Applying the lessons of the Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative

Writer John Steinbeck called redwoods “ambassadors from another time,” while W.E.B. Du Bois described them as “eternal wooden stone with tremendous grip on earth.”

We search for words to describe the majesty of the coast redwood and giant sequoia forests, to find words to capture these towering red trees and our emotions around them.

It’s easy for us to forget that these trees are also dazzling examples of natural functions. For instance, every redwood is a complex pumping system that collects water from the soil and transports it hundreds of feet high. It is also a structure perfectly designed to support several different ecosystems, including hundreds of different plants and animals high above the ground.

And perhaps most interestingly, for the purposes of this article, every one of these trees is an incredibly efficient machine that uses sunlight and water to take carbon dioxide from the air and convert it into sugar to build immense amounts of wood at an incredibly high rate—storing that carbon safely out of the atmosphere for centuries.

This carbon storage has become an increasingly important factor in the conservation and restoration of these forests, nearly as much as the treasured aesthetics that have historically been the main drivers of their protection.

THE CLIMATE CHALLENGE

The most recent report from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is perhaps its most alarming, warning that unless action is taken to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, the Earth will pass a dangerous temperature threshold in the next 10 years, deepening ecological damage and economic calamity.

Acknowledging the dire warning in the report, IPCC Chair Hoesung Lee tried to strike a positive note: “This Synthesis Report underscores the urgency of taking more ambitious action and shows that, if we act now, we can still secure a livable sustainable future for all.”

Here in California, when we seek an avenue of hope, we often turn to nature and the redwoods. And not just for their beauty.

Concerned at the prospect of climate change joining logging and development as threats to coast redwood and giant sequoia forests—but also intrigued at the potential that these forests could somehow help solve the crisis—Save the Redwoods League in 2009 launched the Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative. The initiative itself would evolve into one of the most intensive scientific efforts ever undertaken in these forests, one that would cover more than a decade and span the entire coast redwood and giant sequoia ranges.

The scientific partnership supporting the initiative was equally impressive, teaming League scientists and field personnel with researchers from Cal Poly Humboldt, University of California, Berkeley, NatureServe, United States Geological Survey, and Colorado State University.

For the initial study, scientists tracked 16 permanent, old-growth plots over time to gauge their response to the changing climate, developing techniques to analyze redwood tree rings, as well as new mathematical formulas for estimating carbon storage or aboveground biomass.

ALLIES IN THE FIGHT

Thus far, in dozens of peer-reviewed published papers, presentations, lectures, and on-the-ground observations, a picture is emerging of the coast redwoods and giant sequoias playing an important role in the natural and working lands segment of California’s climate adaptation strategy. At the same time, we can see that climate-driven factors such as drought, wildfire, and extreme storms pose an existential threat to these forests.

“Redwoods are our allies in decisive climate action” says Joanna Nelson, the League’s director of science and conservation planning. “But they’ll need our help overcoming climate challenges. Instead of accepting ever-escalating threats, we need to join all our partners in climate solutions so that redwood forests, a fabric of California ecosystems, continue as a source of rich biodiversity, peace, beauty, and effective carbon storage.”

RCCI researchers found that old-growth coast redwoods store more aboveground carbon per acre than any other forest type on Earth—followed closely by giant sequoias. Cal Poly Humboldt Professor Steve Sillett and his team have found that there can be up to 890 metric tons of aboveground carbon stored per acre of old-growth coast redwood forest, which is the estimated equivalent of carbon emitted by average passenger vehicles driving 8.3 million miles.

Further, Sillett found that mature second-growth coast redwood forests, with trees as young as 150 years old, still store carbon at a higher rate than nearly all other forest types on the planet, accumulating as much as 339 metric tons of carbon per acre. This means that the restoration of these young redwood forests can pay massive climate dividends within a human lifetime. This exceptional carbon storage capacity fits right into the California Climate Adaptation Strategy, which prioritizes climate-smart management of the state’s natural and working lands to store aboveground and belowground carbon. This approach is also a foundational rationale for California’s 30×30 initiative, established in October 2020 by an executive order from Gov. Gavin Newsom. The initiative commits the state to the goal of conserving 30% of our lands and coastal waters by 2030, specifically making biodiversity conservation a priority of his administration and elevating the role of nature in the fight against climate change.

