Forest restoration projects are bringing jobs and opportunity to California's North Coast

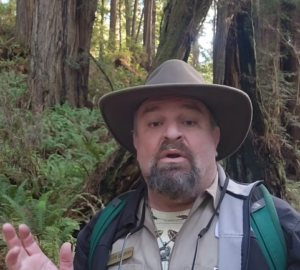

On a sunny spring morning, Briyan Marquardt stands on a gravel road overlooking the Mill Creek watershed in Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park. Wearing a silver hard hat and a chest harness that holds his radio, cell phone, compass, work gloves, and pink flagging tape, he’s supervising a crew of timber fallers 1,600 feet below. Their mission: to thin the stands of stunted redwoods that grew back after this forest was logged more than half a century ago.

Marquardt used to work for a logging company, falling trees for timber. Now he works to heal the redwood forest as a contractor for Redwoods Rising—a collaborative restoration project between Save the Redwoods League, California State Parks, and the National Park Service. Not only is the job more meaningful, but the hourly wage is much higher.

The extra pay has allowed the Army veteran to save money—for a possible home purchase, retirement, his family. “I just found out I’m about to be a grandpa,” says Marquardt. “Saving more money means I can help my daughter and her fiancé get set up for their lives, which for me is pretty huge.”

Marquardt is one of hundreds of North Coast workers benefitting from a restoration economy fueled by efforts to heal the redwood forests. The most ambitious of these projects is Redwoods Rising, a decades-long program to restore more than 70,000 previously logged acres within Redwood National and State Parks (RNSP). Over a century of industrial logging left isolated ancient groves surrounded by dense regrowth with little biodiversity. Thinning these cluttered stands gives young redwoods the space and sunlight they need to thrive. Crews are also removing 300 miles of logging roads and restoring buried and eroded streams that are critical to threatened salmon and steelhead.

Acre by acre, Redwoods Rising is laying the foundation for the old-growth redwood forests of the future. But for Marquardt, the benefits are already clear. “I definitely enjoy the heck out of this job. Instead of going in and doing a clear-cut, you can turn around and say, this looks gorgeous. We’ve opened it up so the redwoods can actually start growing now. You give it a couple years and it’ll look a heck of a lot different and healthier.”

At the southern entrance to the parks, crews are restoring another degraded redwood landscape, transforming the former site of the Orick Mill into the ‘O Rew Redwoods Gateway. Workers have already peeled away 20 acres of asphalt, restored 18 acres of floodplain along Prairie Creek, and installed native shrubs and grasses—all part of the vision shared by Save the Redwoods League, the Yurok Tribe, the National Park Service, California State Parks, and other partners. Hiking trails and exhibits are currently being added, and plans include a traditional Yurok village for cultural and interpretive activities.

In 2026, the League will transfer the property to its original stewards, the Yurok Tribe, for permanent protection and recreational access. ‘O Rew will serve as a national model for government and nonprofit partners to support co-stewardship on tribal lands. Locally, it will be a step toward revitalizing gateway communities and connecting visitors not only to the parks but also to the cultures rooted in this land.

Measuring the restoration economy’s impact

This remote part of Northern California is known for its fog-shrouded landscapes, wild rivers that empty into the Pacific Ocean, and vast forests of towering redwoods. But alongside its natural beauty, the region faces issues common to rural communities across the country, including limited job opportunities, lack of health care services, food insecurity, and challenges with transportation.

Against this backdrop, a new socioeconomic report funded by the Redwood Parks Conservancy details how large-scale forest restoration is helping to bring economic resilience and steady, well-paying jobs to the North Coast. “Assessing the Restoration Economy within Redwood National and State Parks” shows that Redwoods Rising and ‘O Rew supported an estimated 475 jobs and contributed an estimated $95 million in economic output between 2022 and 2024. This includes direct impacts, such as the wages earned by staff and contractors working directly for Redwoods Rising; indirect impacts, which include expenses such as fuel purchases for restoration work; and induced impacts, which include workers spending their wages on groceries and housing.

