Study finds surprising diversity of bees living among the redwoods

Researchers have been raising the alarm in the past decade about a global decline in insect populations, especially of important pollinators like bees. It is thought that the drivers of this population decline include habitat loss, pesticide use, climate change, and novel pathogens.

While most of the awareness around this topic focuses on the European honey bee, a species that is not native to North America and which was introduced as a pollinator of commercial crops, there are over 4,000 species of native bees that need our attention. They can range in size from smaller than a grain of rice to a cherry tomato. Around 90% of bees do not live socially in hives, rather they are solitary, building their nests in tunnels in the dirt or cavities in rocks, logs, and pithy stems. Most research on native bees in North America has taken place in open habitats like grasslands, so relatively little is known about forest bees. Given the many pressures that redwood forests face, it is of critical importance that we learn more about the bees that support the biodiversity of redwood forest plants through their pollination services.

The Pollination Ecology & Conservation lab is based out of California State University East Bay in Hayward, California. We wanted to know more about the pollinators that make a living in the redwood forests, so we visited several locations in the Santa Cruz area to see what species of pollinators we could find. At first, it seemed that there were no bees at all, until we learned where to find them. We observed that many of the smaller bees seem to cling to the undersides of redwood sorrel leaves, until a stray sunbeam illuminates their patch of forest. Warming up, they gracefully begin to stretch and awaken, eventually following the meandering paths of sunbeams across the forest floor as they drink nectar and collect pollen to provision their nests. In total, we found 14 different species of bees living in the understory of redwood forests.

In the springtime, the trademark clover leaves of redwood sorrel, an understory herb that is associated with old-growth redwood forests, blanket large portions of the forest floor in a pleasant green. These plants are so adapted to the shaded understory of the redwoods that if they are struck by an occasional direct sunbeam, their leaves close up.

Our research indicates that this plant is a critical resource to many native bees living in the redwoods. In addition to 10 bee species from several genera (Andrena, Bombus, Ceratina, Lasioglossum, Nomada, and Osmia), we also observed several butterflies visiting these flowers, including Pacific Fritillary (Boloria epithore), and some even less appreciated pollinators like bee flies Bombylius sp.

It is clear that conservation of our remaining old-growth redwood forests should take into account the varied needs of these important pollinator species, and that the presence of redwood sorrel is a boost to insect biodiversity in these forests. Our lab’s research continues as we try to identify how these pollinators support the wildflowers of the redwood forest, and what resources are important for their conservation, so that the forests can continue to show off their gorgeous springtime carpets of flowers far into the future.

2 Responses to “Pollinators of the redwood understory”

Jan Preston Dunn

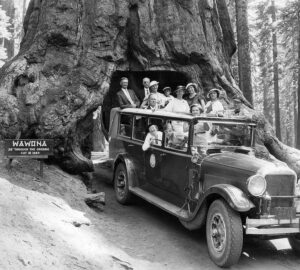

I grew up as a child going to Sequoia National Park every year with my parents who met there. Thank you for this article. I so appreciate the work you do. I recently returned to CA and visited Jebediah Smith State Park and was very aware of the sorrel growing in the understory and noticed how they move like an umbrella when hit by a beam of sunlight. I wish I had known then about the native bees that cling to the undersides of these plants. I look forward to more stories about the ecosystem that supports the redwoods, and also I love learning more about the bird, insects and plants of the canopies. I now live in Kauai. We do have some redwood trees here up in the mountains, planted by the Conservation Corps in the 30ʼs but no sorrel plants grow here, only ferns. They seem to be doing OK here up in Kokeʼe, but the bark appears darker and many are several trees which have grown together into one.

Carolyn Bishop

Beautiful insects photographed here but seeing them speared on a pin is so awful…..would love a brief view of them in situ doing their good work instead of skewered. Trivial, but valid.