“Conserving nature is a key part of combating climate change and protecting life across the world,” says California Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot. “California is leading the way through 30×30 by protecting more natural areas in ways that expand outdoor access and strengthen tribal partnerships.”

California’s 30×30 initiative is mirrored by the U.S. Department of Interior’s America the Beautiful Initiative.

Forest protection and restoration, particularly that of redwood forests in the name of climate mitigation and adaptation, is far from new. Over the past few years, the League has received funding for forest restoration from the state’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. But the 30×30 initiative is now adding greater urgency.

“More than 100 years ago, the effort to save the coast redwood and giant sequoia forests inspired the beginning of the conservation movement, and ever since, the redwood parks of California have been connecting people to the beauty and power of nature at its most extraordinary,” says League President and CEO Sam Hodder. “Now climate change adds another layer to that equation. We know now that if we act boldly and invest in the protection and restoration of redwood forests at scale, then it is not just about us saving the redwoods, but about the redwoods saving us.”

A CRUCIAL STRATEGY

Protecting old-growth forests as the League has historically done—most recently in Harold Richardson Redwood Reserve in Sonoma County, Cascade Creek in Santa Cruz County, and Alder Creek in the Sierra Nevada—is a critically important climate strategy.

“Keeping those big coast redwoods and giant sequoias in the ground and packing away carbon every day, every year, is a real contribution to the fight against climate change,” says Nelson. “Just let them do what they do, and we’ll all be the better for it.”

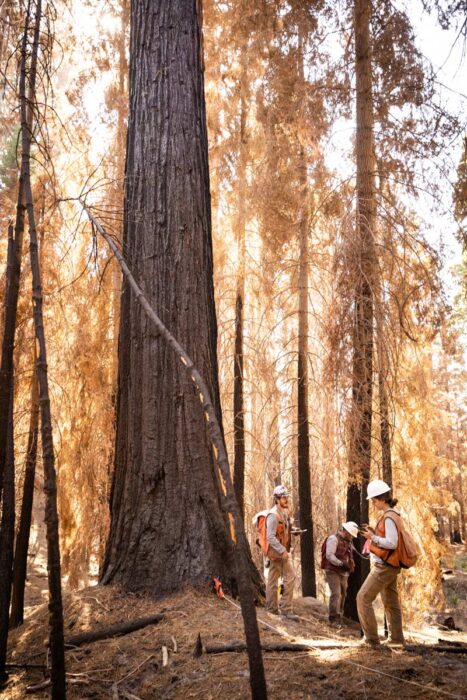

Ben Blom, who oversees the League’s restoration efforts in places such as Redwood National and State Parks and the Sierra Nevada, says that climate is increasingly a factor in the urgency and design of projects on the ground. In all instances, the goal of restoration is to set these forests back on a path to long-term health, particularly where their structure and character have been degraded by industrial logging or widespread fire suppression. Ideally, the result is not only a healthy and beautiful forest, but also a resilient one, one that can take advantage of its natural attributes to thrive in a time of drought, fire, and insect infestation.

“When we go into these formerly clear-cut forests, we look to adjacent old-growth forests as our ‘north star.’ To reach our goals, we typically need to selectively remove young trees in unnaturally dense stands so that the forest more closely resembles the species mix and spacing of old-growth forests,” says Blom. “When we do this on a project like Redwoods Rising, we can set the forest on a long-term trajectory of carbon sequestration and storage. And the forest is much less vulnerable to severe wildfire.”

Redwoods Rising is an ambitious partnership between the League, California State Parks, and the National Park Service to restore tens of thousands of acres of previously logged forest in Redwood National and State Parks.

REDWOODS NEED OUR HELP

While researchers have shown how coast redwoods and giant sequoias can be important allies in the fight against climate change, scientists from RCCI and elsewhere have also revealed warning signs of new vulnerability. Researchers have detected a decrease in summertime fog, which is important to redwoods’ growth. In addition, new research from Sillett and his team shows that the entire coast redwood range is drier due to warming temperatures, and the trees are showing decreased growth due to drought. While there has been no documented mortality in old-growth coast redwoods due to drought, trees below 40 degrees north latitude (around Arcata) showed more significant decreases in growth at the end of a four-year drought and were slower to recover to historic growth rates.

