Federal agencies and the Yurok Tribe partner to reintroduce California condors to Redwood National and State Parks.

The great creature is unmistakable when viewed from below as it glides on broad black-and-white wings. With a nine-foot wingspan longer than some cars, the California condor is the largest bird in North America.

Condors once commanded the skies from British Columbia to Baja California until the 19th and 20th centuries, when the giant vultures fell victims to shooting, egg collecting, habitat degradation, and the intentional lacing of carcasses with poison to reduce predator numbers. Poisoning from ingestion of lead ammunition in carcasses was also a major contributor to the decline. The federally endangered bird had dwindled to just 22 individuals in 1982. Since 1992, when the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) began reintroducing captive-bred condors to the wild, the agency and its partners have grown the population to more than 518 birds, with 337 of them flying free.

Before too long, visitors to Redwood National and State Parks may spy the condors, which have been missing from the area for more than 100 years.

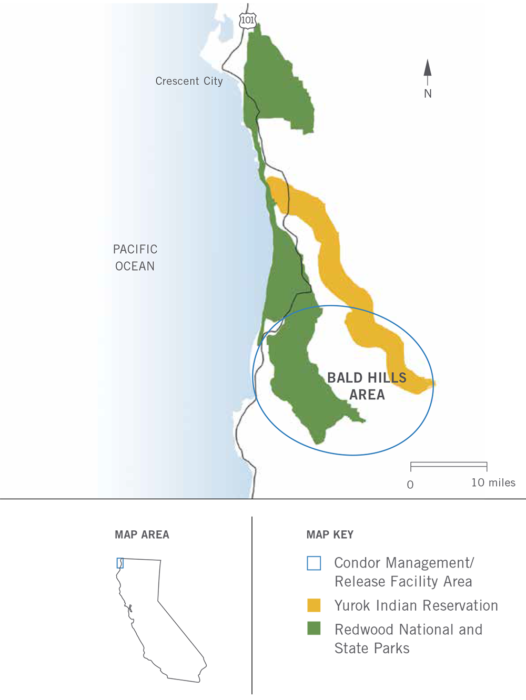

Overlapping portions of the park is the ancestral territory of the Yurok Tribe, which is leading the effort to reintroduce the California condor to the Pacific Northwest. The National Park Service and USFWS are partners in the project.

The condor figures prominently in the Yurok Tribe’s World Renewal ceremonies, where Yuroks pray and fast to balance the world.

“It’s our understanding of the world that if any component is missing, the system is unbalanced; it’s unable to right itself,” said Tiana Williams-Claussen, Director of the Yurok Tribe Wildlife Department. “That’s actually why we’re here as Yurok people, to help manage the landscape in a balanced way.”

In 2003, a task force of Yurok elders determined that the California condor was the single most important terrestrial species to return to ancestral territory, in large part because of the tribe’s cultural connection to the bird.

“He’s a good indicator for ecosystem health, which is why a lot of our initial work was geared toward developing habitat assessments and contaminant analyses,” Williams-Claussen said. “[We wanted] to make sure that if we were to bring Condor home, we had a safe place to bring him home to.”

BENEFICIAL HABITAT

Dave Roemer, Deputy Superintendent of Redwood National Park, said the region has “all the right ingredients” for condors: wind, slopes and ridges to create lift, nesting trees, and abundant food. Condors are scavengers, feeding exclusively on large animal carcasses, from whales and sea lions to deer and elk.

The reintroduction project aligns with the park’s mission, he added. “Bringing [condors] back is going to mean something, not just for the narrower goal of endangered species recovery, but for the broader goal of tribal sovereignty.”

Amedee Brickey, Assistant Regional Director for USFWS Pacific Southwest Region’s Migratory Birds & State Programs, said the project fulfills her agency’s goal of returning species to their historical ranges. A National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review, required under the Endangered Species Act, is in the final stages. USFWS is helping guide the policy review, working with industry stakeholders, securing funding for the review, and obtaining captive-bred birds.

Condors are heavy at 15-21 pounds, which is one reason the Bald Hills region, with its strong upward currents of warm air, has been identified as a favorable release site. If all goes well with the NEPA review, Yurok Tribe biologists will erect an enclosure this winter and welcome the first juveniles, which will have been raised in one of several participating breeding programs. They will spend a few months in the enclosure acclimating to the environment before being released.

Biologists will track the birds using satellite transmitters. They also will continue baiting the release site with carcasses so they can lure the birds back for health checks. Once a population is established, juveniles from breeding programs will continue to supplement wild-hatched birds.

THE THREAT OF LEAD

The condor’s biggest challenge is poisoning from ingesting lead ammunition, Brickey said. When a lead bullet hits a deer or other mammal, it scatters into hundreds of pieces, some large, some microscopic. After hunters gut a carcass in the wild, they often leave the remains, which condors and other wild animals eat.

Although California has banned lead ammunition for hunting, not all individuals will follow set rules without understanding why they were created, said Chris West, Yurok Tribe Condor Restoration Program Manager. “It’s critical to empower hunters and shooters with trustworthy and accurate information about how lead ammunition can harm wildlife,” he said. “They also need information on the effectiveness of new technologies, like non-lead ammunition. Hunters and shooters must be embraced as partners and the stewards of wildlife as the majority of them are.”

Toxicosis, the resulting disease from lead ingestion, remains the leading cause of mortality among condors in the reintroduced populations, Brickey explained. However, lead levels within turkey vultures in the Redwood National and State Parks region are lower than in areas where condors are already regaining a foothold.

All of the partners are optimistic about the project’s success—and they are eager to see the birds soar above the giant trees once again.

“Anybody who sees Condor in the sky uses words like ‘magnificent,’” Williams-Claussen said. “He’s the sort of guy who really reaches the heart when you see him.”

CALIFORNIA CONDOR REINTRODUCTION

What

With a nine-foot wingspan, the California condor is the largest bird in North America. The Yurok Tribe and federal agencies are working to bring federally endangered California condors back to Redwood National and State Parks and Yurok ancestral territory. The birds have been missing from the area for more than 100 years.

Where

The Bald Hills area at the southern end of Redwood National and State Parks and the Yurok Indian Reservation, about 40 miles south of Crescent City, California.

When

Birds may be released in 2021.

Learn More

This feature appears in the beautiful printed edition of Redwoods magazine, a showcase of redwoods conservation stories by leading scientists and writers, as well as breathtaking photos, answers to readers’ questions, and how you can help the forest.

Join our thousands of members today for only $25, and you’ll get future editions of our Redwoods magazine.