As California seeks more effective ways to address the climate crisis, the pioneering Redwoods Rising partnership shows how redwood forest restoration could be a major strategy in moving toward a solution.

Coast redwood forests are supposed to be awe-inspiring and humbling. Think massive trees, seemingly forged from mythology and thrust from the ground like fortresses reaching endlessly to the sky. You want cool damp air, lush green ferns, sunlight streaming through like spotlights, and the echoes of bugling Roosevelt elks and whistling ospreys.

But here in the Lower Prairie Creek area of Redwood National and State Parks… well, this isn’t that.

“This is a ‘Hansel and Gretel’ forest,” says Rosalind Litzky, Restoration Project Manager with Save the Redwoods League. “It’s dark, the ground is bare, and it’s quiet—wildlife isn’t drawn to it.”

And the trees clearly aren’t doing what redwoods are supposed to do. “You can see they’re bunched together with skinny trunks reaching up to compete with their neighbors for a little bit of sun,” Litzky explains. Another thing these spindly trees aren’t doing well is storing carbon or providing habitat; they’re not coming close to their potential.

Strolling through, Litzky talks about how this section of forest was clear-cut about 60 years ago before its protection as parkland and then heavily reseeded. The result is an unnaturally dense forest with trees so close together that they struggle for light, water, and nutrients. The canopy is like an umbrella, with no openings for the sun to reach other plants, so the ground is largely bare. Making matters worse are historical logging roads that fragment the forest. Rain deposits sediment from these roads into the rivers and streams, burying the gravel beds that imperiled salmon need for spawning. And the density of some forests in the region makes them particularly susceptible to severe wildfires.

“Left on its own, this forest might never recover from the damage of historical logging operations. But we’re setting it on a better path,” Litzky says.

A new trajectory for young forests

The work to set forests on a new path is part of Forever Forest: The Campaign for the Redwoods, a comprehensive campaign that the League launched in January to support our ambitious vision for the next century of redwoods conservation. A major part of our vision is healing these damaged forests and restoring their scale and grandeur along the California coast and in the Sierra Nevada. And the vanguard of this vision is Redwoods Rising, a partnership including the League, California State Parks, and the National Park Service that seeks to restore second-growth forest in the Lower Prairie Creek and nearby Mill Creek watersheds. All told, the plan is to restore 70,000 acres of previously logged forests and reconnect 40,000 remaining acres of old-growth redwood forests in Redwood National and State Parks.

Without a doubt, regenerating these forests is going to be great for the trees, but it’s also going to inject new energy into the Northern California economy. And this will be particularly valuable as the state begins to emerge from the economic slowdown associated with the coronavirus outbreak. Forest workers, including those working on restoration projects, have been considered exempt from California Governor Gavin Newsom’s stay-home order since mid-March.

Redwoods Rising’s new jobs will build a forest restoration economy that will bolster the region for years to come.

While the League purchased much of the upper Prairie Creek watershed and transferred it to the State of California in the 1920s, a good deal of the lower portion remained in commercial timber hands until 1978 when the parkland was expanded. The League negotiated the purchase of the 25,000-acre Mill Creek forest in 2002 and transferred it to public hands. These are not healthy forests—both of these areas were heavily logged before they were protected. Restoration has always been the goal with these lands. Local tribes managed these forests for thousands of years, resulting in many of the spectacular old-growth forests that we cherish today; the tribes’ influence on modern conservation is hard to overstate.

There have been a number of studies concerning how logged redwood forests can regain old-growth qualities. Perhaps the most famous was started in 1923 by Emanuel Fritz, a Professor of Forestry at the University of California, Berkeley. Until 1983, he studied what’s known as the Fritz Wonder Plot, a one-acre grove of second-growth trees along the Big River in Mendocino County. Federal and state conservation teams have conducted restoration projects in the area for years.

“Since the 1970s, park managers have been working to restore the ecological integrity of these landscapes, and it’s incredible what’s been learned,” says Steven Mietz, Superintendent of Redwood National and State Parks. “Now, Redwoods Rising is putting this knowledge to work at a scale and pace never before seen to restore the redwood forest to its prior majesty.”

All but 5 percent of California’s original 2.2 million acres of old-growth coast redwood forests fell to heavy logging in the 19th and 20th centuries. For our first 100 years, the primary goal of League and other conservation interests was focused on slowing the destruction of these legacy forests. Together we saved a lot of spectacular old-growth redwood forests, but timber harvesting kept accelerating. This has left us with about 1.5 million acres of second-growth forests surrounding small islands of old-growth trees that amount to only about 113,000 acres. That vast landscape of young redwood trees, growing up from the ancient roots of a forest millions of years old, is a restoration opportunity of extraordinary scale and importance. This is an opportunity unique to California, and now, more important than ever.

