Everyone, including disabled people, deserves easier access to natural spaces

How do we value a tree body? By the board feet of wood they supply; the number of other species they support; their age, size, height? How do we value a human body? By the number of hours it can work in a day; the educational achievements it attains; the way it conforms to a standard of beauty? The ways in which colonialism and ableism assign value to animal, plant, and human bodies are the same. This is often replicated in conservation and is in fact intertwined with the creation of the conservation movement. Species must demonstrate their value to be worthy of protecting.

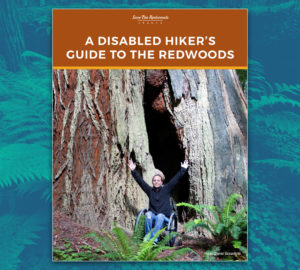

My disabled body is deemed by society to be less worthy than non-disabled bodies. I wouldn’t have to fight so hard for access to the same spaces, places, and opportunities that non-disabled people have if my body and mind were valued in the same way. Everyone has access needs, whether they are disabled or not. Even in the redwood parks, which are often called the greatest forests on Earth, I have to constantly be aware of how I access and interact with the place. Because of my disabilities, I need features including benches, water fountains, designated parking, smooth trails with few obstacles, and good information so I can plan accordingly.

Fortunately, this awareness makes me much more mindful and respectful of a place. The awareness that I have cultivated as a disabled person helps me notice many of the small things that other hikers often miss: the way that birdsong carries through the forest, how the mist shapes itself around the trees, how the light changes as it filters through upper branches and low understory. I pay attention to the way every footstep lands on the ground in an effort to maintain my balance; I notice how the earth feels under my feet and how my steps make an impact. I can appreciate an entire world within a short distance.

The redwood forests certainly offer a lush world to experience. The first time I met a redwood forest was almost by accident. I grew up in Florida and then spent several years in the southern Appalachian Mountains before moving to California. The forests of the Pacific Northwest were completely new to me, and I was in awe as I drove the coastal highway through Northern California. I have to take frequent breaks on road trips, so I pulled over at a gravel parking area off the road and got out of the car. I eyed the tall trees that surrounded me, wondering who they were as I stretched. I noticed a small footpath leading into the forest and decided a short walk might do me some good. After a few steps into the forest, the road noise faded away, and all I could sense was stillness. I realized then that these must be the redwoods that I had only read about. The redwoods towered above me with mist clinging to their branches–I had never seen trees so tall before, and I felt dizzy for a moment as I gazed upwards. My body relaxed for the first time in weeks, the tightly coiled pain around my muscles and joints releasing for a moment as I leaned against a strong and ancient tree. The trees seemed to have such a stately presence–existing exactly as they are, simply because they always have.

Disabled people also exist exactly as they are, simply because they always have. There is nothing inherently unusual or unique about disability, though the conditions of our climate and society do have an impact, just as they do on the redwoods. I don’t want the redwoods to be something that people only read about, but for so many disabled folks, that is the only way they can experience them. Lack of accessible infrastructure, limited information, and a culture of exclusion in the outdoors prevents so many people from connecting with natural spaces–places that they may find they have more in common with than they thought.

We can all unite in fighting for these places, because we all exist interdependently with one another, not because one place has more value than another. The threats to these ancient forests also threaten the lives of people with disabilities and chronic illness. We are all connected, we all deserve to exist, and we all deserve respectful access to the natural spaces of our world.

4 Responses to “Let’s Make Redwoods Reachable”

Vivian Selecman

Unfortunately, making wild areas accessible also makes them less wild. Yes, there should be benches and smooth paths in some of the parks, in some places. But remote areas are destroyed by access to multiple people. Witness what happened to Yosemite when they built the freeway into the area. I remember when they wanted to make what is now the Avenue of the Giants the path for the freeway into the Redwood area! Fortunately saner heads prevailed.

Doris Illes

Thank you for reminding us that the experience of redwoods transcends all limitations. I have experienced the redwoods in health and in a disabled capacity and the joy satisfies in both conditions. Keep up the good fight for all to appreciate.

JERRY SCHROEDER

I had my stroke in 2007-I have right side impairment and very bad balance—I have always wanted to visit the redwoods, but I would have to use a walker, and only if the trail was smooth! Is there any area that would be suitable for me? I do drive, how close can i get to the redwoods by car? feel free to email me!–thks!

Bob Miller

I’m a nature lover who was also a professional photographer. I’m now 71 and have arthritis. I can still walk, BUT, I need benches on which to rest my knees. After being mobile for most of my life, it IS frustrating not to be able to hike in many places. I now volunteer at Armstrong Redwoods in Guerneville. One of the benefits of this small, but great park is that the trails are well maintained and there are a number of benches along the way. It allows me the freedom to explore at my own pace. I volunteer in the visitor center and when people ask me about accessibility, I tell them of my own abilities and restrictions. I couldn’t agree more with the author that even a few minutes, sitting among the giants, my blood pressure drops and I forget, even if just for a few minutes, all the crap that’s going on in the world. thanks for the article.