As we elevate diversity, equity, and inclusion at the League, we must acknowledge our full history

In a 2,000- to 3,000-year lifespan of a redwood, 100 years is a brief, yet profound moment. For second-growth redwood forests, the first 100 years represents a period of healing, growth, and resilience.

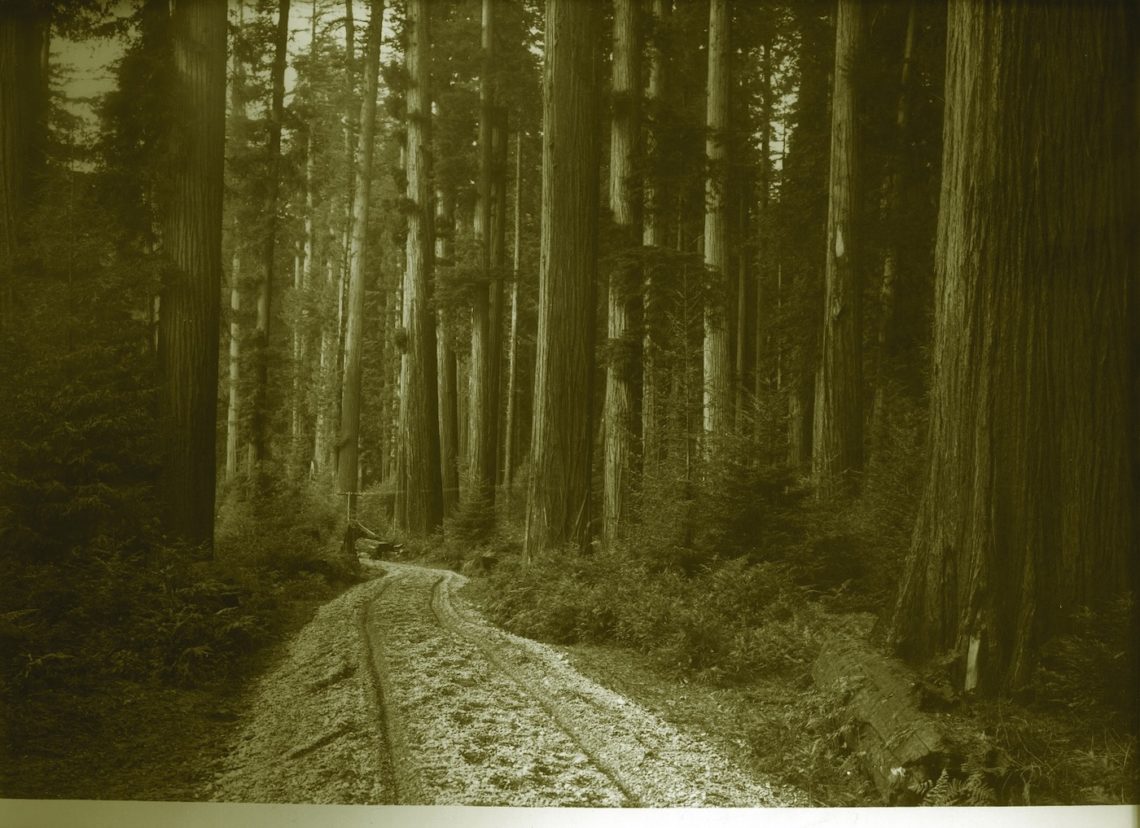

We’ve told the Save the Redwoods League creation story many times over the years: how more than a century ago, our founders John C. Merriam, Henry Fairfield Osborn, and Madison Grant took a fateful road trip up to the extraordinary Humboldt County coast redwoods to see with their own eyes vast tracts of ancient trees being harvested for timber. In the middle of a cathedral-like grove in Bull Creek Flat, just beyond the echo of axes and saws that were tearing down the redwood forests around them, they were compelled to harness their knowledge and influence to protect this magnificent forest. It is a captivating tale, one that shows the power of the redwoods to inspire connection with the natural world and to move people to action. But there’s more to this story.

