The first tunnel tree was created in 1878.

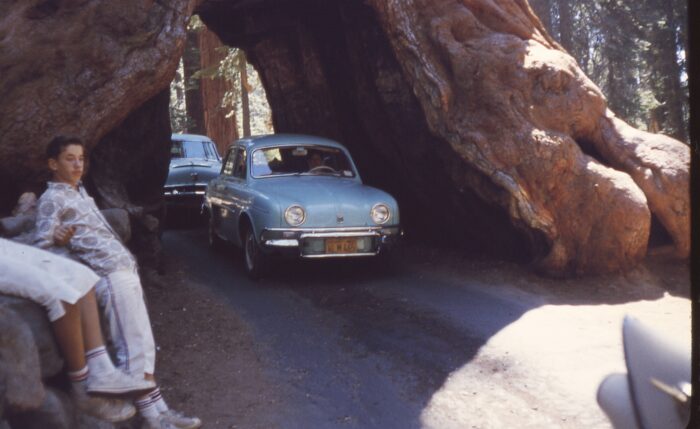

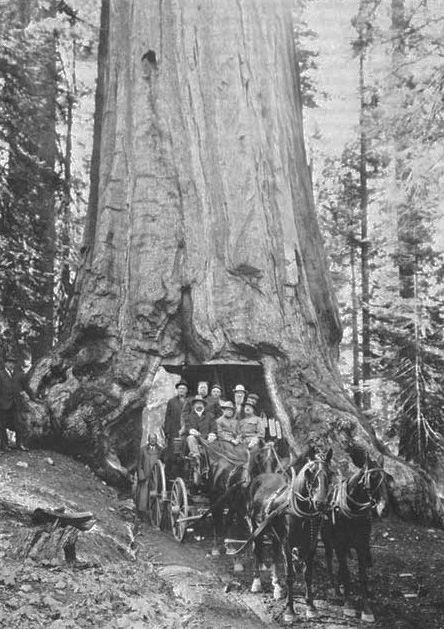

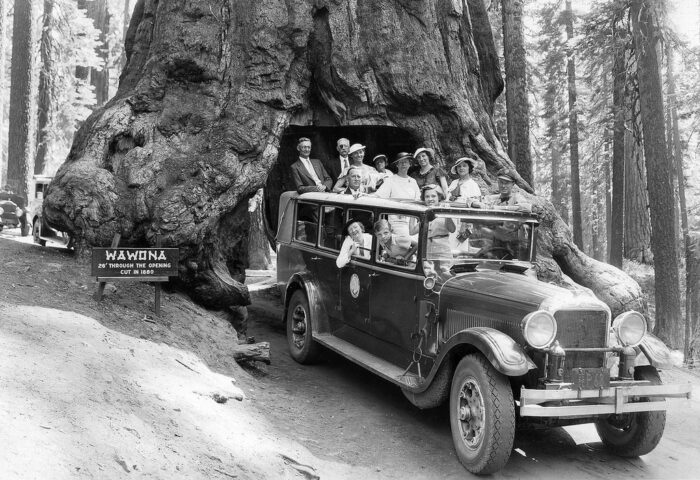

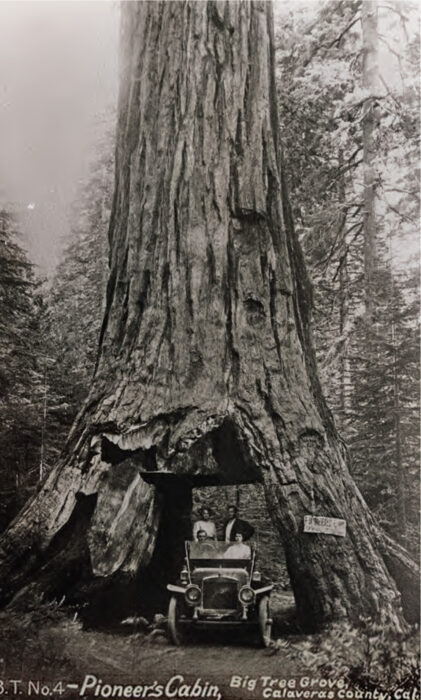

If you do any kind of search for historical photos of redwoods, the pictures you get most likely will largely fall into two categories. There will be photos of lumberjacks. And then there will be photos of people posing in and around tunnel trees. These latter photos will hail from nearly every era of photography. You’ll see sepia images of people riding horse-drawn carriages through the openings, station wagons from the 1950s, and Teslas today.

