Exclusion in the past influenced the redwoods movement as we know it today

Black History Month offers an opportunity to reflect on why Black voices continue to be underrepresented in conservation. The more we learn about the cultural context of the early 20th century at the advent of the conservation movement, the better we understand how the racist and classist beliefs and practices of the era created systemic impacts on conservation culture and outdoor recreation as we know it today. If we learn from this history, we can help change its course.

Women, and women’s clubs specifically, formed the backbone of the early redwoods conservation movement. They fought hard for the preservation of California’s forests, despite major pushback from timber companies, which were driving a lucrative trade, as well as government officials, who were often more inclined to listen to corporations than to women conservationists. However, when we look at the important, yet often overlooked historical contributions of women to redwoods conservation, it’s critical to also acknowledge the whole of their impact.

Most of the progressive era women’s clubs fighting for the redwoods were exclusive. Almost all were white-only, with members of high society—wives of doctors, lawyers, and business leaders—making up the bulk of membership. Many of these club members held white supremacist and xenophobic beliefs. For example, in the early 1920s, the California Federation of Women’s Clubs made great strides in their campaign to create a redwood national park, persuading the governor of California to buy and protect a large swath of redwood forest. However, at the same time, its president Adella Tuttle Schloss was promoting Americanization, a process that called on white, upper middle-class, American-born women to acculturate and “civilize” immigrant women. Furthermore, under her leadership and amidst an upswing in anti-Japanese sentiment, the Federation passed an anti-Japanese resolution.

Many of the most powerful women in the conservation and women’s suffrage movements, despite being integral to the preservation of redwood forests and securing women’s right to vote, simultaneously shut out or deliberately caused harm to lower-class women, women of color, and immigrants, leaving them excluded from a movement that could have benefited from more voices.

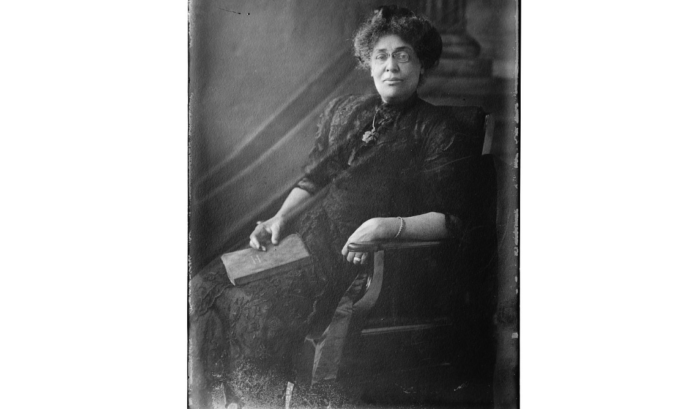

Black women’s clubs rarely received recognition for their political and environmental work, including organizing to improve sanitation in their own neighborhoods. Because of the urgency of issues close to home—issues that were rooted in institutional racism—many did not have the time nor the privilege to get involved in the redwoods movement and forest conservation at large. As Margaret Murray Washington, a prominent Black suffragist and founder of the Tuskegee Woman’s Club explained:

“The other day I was asked by one of the women if I didn’t think we ought to go into the forestry question that so many women’s clubs were taking up. I said: ‘Not at all, because most of those women have already got their own yards fixed up front and back, and have time to think about the forests. We have got to try to get shrubbery and trees and roses in our own yards first.”

When Black women did try to get involved in the work of white women’s clubs, they were often rejected. In 1902, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC) prohibited Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, a delegate for the Woman’s Era Club, an all-Black women’s club, from attending a GFWC convention. After the incident, the California chapter’s president Laura Lyon White, a prominent voice who was adamantly opposed to integration, claimed, “Those who have been so ambitious to admit colored women are fanatics and visionaries … the change in the regulations governing qualifications for membership will only result in a disruption of many clubs.” Eventually, the California Federation members ended up voting to allow Black women’s clubs to join, and White stepped down from her presidency for refusing to represent an integrated federation.

That moment of progress may have reflected a changing society, but today there is still a long way to go. Many Black women in science, conservation, and beyond continue to face similar issues to what Murray Washington highlighted. Marine biologist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson wrote in the Washington Post last year, “Even at its most benign, racism is incredibly time consuming. Black people don’t want to be protesting for our basic rights to live and breathe. We don’t want to constantly justify our existence. Racism, injustice and police brutality are awful on their own, but are additionally pernicious because of the brain power and creative hours they steal from us. … Consider the discoveries not made, the books not written, the ecosystems not protected, the art not created, the gardens not tended.”

One Response to “Why Are There Few Black Voices in Redwoods Conservation?”

Dr. Juko Holiday

Thank-you for writing this article. I am a black woman who is involved in the conservation of Redwoods via an initiative I founded called The Care Forest Project. Part of the aim is to create a micro-conservation movement that can make participation in conservation accessible to everyday people. You can read more about the work at: https://www.redwoodlove.org

I would be happy to connect. Looking at the history and legacy of conservation is critical, the next step is to support existing black conservationists in their work. We are out there, and care deeply about these trees.