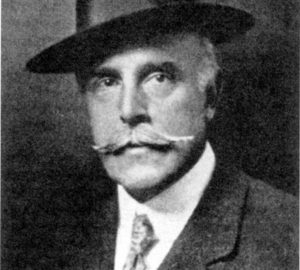

Our founders were leaders in the discriminatory and oppressive pseudoscience of eugenics in the early 20th century—around the very same time they dedicated themselves to protecting the redwood forest. In 1916, just two years before co-founding Save the Redwoods League, Grant penned the book The Passing of the Great Race, in which he warns of the decline of the Nordic race. The book was reportedly praised by the likes of Teddy Roosevelt and Adolf Hitler. It is difficult to mention those two men in the same breath, but these are the facts. Eugenics had many proponents among society’s elite back in those days, yet we will not absolve anyone’s belief in it as “normal for the time.” These dangerous concepts were used by powerful people to demonize marginalized groups and pass legislation that would dehumanize and oppress them for decades to come.

That Grant held white supremacist ideas so passionately makes it implausible that they had no influence at all in the way he approached his work, even in forest conservation. In Grant’s biography, Defending the Master Race, author Jonathan Spiro wrote, “There can be little doubt that Grant identified the redwood trees with the Nordic race. … it was that the Nordics, who in their day had conquered most of the Old World, were now making their last stand against the invading hordes of immigrants. And so too the redwoods … make their last stand against the invading hordes of loggers and developers.” To read of the redwoods being appropriated in this way is disturbing. Yet, even to this day, the discourse around conservation focuses on ecologically rich, pristine, and “superlative” nature areas.

There are many reasons why most of today’s redwood landowners, the conservation workforce, and visitors to redwood parks and public lands are white. Racial biases that have existed since the founding of this nation led to racist ideologies and policies that ultimately shaped property ownership, the conservation movement (and which lands it prioritized), and public access to protected lands. Manifest Destiny, the Indian Removal Act, Jim Crow laws, and the Immigration Act of 1924 (influenced by Grant’s book)—all of these milestones ultimately contributed to ensuring that the American landscape was for white Americans.

Equally important to note is that Native Americans across the country, including those from California tribes that were exploited during the Mission era from 1769 to 1833, live with the generational trauma that came from being forcibly removed from places that are fundamental to their identities, cultures, and histories. In many cases, the tribes were systematically eradicated by government-sponsored genocide in the years preceding and following California statehood. Today Native peoples continue to restore their relationships to their ancestral lands and their stewardship traditions, even as they fight for their land and water rights.

Historically, whenever the League has acquired a property and protected a forest, predominantly white generational landowners and redwood park visitors have directly benefited the most. While the League sees redwood forests and parks as key to our global climate resilience and essential to the well-being of our full community, we recognized many years ago the need to increase the redwoods’ relevance to underrepresented and marginalized groups in our second century. This is critical not only because conservation of our natural treasures must be inclusive and equitable to be fully realized, but also because people of color are projected to comprise the majority of the population in California and the United States within a few decades.

Over the years, journalists, authors, and academics have made the connection between the League and our founders’ involvement in eugenics. We disavowed our founders’ reprehensible beliefs internally and believed our good work would do the talking. As we at Save the Redwoods League work to bring values of diversity, equity, and inclusion into all elements of our organizational culture, we need to publicly acknowledge the reality of our own history and the misguided beliefs of our founders.

The full narrative of our nation’s history has long been swept under the rug, reinforcing a society that is fraught with injustice and institutional racism, as laid bare by the current civil rights movement that was galvanized by the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and too many more Black Americans. An honest reckoning with the past, now in this moment of national reckoning, in this moment of a new civil rights era, is critical to shaping a more inclusive future. The League and our conservation partners have an important role to play in that reckoning.