“The report’s findings are profound,” says Redwoods Rising Project Manager Mitchell Hayes. “Not only are we creating jobs, we’re creating opportunities that pay well enough for some people to buy homes and build stable lives in a region where that’s not easy.”

This economic uplift is fueled by the significant public and private investment that ‘O Rew and Redwoods Rising are bringing into the region. Of the $97 million raised as of February 2024, more than $44.5 million came from hard-won state and federal grants, while generous private donations and fundraising generated another $10 million.

Redwoods Rising is also partially funded by sales of biomass—the vegetation and small-diameter trees removed during restoration thinning—for use as lumber, chips, or biofuel. From 2020 to 2023, biomass sales yielded $18.5 million in revenue that was reinvested in restoration, creating a self-sustaining funding loop. Additionally, biomass sales generated $350,000 in timber yield tax revenue for Humboldt and Del Norte counties—money local governments can invest in public health, housing assistance, and other programs that improve community well-being.

This is especially significant for tribal communities, which face greater economic inequality due to the history of settler colonialism, violence, and extractive practices that harmed their land. Restoration is taking place in the ancestral homelands of the Yurok, Tolowa, and Chilula peoples, and the work is often led by Indigenous restoration experts. This tribal leadership is central to both healing the land and promoting more equitable economic growth.

“RNSP restoration projects not only create stable, well-paid jobs for the Yurok Tribe, but also create opportunities to strengthen cultural and spiritual connections to their treasured landscape,” says David “DJ” Bandrowski, senior civil engineer for the Yurok Tribe. (The Yurok Tribe Construction Corporation has done aquatic restoration at both ‘O Rew and Redwoods Rising sites.) “The Yurok have always been stewards of the land—the approaches they are implementing today are not new. The landscape has been managed since time immemorial to maintain the delicate balance of the ecosystem. We are merely restoring that balance.”

Moving beyond boom and bust

Just as Detroit’s economy was built around the automobile, the North Coast economy once relied heavily on timber. Logging of the ancient redwoods began in the mid-1800s following the discovery of gold in the area. After World War II, a construction boom drove demand for redwood lumber. According to the socioeconomic report, by 1950 more than 250 sawmills were operating in Humboldt County, and lumber output was the second highest in the country.

But overharvesting and a dwindling supply of old-growth redwoods soon put the brakes on the lumber boom. The North Coast timber industry began to shrink, while at the same time, advances in technology made certain logging jobs obsolete. Amid these challenging economic shifts, some residents saw the establishment of Redwood National Park in 1968—and the park’s expansion a decade later—as the end of an era. As the nation entered a recession and inflation soared, the new park became a focal point for resentment in struggling logging communities. For many, the idea of conservation being compatible with good jobs was now inconceivable.

The 1996 legalization of medical marijuana offered a temporary economic lifeline, with cannabis cultivation exploding in the “Emerald Triangle” of Humboldt, Trinity, and Mendocino counties. But the legalization of recreational marijuana in 2016 led to a sharp drop in prices and another bust. Today, income levels in both Humboldt and Del Norte counties remain below state and national averages. According to the socioeconomic report, half the population of Del Norte County and 29 percent of Humboldt County residents fall within a federally designated Disadvantaged Community, identified as those that are marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution.

Long-term restoration projects offer an alternative to such precipitous boom-and-bust cycles. Broadening the area’s economic focus to include ecological restoration, wildlife conservation, and forest management means communities are less vulnerable to financial downturns. Conservation jobs are more varied and they pay more than the county average. Plus local workers are prioritized: More than 90 percent of Redwoods Rising direct work hours are filled by North Coast staff and contractors, which helps keep money in gateway communities. And because two-thirds of RNSP consists of previously logged land, efforts to repair these forests are expected to continue well into the future.