Forest Restoration as a Global Climate Priority

Back to Lower Prairie Creek: To get here you’ve probably driven on the 101—the long curving highway in the shadow of tall trees on either side. To get to this spot, amid all these spindly young redwoods, you’ve taken paved and unpaved roads, and then hiked along narrow trails. You feel like you’re in California, but also very remote California. Isolated.

In a sense, you aren’t isolated, because here in Lower Prairie Creek, there’s a kinship to other struggling forests all around the globe, such as the Amazon in Brazil and the Sumatra in Indonesia. Researchers increasingly describe the foundational role of these forests to the balance of natural ecosystems, not least because of their work as the lungs of the world, storing carbon from the atmosphere and making oxygen for us to breathe. In recent efforts to stem the pace of climate change and create a better balance in our natural systems, the climate science community has focused on protecting forests from deforestation, letting young forests grow old, and restoring cutover forests as key resources in the fight against climate change.

In 2019, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued a special report highlighting the vital role of natural landscapes, particularly forests, in tackling the challenge of climate change. As climate change breaks down the barriers between natural and human-occupied landscapes, we’re seeing even more reason to preserve and restore our forests.

“The wild must be kept wild,” says Inger Andersen, Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Program. “It is time to restore our forests, stop deforestation, invest in the management of protected areas … The better we manage nature, the better we manage human health.”

As California seeks more effective ways to address the climate crisis, state policymakers are turning to natural solutions to remove carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by increasing carbon storage in areas such as forests. According to a 2018 report commissioned by the California Air Resources Board, about 5,340 million metric tons of ecosystem carbon are stored in California’s natural and working lands (farms, ranches, etc.), of which forest and shrubland contain the vast majority at about 4,520 million metric tons. For context, it would take about 256 years for California’s 14 million passenger cars to generate this much carbon in the form of carbon dioxide. The question leaders are asking themselves now is how the state can better manage its natural landscapes to support carbon storage.