Our founders were among many early conservationists who held deeply flawed beliefs, as evidenced by recent writings from the Sierra Club and the National Audubon Society regarding John Muir and John James Audubon, respectively. We do not wish to condemn our founders or conservation leaders of the past as they did to so many, but to begin the process of healing ourselves and our communities. Transformational change is not only necessary to our collective well-being and dignity, it is also long overdue. This starts with accountability. To that end, on behalf of Save the Redwoods League, I acknowledge the abhorrent beliefs of our founders and their association with the eugenics movement; I completely disavow those beliefs; and I commit to leading our organization toward a more inclusive, equitable, and just future.

As a white, middle-class male, I have benefited from the promise of our country’s public lands, protected watersheds, clean neighborhoods, and accessible healthy foods. I have camped in forests from which Native people were violently excluded. I have been privileged with an education and financial stability that have allowed me to choose a nonprofit career doing work that I love. I am determined to parlay that privilege into work that matters for those who have been excluded from those privileges. In my seven years as President and CEO of Save the Redwoods League, I have championed a bold vision for redwoods conservation. We must apply the League’s signature ambition to how we integrate the values of diversity, equity, and inclusion into our organizational culture and conservation programs.

The League has denounced our founders’ association with eugenics through a board resolution at our annual meeting this September. We strive to build on that by elevating those who were excluded from the early conservation movement. My colleague Nina S. Roberts, PhD, of the Department of Recreation, Parks & Tourism at San Francisco State University wrote in an article recently published in the journal Parks Stewardship Forum,

“… people of color have been immersed in the outdoors/nature for centuries. From living outdoors, working in nature and fearing the woods, to playing, exploring, and loving nature (and more), people from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds have been doing it. We are out there; always have been.” Black people, Indigenous peoples, people of color, immigrants, people with disabilities, and the LGBTQ community, among many more marginalized groups, are all essential voices in the conservation movement.”

While many environmental organizations have been making progress in diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts for years, our community is at a turning point. As we forge a new “league” of agency partners, tribal partners, NGO partners, community-based organizations, and the Californians that we serve, we all have an opportunity to reimagine what conservation looks like for current and future generations. Like the second-growth redwood forest that sprouted from the very same roots of the ancient trees, together we can grow back stronger and more resilient than ever before.

39 Responses to “Reckoning with the League Founders’ Eugenics Past”

Tracey Nelson

Incredibly powerful letter and thank you for having the courage to not only write it but also post it on your website. Especially as all of our fates hang in the balance if a particular presidential candidate gets his way. Especially on the heels of the undoing of so much course correction with Project 2025. Let good for the environment not be a benefit for some and a residual benefit for all. The redwoods have taught us the power of interconnecting our roots and supporting its community without exclusion. Let the next rings on the redwood trees indicate Rings of Justice and Equality and not bigotry, racism, eugenics and fear.

Glenn Walker

To me, skin color has about the same significance as hair color or eye color. Humans are humans, and that’s how each person should be treated. Terminology recently appearing on the League’s web site seem more than out of place. It saddens me that what should be a politically neutral organization like the Save the Redwoods League has chosen to support a political organization like Black Lives Matter, and especially in a way that injects political ideology into a pristine sanctuary like the California Redwoods. Just terms like ‘Black Lives Matter’, ‘institutional racism’, ‘racial bias’, ‘white privilege’, and ‘George Floyd’ funnel into political rhetoric and have no place on the web site of the Save the Redwoods League.

I signed up to support an organization whose sole purpose is to simply protect the Redwoods for the enjoyment of everyone. For me, the Redwoods have been a special place of peace without regard to identity politics, and I feel that sanctity has been violated with recent posts on your site. Those who feel guilty for their heritage ought to wake up to the fact that you can’t weigh centuries-old social institutions on the scale of today’s norms and values. The turn down this road by the League, I believe, will forever change its direction and mission.

