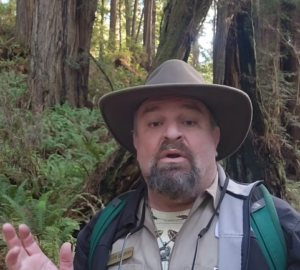

There is a sad paradox to much of my work as a forester. I became a forester because I love the forest, yet much of my work requires me to kill trees. No matter what the larger goal is for the forest, it is never an easy thing to decide to cut a tree. It’s cost me a lot of sleep over the years.

Last week was no exception. I had the opportunity to spend the day with staff at the Land Trust of Santa Cruz County (LTSCC) at their Byrne-Milliron Forest, a working forest property in the Pajaro River Valley. The Land Trust is planning a timber harvest on the forest, and we were to spend the day choosing and marking trees for harvest. The purpose of the harvest is to make the forest healthier and better able to grow — in other words, to help it once again resemble a natural forest rather than one that’s been heavily disturbed by human activity. Selective harvesting also helps protect the forest against harmful wildfire. This harvest was a light one, with less than 25% of the timber slated to be cut. With so little wood removed from the forest, the focus of our decisions was on what to leave behind.

In this part of its range, redwood grows in discrete little clumps, with ten to fifteen stems to a bunch. We marked one or two, maybe three, trees from each group, leaving the rest behind and creating space into which new trees may grow. The old-growth forest is long gone here (there are scattered residual trees throughout the harvest area that are protected as a matter of course), and the young forest that has grown in its place is made up of stump sprouts, clumps of trunks all growing from the same roots. This means that the “trees” we mark for harvest are essentially just parts of a much larger organism; we are pruning limbs rather than cutting trees.

That said, the decisions do not come easy. There are many factors that go into each choice: With the removal of this stem, how will the remaining stems respond? Will removing this stem help the rest? Is a particular stem likely to improve in quality, remain constant, or degrade over time? Does the stem provide important wildlife habitat — does it have cavities, reiterations, a flattened crown, flaking bark or basal hollows? Is it likely to develop these characteristics in the foreseeable future? Can the stem be safely felled and removed from the woods without damaging the trees or ground around it?

The LTSCC staff estimates that the forest will grow at least 25 percent more wood in the next decade than the amount of wood removed in this harvest. They plan to return in 10-15 years to a forest even more bountiful than the one we worked in last week, and will again be faced with the difficult choices of what to leave behind.

Learn more about how the League helps to restore and manage healthier forests.