Research shows birds live close to their release sites

Research supported by Save the Redwoods League could help inform work in re-establishing a flock of endangered California condors near Redwood National Park. The Yurok Tribe and Redwood National Park are working together to re-establish the prey-go-neesh, the Yurok name for the California condor, the endangered avian scavenger that nearly went extinct half a century ago. In 2021, the organizations released eight young birds, which are a cultural touchstone for the tribe and a keystone species of redwood ecosystems.

While an undergraduate student at Cal Poly Humboldt University, José Juan Rodriguez Gutierrez was considering research topics when he came across a story about prey-go-neesh returning to the skies above redwoods country.

“I was hooked from the get-go,” says Rodriguez. “This was a great opportunity to be part of something that meant so much to the local community, the Yurok Tribe and everyone else who has followed condor conservation.”

Rodriguez received a Starter Grant from Save the Redwoods League to fund his project, called Condors and Redwoods Ecological Research. The grants are for undergraduate and graduate students of color who are interested in research in coast redwood and giant sequoia forests. The funding provides introductory opportunities for members of underrepresented communities to explore ideas in redwoods research.

Under Wildlife Department Assistant Professor Ho Yi Wan, who specializes in spatial and landscape ecology, Rodriguez designed a project to map home ranges of 12 condors released in Central and Southern California in the period from 2016 to 2020. Using two different methods, he compared how home range sizes varied among individuals, between flocks, and from year to year. He discovered that the condors spent a lot of time near their release sites, but that Southern California condors ranged far more widely than Central California birds. The home ranges of all the condors expanded in 2017 and 2018, then decreased.

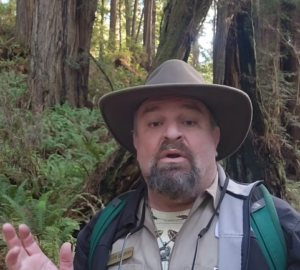

Condors still face many threats in the wild; seven out of the 12 condors Rodriguez studied have since died, either from lead poisoning or in wildfires. Analyzing condors’ home ranges can help conservationists better understand the habitat characteristics they seem to prefer, says Gutierrez. “It would also allow us to come in and see what those hot spots have to offer, or what protections we can put around these focused areas.” Rodriguez especially hopes his project can ultimately help the Yurok Tribe manage the newest flock of condors. He made the video above about condor conservation.

Rodriguez has since graduated with a degree in Wildlife Biology & Communications and is currently gaining field experience as an aquatic restoration biologist for Redwoods Rising, a project of Save the Redwoods League, the National Park Service, and California State Parks to restore historically logged areas in Redwood National and State Parks.

One Response to “Saving prey-go-neesh, the endangered California condor”

Tony Antinoro

Thank you for your enthusiasm. Interesting and worthy of our support.