My hope is that the League will continue focusing on preserving the Redwoods as the sanctuary it was meant to be — free of the divisive identity rhetoric that has already divided the rest of society. And it all starts with pride of who we are today, not with the guilt of how our ancestors behaved in the past and judged by today’s norms.

Elliot Helman

I can imagine that this was a pretty painful piece to write & I really applaud those who wrote it & made the decision to put it into the e-newsletter. I also appreciate the fact that the League is taking action steps towards redressing some of the past wrongs & trying to undo the complicated history of white supremacy that we all have inherited as americans, such as the recent projects of partnering with people of color led orgs (I found the partnership with the Yurok nation in reintroducing condors into their traditional lands to be particularly innovative & inspiring). As if preserving landscapes and habitats isn’t challenging enough, the League is also doing the hard work of undoing racism within its own DNA. Admirable works & makes me proud to be a contributor, in my small way.

Tom Nguyen

Every day, we get to learn so much from the redwoods that Save the Redwoods League has protected. So thank you Sam and team for sharing this important lesson, too. And thanks to the courageous folks like the Black Lives Matter protesters that have catalyzed this progress.

Whenever I stand underneath the towering heights of our Redwoods in awe, I’m reminded not that I’m small, but that I’m one part of a world that’s much, much bigger than I am alone. I relearn that we’re all connected and interdependent.

We learn from mistakes, too — when we don’t ignore them. And I learned a lot from Sam’s letter. Thanks for highlighting and acknowledging the racist mistakes of our not-distant history so that we can make things better. Prouder than ever to be a supporter of Save the Redwoods League as it protects our shared natural treasures, truly, for all.

Steve Tognini

The path is still before us. Your first steps Sam are a reassuring beginning. Bad people can do good things, but, we have a lot of bad history to atone for.

Michael Childs

Although I doubt the League of today has any obligation to disavow the sins of its founders, long dead and gone, or even to proclaim any privilege of its current leaders, doing so may ease the consciences of some people and skepticisms of others. I doubt that there is any connection between the founders’ or leaders’ sins and the conservation of big trees (or birds or valleys) or conservation in general, but clearly it is in everyone’s interests to have the virtues of conservation and inherent values of the redwoods themselves enjoyed, taken in and appreciated by as diverse and numerous a population as possible. That is good for the League and the trees, and it is good for the wellbeing and futures of the diverse individuals who understand and value both League and trees. As the League owns up to the sins of its founders, I hope the League will not bury their names and accomplishments, as some groups are (unfortunately) doing, and will honor their hard work and foresight as it continues to protect and pronounce their legacy.

Bruce Bury

The earlier racist views of some founders of the save-the-Redwood League were living in own bubble. Recent evidence indicates that the “grand” Norse bloodline was not that pure or unique. The Vikings have been built up to be these warring heroes, but fought among themselves. Many were isolated tribes. Moreover, not some super race. They had other genetic compositions. They were a mixed lot as well… Do not believe me? Well, just published in major journal NATURE: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/09/200916113544.htm

Wayne Crafton

Right on! Power to “all” the people.

C. Johnson

More of this! Between the corona virus, George Floyd (and all who came before and after him), unemployment, sheltering in place, and the wildfires – now is the time while we have the time to see and acknowledge our systematic racism for what it is, and to join the protests to move towards an inclusive future for our country as a whole, and to expand to all the experience of our inspiring, beautiful redwoods Sam, you have laid bare our souls and that is a humbling step. Keep up the good work.

Andrea R Tracey

Wow! I’m impressed by your courage in addressing a sensitive and unpopular subject. Thank you. Your honesty is refreshing and much appreciated. Let us all move forward together with a new sense of understanding and appreciation for each other and the earth. Let us remember that humans are not the only species. Namaste

CHARLES ADELBERT ISHAM

I guess it had to happen in this day of “cancel culture.” Where do you get this stuff that only white people enjoy the redwoods and only white people owned the land. Most disappointed in the theme of this article. One of the objectives of the League that I most appreciate is the efforts of the League to encourage folks from the inner city to visit and enjoy the redwoods. Let’s continue in this manner rather than the “politically correct.”