But perhaps the greatest climate-related threat that we’ve seen in recent years has been high-severity wildfire. According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, climate change is one of the key factors making wildfires bigger, more frequent, more severe, faster than ever before, and more destructive.

The California Air Resources Board estimates that the 2020 CZU Complex fires released 5.4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and while that figure includes a variety of habitat types across over 86,000 acres impacted by fire, a significant impact was in the redwoods. The fire burned through 97% of Big Basin Redwoods State Park, destroying infrastructure and surprising those who may have thought that a coast redwood forest couldn’t burn with such intensity. Coast redwoods are incredibly resilient, and the vast majority of the redwood trees in the park are alive and recovering, resprouting from their trunks and branches even in high-intensity burn areas. But a substantial amount of aboveground biomass and biodiversity was lost.

The League is now working with partners to heal the redwood forests in the Santa Cruz Mountains that were badly damaged in the 2020 CZU Lightning Complex fires and reduce the potential for another fire of this intensity. In some areas, the rapid growth of regenerative sprouts and shrubs, combined with the accumulation of downed and dead trees, could fuel more wildfire. Experts fear that repeated fires like that in 2020 could cause the redwood stands to convert to different vegetation over time.

In the Sierra Nevada, nearly 20% of the oldest, largest giant sequoias have been lost to severe wildfire.

“Climate change is deepening droughts and prolonging fire seasons,” says Nelson. “Combine the climate factors with a history of fire suppression and subsequent fuel buildup, and you get conditions for severe wildfires.”

A recent study by former League Science Director Kristen Shive noted the changing outlook for giant sequoias, observing that their legendary fire resilience is now threatened by high-severity fire. Prescribed fires are now a key part of the League’s restoration strategy in both ranges.

“If we’re going to have a future for giant sequoias, we need to go into those forests and reduce the excess fuel that helps drive these high-severity wildfires,” says Blom. “The big fear is that following these fires, you can see some of these landscapes convert permanently into another habitat type, inhospitable to the same giant sequoias that once stood there for thousands of years.”

In 2021, the League helped form the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition, which includes federal, tribal, state, and local agencies and organizations committed to protecting these incredible natural treasures from high-severity wildfire. The coalition in December announced that it had surpassed its goals, treating over 4,000 acres and replanting thousands of sequoias and other conifers. But that work is just the beginning of what is needed to restore resilience to the giant sequoia groves.

REDWOODS AS CLIMATE ACTION

As climate change becomes a bigger priority for state and federal policymakers, agencies that once made investments in conservation primarily to promote recreation and biodiversity are now greatly focused on climate, as well.

“Most of the public agencies with which we partner to complete redwood land acquisition or restoration work have questions about how our projects benefit the climate,” says Becky Bremser, the League’s director of land protection. “Thanks to projects like the Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative, we can provide answers and make a clear climate argument for the need to save these redwood forests.”

None of which is to say that the intrinsic beauty of the redwoods, that rare sense of wonder that one feels when walking through these forests, is any less of a reason to protect and restore them.

“It is critical that we continue to implement our vision to accelerate the pace and scale of conservation and restoration work in these forests,” Hodder says.

“If we make the right choices and investments today, I feel strongly that in the coming centuries, people will walk through these forests with the deep appreciation that these trees have not only restored our sense of self and our connection with nature, but have played—and continue to play—a critical role in restoring resilience to our region and inspiring a global transformation in the stewardship of our forests.”

2 Responses to “Helping redwoods fight climate change”

Carole L Burger

About 3 years ago, we bought a small property on an island in Puget Sound. There are several Coast redwoods on the island including one on our property. Ours is a young tree, but quite massive, difficult to guess its exact age. It has other evergreens around it help to stabilize the roots. Each summer I give it some water with a soaker hose and also spray branches as high as my water pressure will reach, but summertime has been dry here the past few years and I think my efforts might be a drop in the bucket; branches still turn dry and fall off. I don’t know how best to help my tree. Is it doomed?

pete mandeville

You need to make all these articles shareable, so we can spread the word to others !!