Restoration work is not only more secure, it’s also less seasonal, which makes a big difference to folks like Ken Strombeck. The Crescent City resident used to work as a hook tender for commercial loggers, but the companies often shut down for the winter. “So you’re drawing unemployment, and that’s $1,800 a month,” he says. “It gets rough.” Now Strombeck is able to work year-round as a process operator for Redwoods Rising. “I don’t have to draw unemployment,” says Strombeck. “I don’t live paycheck to paycheck.”

These benefits extend beyond workers on the ground to the many contracted companies supporting restoration. For the past two years, Hemmingsen Contracting Company, a family-owned business founded in 1963 in Crescent City, has been supplying rocks to stabilize roads for Redwoods Rising. “It’s been a big influx on our business. It’s really helped,” says owner Steve Hemmingsen, adding that he’s been able to buy a couple more trucks and hire more drivers. This in turn supports local businesses that sell fuel and provide maintenance and repairs.

Another Crescent City company getting a boost from restoration contracts is Babich Trucking, which supplies trucks to haul logs and move equipment. “Overall, it has helped us grow the business,” says manager Trevor Babich, who estimates Redwoods Rising has increased his company’s workload by about 15 percent. The added business has allowed the firm to buy newer trucks, which means less maintenance and more efficiency.

And because the work is steadier, Babich is better able to retain drivers. “Around here, there’s very little to choose from, unless we leave town,” he says. “[Restoration work] has actually helped keep the trucks in town, keep the guys at home every night.” Workers being closer to home and family may be one reason why, according to the report, some organizations indicated that increased local employment has “decreased rates of divorce and drug use among their workforces.”

“It’s a glimmer of hope that highlights how important it is to keep up our momentum,” says Hayes. “This work demonstrates that we can create secure employment while also supporting ecological restoration”—a combination once deemed impossible by many in these parts.

A small town looks toward the future

Drive half an hour up Highway 101 from Arcata and you reach Orick, a small town at the doorstep to Redwood National and State Parks. At the peak of the commercial timber industry, Orick’s population exceeded 2,000, and there were nine sawmills in or around the valley. Today, the town has fewer than 400 residents and only a handful of businesses.

This absence of bustling shops, restaurants, and hotels means that most tourists tend to drive straight through. But that may soon change with the opening of the visitor gateway at ‘O Rew, which could be an engine for economic growth. Already, restoration work in the area is helping to inject new life—and hope—into this tiny hamlet.

On a weekday in Orick, a worker in a green safety vest stands outside a tiny red trailer along the highway, eating a slice of pepperoni pizza. Inside the trailer is the wood-fired oven where Mojo Pizza owners Molly Murphy (“Mo”) and Jordan Greco (“Jo”) bake their pies—a mix of Neapolitan and New York–style pizza that emphasizes locally sourced ingredients.

When Murphy and Greco opened their business in 2024, they assumed tourists would make up the bulk of their customers, and that they’d be busiest on weekends. But then restoration workers began showing up during the week—sometimes every day. “It was a big part of our income,” says Greco. Business soon exceeded expectations. They were “stoked.”

In their first month of business, Greco and Murphy made their own pizza dough by hand. But thanks to the added business from restoration workers, they were able to buy a large Hobart dough mixer. “It saved our bodies so much,” says Murphy.

Such is the ripple effect of restoration workers with money in their pockets spreading those dollars throughout the community. In 2024 alone, direct work for Redwoods Rising and ‘O Rew brought an estimated $12.3 million in available earnings to Del Norte and Humboldt counties. That’s not insignificant in a region with lower median household income levels and higher rates of unemployment than national averages.

While not all business owners see immediate gains, some, like Carrie Greenlaw, are hopeful about the future benefits of restoration. Greenlaw is the owner of Roosevelt Base Camp, a restored 1950s motel in Orick that opened in 2022 with just six rooms. Greenlaw says she’s optimistic that restoration in the parks will eventually increase tourism and help her business. “With the restoration project and everything going on, people know these things are happening, and they want to see it for themselves.”