Which might prompt the question in your mind: When did this become a thing? Why did people decide that it made sense to cut these holes in trees for people to drive through?

It’s an interesting history, and one that researcher Robert Van Pelt recently explored for the League. Van Pelt is a quantitative ecologist who has performed a great deal of research as part of the Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative. But he’s also a historian who has done a lot of digging into the history of people and redwoods. He worked with us on the Pioneer’s Cabin Tree project, and in the process shared with us a lot of information about the history of tunnel trees.

According to Van Pelt, the purpose of the tunnel trees was always promotion.

“We can drive from the Bay Area to Calaveras in four hours, but back then [in the late 19th Century], it was a multi-day excursion,” he says. “So they really promoted these things to appeal to the sensationalism in the people, to get them excited about seeing these 3,000-year-old waterfalls and these giant ancient trees.”

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 created a tourism boom in the West. One of the most popular destinations was Yosemite, which people on the East Coast had been hearing about for years. Property owners hoping to take advantage of that interest created the first tunnel trees in the Sierra, in the giant sequoia range. The road to Yosemite at the time took people through Tuolumne Grove, and owners of the grove wanted to create some interest. And thus, in 1878, the first tunnel tree, now called the Dead Giant, was created there from a largely dead stump that already had giant fire caves that were easy to extend into a tunnel.

The second tunnel tree was the Wowona Tree, that promoters hoped would draw people from Yosemite to the Mariposa Grove. This tree was tremendously popular for decades, until it fell down in 1969.

The Pioneer’s Cabin Tree in what would become Calaveras Big Trees State Park was the third tunnel tree. This tree fell down in a storm in 2017. After the dust settled, California State Parks, the Calaveras Big Trees Association and Save the Redwoods League began work on an exhibit at the park, documenting the history of the tree, and what it can still teach us today. That exhibit debuted last year, and includes educational panels and what we call a “tree cookie,” which is a slice of the tree that allows you to see all the circular lines indicating growth. Turns out the tree was 1,223 years old at the time it died, and in those tree rings is a fascinating history of drought, fire, injuries, and much more.

Are the tunnels bad for the trees?

Without consulting an arborist, it’s pretty safe to say that cutting a giant car-sized hole in a tree is pretty bad for it. So the fact that many of these trees have fallen over the years isn’t that surprising. That said, it’s not so simple. Many of the tunnel trees were already heavily fire-scarred, often on both sides, so they required very little cutting to create tunnels. And some of these trees actually seem to be doing OK. Another sign of the incredible resilience of your typical coast redwood or giant sequoia.

Tunnel trees in the coast redwood range

Although they came later than their giant sequoia counterparts, there have also been tunnel trees in the coast redwood range. Probably the first was the Coolidge Tree, near Legget, and that was cut between 1910 and 1915. It didn’t last long, though. It started to tip pretty severely, so the property owners cut it down.

In the late-1930s, a tunnel was created in the so-called Chandelier Tree. And this one is actually still thriving. You can drive your car through it today. This tree is actually thriving, putting on new growth every year.

There’s also the Shrine Tree, near Humboldt Redwoods State Park. It’s still there, but not much of a tree, barely alive. And maybe the most recently created is the Tour-through Tree right off Highway 101 near the Klamath River. It was created in the 1970s and is still going strong.

It should go without saying that we’re not likely to see many new tunnel trees. Nearly all of the big giant old growth is on land controlled by California State Parks, the National Park Service, or the National Forest Service – some smaller agencies and nonprofits – and those folks are definitely not in the tunnel tree business. The ones that remain continue as a symbol of the highly-charged boosterism that surrounded the giant sequoias and coast redwoods long ago.

Special thanks to Robert Van Pelt, who provided the research for this blog post.