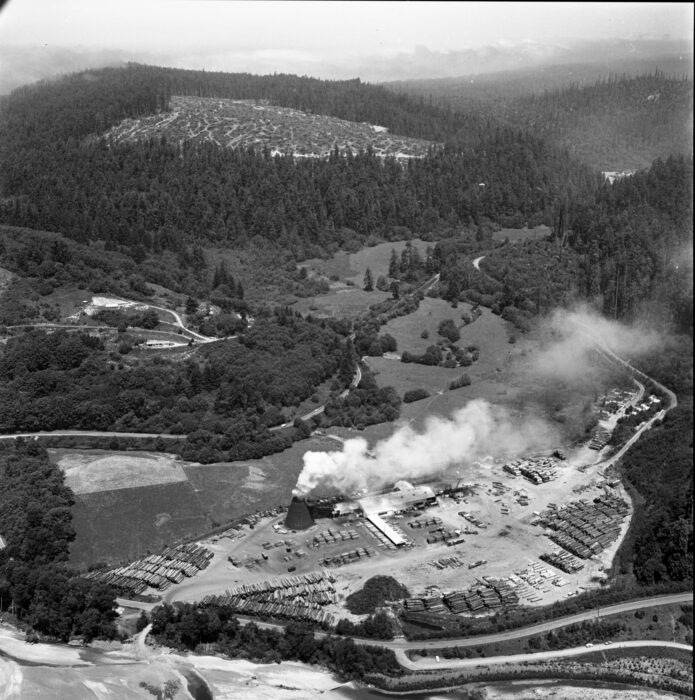

At the same time that Yurok culture was being systematically suppressed, the ancient redwood forests was being clear-cut, forever altering the Tribe’s ancestral homeland. Eventually, a sawmill for processing the old-growth trees was built on the ‘O Rew site outside of Orick, California, causing tremendous environmental degradation to Prairie Creek and the surrounding floodplain. Yurok Tribal council member Phillip Williams, who worked at the mill in the 1990s, described it as a dirty place, “full of waste, oil, and chemicals to preserve the wood and keep the machines going.”

Even after the sawmill closed in 2009, the moniker “Orick Mill Site” was a painful reminder of the desecration of the beloved old-growth forests. Restoring the original name of ‘O Rew presented an opportunity to create a different future—one led by the Indigenous community, with hope for the future and respect for the past.

Indigenous names bring healing at state park sites

‘O Rew isn’t the first site along the North Coast to have its Yurok name restored. At Patrick’s Point State Park in Trinidad, California, Yurok community members had long argued that the park’s namesake, Patrick Beegan, had murdered Native people and stolen Yurok land. In 2021, the State Parks Commission voted to restore the original Yurok name of “Sue-meg” to these 640 redwood- and oak-shaded acres. Sue-meg State Park would become the first California State Park renamed under the park system’s Reexamining Our Past Initiative.

After the renaming, Chairman James told the Times-Standard, “We asked the commission to alter the name of the park because we have an obligation to ensure the next generation inherits a more just world.”

Another success story unfolded on the eastern edge of Stone Lagoon, located within the Humboldt Lagoons State Park. According to Nicole Peters, interpretation coordinator for the Yurok Tribe, the Yurok rarely came to the site’s visitor center when it was called Stone Lagoon because the center had not been created for Indigenous people. The Yurok Tribe worked with California State Parks to identify and remove these cultural barriers. Not only was Chah-pekw ‘O’ Ket’-toh unofficially reclaimed as the site name, but in 2022, Chah-pekw ‘O’ Ket’-toh “Stone Lagoon” Visitor Center became the first tribally operated visitor center in the state park system.

“Reclaiming a name is a chance to educate,” says Peters. “We get to show [visitors] who we are, the bad things that happened, and the good things we’ve done. We get to be a part of the change.”

Owning their story, reviving the Yurok language

Rosie Clayburn, Tribal heritage preservation officer and cultural resources director for the Yurok Tribe, sees a similar opportunity to shape the narrative at ‘O Rew Redwoods Gateway. “We have seen what happens when we are not interpreting our culture, when we are not the ones telling our story,” says Clayburn. “This site allows us to tell you what we want to tell you about our history and our future.”

Closely tied to these projects is an ongoing effort to revive the Yurok language, which had almost gone extinct in the early 1900s. With funding from the Administration of Native Americans (ANA), the Tribe created a long-term language revitalization plan and teacher training program. Yurok is now taught in five local high schools, and language acquisition has been integrated into the elementary and middle school curriculum. Yurok classes are also being offered in the community, with the goal of integrating the language within households, workplaces, and community events. Says Clayburn, “The hope is to keep pushing Yurok into all aspects of our homeland.”