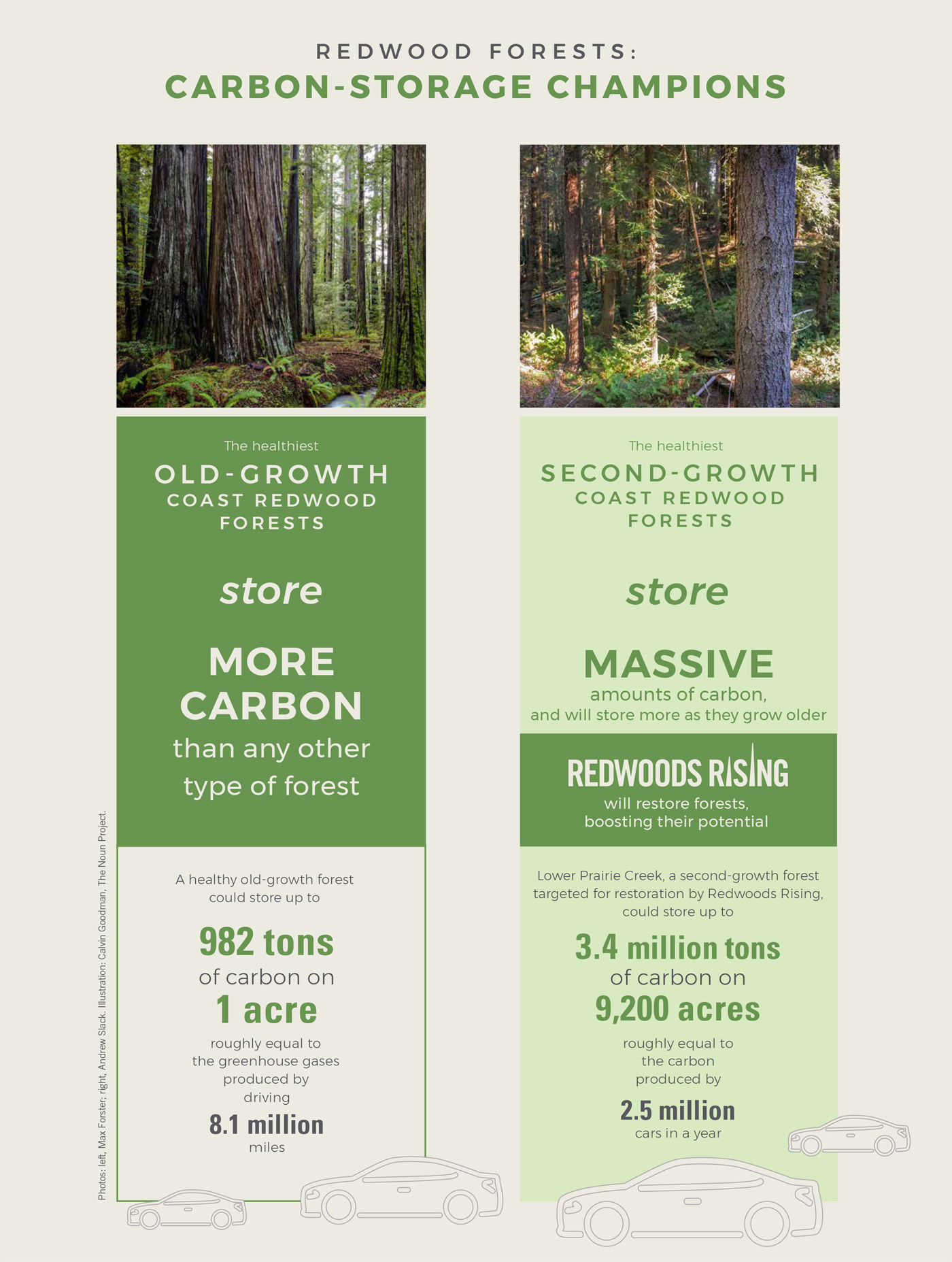

Redwoods could be a big piece of that puzzle. Scientists are studying redwoods’ carbon storage as part of the Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative, a collaborative research program of Humboldt State University, the University of Washington, and Save the Redwoods League. Researchers have found that old-growth redwood forests store more carbon than any other type of forest in the world, packing as much as 982 tons of carbon per acre—982 tons of carbon is equal to the greenhouse gases produced by driving 8.1 million passenger vehicle miles.

More importantly, recovering second-growth forests are storing massive amounts of carbon well before they reach old-growth status. Recent estimates show that the Lower Prairie Creek forest is only storing about 204 tons of carbon per acre. Mill Creek forest is storing about 108 tons per acre. The healthiest second-growth redwood forest recorded is storing 374 tons of carbon in one acre, recovering about a third the amount of carbon as old-growth forest in just 150 years—and is on its way to storing much more.

At that level of carbon storage, the 9,200 acres targeted for restoration in Lower Prairie Creek could, in time, store 3.4 million tons of carbon, the same as that produced by 2.5 million cars in a year. At this rate, taking advantage of the tremendous potential carbon storage of the 1.5 million acres of recovering second-growth forest in California could greatly bolster the state’s efforts to address climate change.

For Sam Hodder, League President and CEO, these struggling, formerly logged forests are vast forests of opportunity.

“Up in the forests of Northern California, we have the potential to bring it all together—the inspiring beauty, a new restoration economy, the state’s leadership on climate, and a way to demonstrate to others around the world how landscape-scale forest restoration can be done,” Hodder says.

Following a ribbon-cutting ceremony in Redwood National Park last fall, things are ramping up for Redwoods Rising. Most of the permits and approvals are in place, and work is to begin in earnest this summer to remove old logging roads and give trees room to grow.

“Save the Redwoods League, the National Park Service, and California State Parks have learned a lot in over a century of stewardship,” says Jay Chamberlin, Chief of California State Parks’ Natural Resources Division. “Building on our shared experience and private partnerships to restore these cherished landscapes at a scale we’ve only dreamed of before—this is what 21st-century restoration can look like, and it’s truly transformative.”

Standing in Prairie Creek, Litzky thinks of the future with hope: “Once we give it an opportunity, nature will take over, and the results will be spectacular.”

REDWOODS RISING

WHAT

Redwoods Rising is a historic partnership including Save the Redwoods League, California State Parks, and the National Park Service that will heal 70,000 acres of previously logged coast redwood forests and reconnect 40,000 remaining acres of old-growth redwood forests in Redwood National and State Parks.

WHERE

Redwood National and State Parks extend along the Northern California coast roughly between Eureka and Crescent City.

SIGNIFICANCE

Redwoods Rising will help heal the impacts of forest destruction and fragmentation, and bring back the vast old-growth redwood forests and their powerful carbon-storage capabilities.

LEARN MORE

See a video about our Redwoods Rising apprentices, the next generation of forest stewards.

DONATE

Please make an investment in the redwoods today–– your impact will last centuries. Visit our secure website.

This feature appears in the beautiful printed edition of Redwoods magazine, a showcase of redwoods conservation stories by leading scientists and writers, as well as breathtaking photos, answers to readers’ questions, and how you can help the forest.

Join our thousands of members today for only $25, and you’ll get future editions of our Redwoods magazine.