Matthias Blume

Thank you for tackling this difficult topic. Certainly Madison Grant’s repugnant views should not be held against today’s Save the Redwoods League. The popularity of Grant’s book declined in the US in the 1930s as “the message was anti-democratic and anti-Christian, which did not sit well with the patriotic public, and hereditarianism ran counter to the belief in education, hard work, and pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps.” People figured out that it was un-American back then. I learned from your post and find some hope in this history!

Rondal Snodgrass

I was initially shocked with such a part of the League’s history, and then found remarkable admiration for Sam’s writing, a true expression of honesty and humility. It reminds me of some biblical writing that goes like this, my edits included: If we confess our sins, our Creator will forgive us as the child should not bear the inequities of the father. The new goals of SRL have embraced recovery and restoration and here is the chance to do just that. The board made a statement being clear, and the organization gets creative, goes forward to be ever more diverse and inclusive. Congratulations and well done!

Joshua Lowell

Only time will tell how well this bold acknowledgement of the racist goals of the founders will translate into the action required to repair a measure of the damage done to the people who actually shouldered the burden of hand-building this nation, in all of it’s richness, without reward or regard.

Jaime

Thank you for writing this. So thoughtful and well said!

Barclay Whitaker

I have lived long enough to see that we all misinterpret history, science and religion to our own wrong and sometimes evil beliefs. My hope is that we can honor the good and redress the wrong and evil. If nothing else, 2020 is an example of short term solutions coming home to bite us. I see the preservation of the redwoods as a long term good.

Doug Wescott

Thank you for an honest, thorough explanation of a difficult subject. I commend you for telling the true and complete history. Hopefully this will put to rest any such objections to saving the incredible and unique Redwood Forest.

Kim Baer

Tough subject to take on, Sam. Good on you for taking the first steps!

Micah Lubensky

Thanks for this. I look forward to hearing more reports of Save The Redwoods partnering with groups like Outdoor Afro and Latino Outdoors for programming.

Lowell Dodge

Sam – I applaud your statement today completely disavowing the white supremacist beliefs of the League’s founders. The statement is a clear, forceful declaration, eloquently set in the wider context of both history and recent events. However, is the League’s reckoning complete? What will happen with Founders’ Grove, honoring those whose beliefs the League repudiates? Can we heal ourselves and our communities without renaming and repurposing the Grove? Can we effectively eliminate what will now for many be the appearance of honoring not only the founders, but, by association, also their now-more-broadly-publicized racist beliefs? Will “recontextualizing” the grove by re-casting its signage and re-wording the League’s website be sufficient? These are not easy questions and I don’t pretend to have answers. But I trust the League is addressing them.

-Lowell Dodge

Kari Chao

Courageously and well said. Thank you.

Cynthia jackson

2020, for all its challenges, has offered opportunities for heart spoken words of intention.

Thank you for yours and the Board’s.

Thank you

C A Hewitt

Keep this charity out of politics!… those without sin can cast the first stone. Stop this cancel culture and remember people, as I hope they remember you, for the more good things you did in your life.

Kate O'Neill

Thank you for sharing this history with us, as painful as it is. It makes me proud to support an organization that not only does the noble work of defending the magnificent Redwoods, but is willing, as well, to be open, honest, and transparent. .

Shirley Vernale

Mr Hodder, you are a true leader, environmentalist and so brave. To approach this subject is so difficult at this time. You did an amazing job of writing and in doing so began the difficult but important steps we all need to take to heal injustice. Its people like you that will move us forward to empathy and compassion for all. Thank you so much for clearing the way for a stronger League! For the trees! For the people!

