As climate changes, we may see large shifts in the snowpack each winter. Researchers studying when snow begins to melt in the Sierra have observed that peak snowmelt is occurring 0.6 days earlier every decade in California, according to the study by Sarah Kapnick and Alex Hall, “Observed Climate-Snowpack Relationships in California and Their Implications for the Future,” published in the December 11, 2009, Journal of Climate.

This means that snow begins supplying water to the streams and river systems earlier than before and drains the Sierra of water earlier in the season. So far, this acceleration has only sped up snowmelt by a few days over the past century, but temperatures are predicted to increase in California by 2-7°C by the year 2100, according to the study by Katharine Hayhoe and colleagues, “Emissions Pathways, Climate Change, and Impacts on California,” published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2004. This extreme warming is projected to cause earlier snowmelt by 6-21 days, according to Kapnick, and reduce the total snowpack by 30% at best and up to 90% at worst this century, according to Hayhoe.

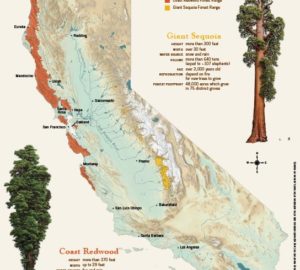

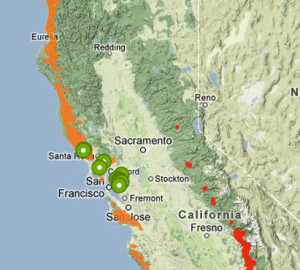

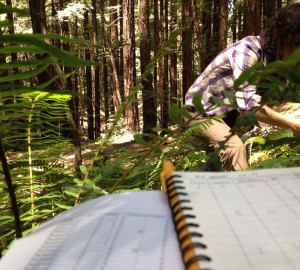

The scientists of the Save the Redwoods League Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative are working to gain the critical data necessary to develop strategies for helping redwoods adapt to such rapid environmental changes. Possible ways the Initiative findings could help redwoods survive in the future include protecting cooler and moister habitats so the trees will have a place to grow if their current range becomes too warm or dry.

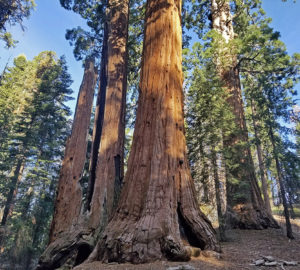

Notes on cover photo:

Nearly snowless giant sequoias at Sequoia National Park in March.

![Brachypodium sylvaticum. Photo by Kristian Peters -- Fabelfroh 11:41, 11 October 2007 (UTC) (photographed by Kristian Peters) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.savetheredwoods.org/wp-content/uploads/Brachypodium_sylvaticum.jpeg-300x270.jpeg)

![Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument. Photo by National Park Service Digital Image Archives [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.savetheredwoods.org/wp-content/uploads/Florissant_Fossil_Beds_National_Monument_PA272516-300x270.jpg)

![By Scott D. Sullivan This image has been released for use worldwide under the licensing specified below. If you require different licensing (e.g., for commercial publishing), or a larger or higher quality version of this image, it may be available from the author. You can contact the author by clicking here and leaving a message. Further, if you use this image in any works of your own the author would appreciate an email. This is by no means required, but very much appreciated. :-) (Own work) [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.savetheredwoods.org/wp-content/uploads/512px-Yurok-Plank-house2-300x270.jpg)

![Lunularia cruciata. Photo by Jon Richfield (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.savetheredwoods.org/wp-content/uploads/Lunularia_cruciata_IMG_5952-300x270.jpg)

![Big Basin Redwoods State Park. Photo by Milton Taam (IMG_0164) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.savetheredwoods.org/wp-content/uploads/Sequoia_sempervirens_sprouts_Big_Basin_Redwoods_State_Park-300x270.jpg)