Tourism already makes a significant contribution to the North Coast economy. According to a National Park Service report, the more than 400,000 people who visited Redwood National Park in 2023 spent $29.6 million in gateway communities and supported over 380 jobs. Another 850,000 people visited nearby state parks, including Jedediah Smith, Prairie Creek, and Gold Bluffs Beach. Although increasing tourism is not the focus of Redwoods Rising, it’s a likely future outcome. Healthy forests and rehabilitated streams support an exceptional park experience—one that will endure for generations, through climate change or budget shortfalls. Park visitors, in turn, will spend money in gateway towns, creating a positive feedback loop between the recreation economy and the restoration economy.

Greenlaw notes that demand for lodging already exceeds availability, and she’s aiming to open another 10 rooms in the near future. More rooms equal more business and the ability to hire more staff—another example of restoration’s multiplier effect. Last summer, Greenlaw and her fiancé also purchased the adjacent movie theater. They’re in the process of gutting it, and her daughter is hoping to open a bakery and coffee shop in the storefront. “We’re excited to do something to bring Orick back,” says Greenlaw. “And help people get away from the rat race and see the redwoods.”

The legacy of logging comes full circle

The timber industry remains active on the North Coast, and some communities still celebrate its heyday. In the window of Hagood’s Hardware in Orick, faded photos show a truck hauling a huge redwood log and men posing with their axes wedged into an old-growth giant—reminders of how so many livelihoods were once proudly tied to timber.

But speaking with workers and residents, there’s a genuine enthusiasm for Redwoods Rising and ‘O Rew that goes beyond financial gain. One gets the sense that these projects are galvanizing people around the value of conservation and the importance of restoring redwood forests. Many express gratitude for the work—and the mission. They’re excited to be involved in something that will have a meaningful impact, as well as more immediate benefits to the landscape.

Marquardt mentions how a lightning fire started in a forest that restoration crews had previously thinned—and how the fire didn’t get out of control. “All it did is burn the brush,” he says. “It didn’t get into the canopy, and it’s still a healthy forest.”

Strombeck notes how a year after crews had thinned another area, which allowed more sunlight in, the rhododendron bushes bloomed. “There were flowers everywhere,” he says. “It was just beautiful.”

As for Babich, he talks about a shift in sentiment among community members as they witness local workers returning to the forest for restoration. “A lot of them are happy,” says Babich. “They’re like, ‘Now you guys get to go back in there and open it up but create that healthier environment.’ ”

On the North Coast, there’s a sense that restoration is bringing the legacy of logging full circle. The skilled laborers, tradespeople, and heavy equipment operators who make Redwoods Rising and ‘O Rew happen are using timber falling and logging skills passed down through generations. They are healing the redwood forests—while also healing relationships, people, and local communities. Each day on the job, they’re letting in a little more light.

This feature appears in the beautiful printed edition of Redwoods magazine, a showcase of redwoods conservation stories, breathtaking photos, and ways to help the forest. Only a selection of these stories are available online.

Join our thousands of members today for only $25, and you’ll get future editions of Redwoods magazine.

2 Responses to “Healing the forests, building the restoration economy”

Kit Frost

Great article about Orick and the gateway to the Redwoods National and State Parks. I recently spent a month based in Orick as an Artist in Residence and enjoyed the coffee wagon, MoJo’s pizza!, shopped locally at the Orick Market, and noticed the old movie theater being renovated. Hosted by the Redwoods Parks Conservancy, I was able to see the ‘O Rew planting and restoration work on my way up to the Lady Bird Grove, and visited a site of the Redwoods Rising Project too. I think it will be awesome when the continued improvements take place in Orick and can imagine in a few years the transitions from a mill town to a sweet gateway to our beautiful Redwoods on the North Coast. Thanks for all the Save the Redwoods league, the Yurok Tribe and many others are doing. I can’t wait to visit the newly built ‘O Rew Redwoods Gateway in a few years.

Rosemary Graham-Gardner

This planet would die if it weren’t for the trees and all of its inhabitants…