Bonnie Hazarabedian

Eloquent and so well-written. Thanks for putting this out there.

Bruce Jensen

Yes. So right. The embrace of the redwoods, and Nature in general, needs to be for the whole world, not just a tiny fraction of it.

Bruce Bury

Thank you for airing this early history of the Save the Redwoods League. There was some arrogance involved in 1920s because Native Americans were present in redwood region some 12,000 yrs earlier than now. Then Spanish and Mexican ruled up to ca 1850 covering some 150 yrs. These early founders of the League were there only some 70 yrs since California statehood. It was the reverse: they were visitors to a new land. Either way, we need to move forward and encourage all to visit the magnificent redwood stands.

Christine Meleg

Look at my last name. Most can’t pronounce it, yet I am as much a citizen as any Jones or Smith. My grandfathers in their time were victims of repression and discrimination here and in our ancestral homeland. Those times are still within memory. Some of the traditions stay with us, does this make the discrimination or repression acceptable, no. It is now a fact of history that must be never forgotten but always improved upon. Let me ask this audience this question, why are the bagpipes played at the funerals of firefighters and peace officers? Because in the 1800’s and early 1900’s those jobs were relegated to immigrants, especially Irish. Remember these words, Irish Need Not Apply. Employment as a police officer or firefighter was beneath the White Anglo-Saxon Protestants, good enough for those filthy immigrants, who played the fiddle or those noisy bagpipes. Good enough for them. not a fit job for a gentleman of high status No! Those mores are no longer anymore than a woman was required to wear a hat, gloves, corsets, long dresses and high heeled shoes escorted by a man wherever she went. Some of those things persist. Bagpipes are played at funerals, but peace officers, firefighters are respected, long dresses are for special occasions. The rest are part of the past where they belong, passed by, by more sentient thinking. Learn from the past so we don’t repeat its mistakes. Listen to the bagpipes with their mournful wails. Time to move on.

Cynthia Leslie-Bole

Long overdue, but refreshingly candid and well-written. Makes me feel good to be a part of this organization. Now let the real work continue to make our redwoods available to tribes and people of color so that they, too, can heal in the embrace of our wise and ancient sentinels.

Mike Brinkley

Thank you for this confession Sam. The Sierra Club and Audubon Society, of which I am a member have also publicly denounced the beliefs of John Muir John James Audubon. I might add that perhaps the leading eugenicist of these times was David Jordan, the founder of Stanford University. I am not aware that the University has yet come to terms with that sordid part of their history. Hopefully they will follow your leadership and do so.

Tara Shepersky

Thank you, Sam, and thank you SRL, for publicly embracing justice & the opportunity for reconciliation, and for committing to an inclusive future for conservation.

Bruce Gordon

I was just as surprised to read this as I was to read the same about Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir. The present is built on a lot of bronze giants who had clay feet We need to find new, solid footings, and this action is a good start.

Kathleen Diefenbach

Thank you so much for this important post.

Claire S. Perricelli

Well done. I have long believed we would never change ourselves or our future until we acknowledge the truth about our past. Thank you.

TV

Reading this goes to my core. I recall the deep confusion I had a fews ago when I first learned of the eugenics connection to SRL’s history, and how I struggled trying to understand just how a collective group of intelligent people could possibly recognize the majesty of a redwood tree, yet, at the same time, work so hard to harm another human being. My dear God, why??

Thank you, SRL, you cannot comprehend what I am personally feeling right now. The Truth reveals and heals.

Linda Akkerman

Thank you for being brave enough to publish this. You make me proud to be part of this community.

Jesse Schwartzman

Sam Hodder’s post today (09/15/20) “Reckoning With the League Founders’ Eugenics Past” was bold, brave and commendable. It was gutsy, certainly a difficult piece to write. As the Redwoods stand tall, so does Mr. Hodder.

Nan Jorgensen

Good for you!