The Physiological Ecology of Bats in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, Informed by Fire Management

Climate change is increasing the intensity and frequency of wildfires, and many animal species may be at risk in this new normal. Bats are considered ecosystem indicators because they occupy a wide variety of niches and because they are very sensitive to changes in their habitat and the climate. By understanding how bats respond to wildfire, we can better help them survive as the landscape changes.

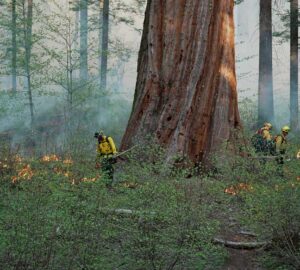

With this in mind, Anna Doty, PhD, led a study of California myotis bats in the South Fork region of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Park following the SQF Complex fire. This fire burned nearly 174,000 acres in 2020, leaving behind a patchwork of unburned and burned land, ranging in low to severe burn severity. Doty wanted to understand if the fire affected the type of roost sites bats selected, and how they coped with the higher temperatures in this altered, post-burn landscape.

Doty and her colleagues captured bats in a central location and fitted them with temperature-sensitive radio transmitters, which allowed them to continuously monitor the animals’ skin temperatures and track them to their daytime roosts.

It was thought that the California myotis preferred roosting in dead conifer snags in more open areas. But the bats in this study frequently roosted in living oak trees in denser, more “cluttered” forests, including giant sequoia groves. The bats also showed a preference for unburned areas.

What’s more, the temperature data showed that the bats frequently entered a state of temporary hibernation in the early morning hours, when it was coldest. This state, called torpor, helps the bats save energy.

These discoveries suggest that California myotis bats are flexible enough in their behavior to take advantage of the altered conditions following a fire, especially when a mix of burn severities are present

These results have important implications for conservation, Doty says. Since giant sequoia forests tend to be more fire adapted than some other forest types, they may be important for the continued survival of California myotis bats. Even though the bats don’t typically roost in giant sequoia trees themselves, they may prefer roosting in denser giant sequoia forests than in open, severely burned ones.

There is still much to learn about how bats respond to both wild and prescribed fires in California, Doty says. “Because there exist a huge variety of habitats in the state, there are practically endless opportunities to determine how different species respond to fire both in terms of their physiology and roost selection, but also foraging strategies,” she says.