It was a beautiful day for a hike along Peters Creek. The ancient forest of the Santa Cruz Mountains was in full bloom; chattering woodpeckers, the tumbling creek, giant redwood and Douglas fir trees all begged for acknowledgement and appreciation. Normally, I would have been only too happy to wander, gazing about, drinking in the vibrance and beauty of spring in full. Instead, I found myself in the strange position of shuffling along, head down, squinting at the forbs and shrubs on the side of the trail, trying to find a plant I had seen only once before (ten minutes ago, next to the Portola State Park visitors’ center). A park botanist had suggested that the area might be home to a rare plant with the unfortunate name of the Dudley’s lousewort, and mentioned that it was normally found along road and trail cut-banks in old-growth forest.

A couple of interesting things about the Dudley’s lousewort:

- It is dispersed by banana slugs and ants. Attached to the plant’s seeds is a small, nutrient-rich, structure called an eliasome that is by all accounts absolutely delicious. The seeds themselves are not so tasty or nutritious, but because they are attached to the eliasome, they go with it wherever the hungry slug or ant takes them. Ants generally abandon the seed once the eliasome is eaten, but slugs eat the whole thing, and after they digest the eliasome and pass the seed, they leave it behind in their trail of slime (which accounts for it growing on vertical road-cuts!). Eliasomes are by no means unique to Dudley’s lousewort – trilliums, yellow violets, and fetid adder’s tongue are among the many plants in the redwood forest that rely on this strategy for dispersal.

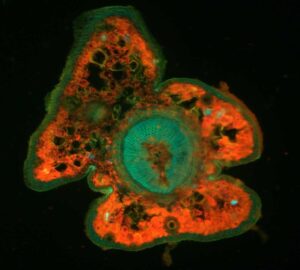

- It is a hemi-parasite. The Dudley’s lousewort cannot get the nutrition it needs from its own roots, and so attaches its roots to those of a much larger tree and siphons from them, providing the plant with essential nutrients in amounts small enough to leave the host tree unaffected.

Another interesting fact about Dudley’s lousewort, and the underlying reason why it is so hard to find, is that it requires not only closed-canopy forests, but also bare mineral soil in which its seeds may germinate and establish. A forest above with bare soil beneath is a bit of a paradox – how to get both? Of course, I realized after passing the charred cylinder of a long-burned tree, the answer is fire. Natural fires were historically quite common in the Santa Cruz Mountains (and were made even more so by the active fire management of Native American communities). With little time between events, fuel would not build up in the forest, and so the fires that occurred generally remained on the forest floor, burning brush, branches, and downed wood, and exposing the bare soil required by many plants, including Dudley’s lousewort. In the absence of fire, dead leaves and needles cover the ground, building into an organic mat too dense for the tiny seeds to penetrate. Without seeds establishing to form new plants, it is no surprise that they are so hard to find!

I didn’t find any Dudley’s lousewort that day in the woods. Maybe it’s out there somewhere and I missed it, or maybe it hasn’t been able to hold on in the absence of fire and the bare soil it creates. As we learn ever more about the forest, we find that it is far more than just its trees, and that protecting the forest means thinking about the needs of tiny plants we might never be lucky enough to see for ourselves.

Want to learn more about the redwood forest? Check out our Fun Forest Facts!