Removing Klamath dams will help revive fish and tribal communities, and nourish forest ecosystems

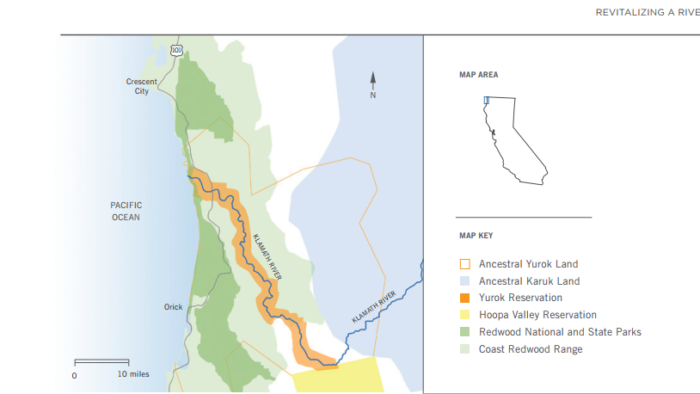

The Klamath is the second largest river in California, flowing 257 miles through Oregon and Northern California and emptying into the Pacific Ocean. There, it bisects the Yurok Reservation and Redwood National and State Parks, a World Heritage site that contains 45% of the planet’s protected ancient coast redwood forests.

For thousands of years, the Klamath hosted an abundance of anadromous fish, including spring and fall Chinook salmon, coho salmon, steelhead, Pacific lamprey, and green sturgeon. Forest ecosystems and Indigenous tribes, including the Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, and Klamath, have depended on this bounty for millennia.

But for decades, four dams on the river’s main stem have barred fish and compromised water quality, threatening the survival of native fish and the tribes. The first of these hydroelectric dams went into service in 1918, the last in 1962. The dams have no fish ladders (pools built like steps to enable fish to bypass a dam), effectively cutting fish off from more than 400 miles of river and stream habitat.

The effect of the dams is clear to Yurok Tribal member Barry McCovey Jr. and his two sons, aged 7 and 9. When they went to the Klamath River to fish last year, they barely caught any salmon.

“It was heartbreaking,” says McCovey, who is a Senior Fisheries Biologist for the Yurok Tribal Fisheries Department. “I really want them to grow up harvesting salmon. It’s so important to us to be able to eat and process these foods and give that food to elders. It’s a vital part of who we are.”

McCovey lives on the Yurok reservation near the mouth of the Klamath, but much of his efforts focus upriver, where the dams stand. Now, thanks to an agreement signed by the Yurok and Karuk Tribes, the states of California and Oregon, PacifiCorp, and the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC), removal of those dams is tantalizingly within reach. Under this agreement, announced in November 2020, PacifiCorp will relinquish ownership of the dams, and California, Oregon, and KRRC will own and operate them. KRRC will spearhead dam removal and restoration.

THREATENED SALMON

Today, the Southern Oregon/Northern California Coast (SONCC) coho salmon is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Spring and fall Chinook populations are also crashing.

“I’ve seen the numbers decline drastically in my lifetime,” says McCovey, who is 42. “The last five years have been incredibly tough on tribal members, myself included. It’s been hard for people to get enough fish to feed their families.”

Other practices are partly to blame: agriculture withdrawals, heavy logging and road building near streams; non-tribal overharvesting; and poor ocean conditions exacerbated by climate change. The Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa tribes each have robust fisheries programs and have been working hard to restore and monitor the creeks and tributaries that serve as spawning habitat.

“Dams aren’t the only issue; not by a long shot,” says Frank Myers, Vice Chairman of the Yurok Tribe. “But it’s clear that if the dams remain, none of [our restoration work] will be effective because of poor water quality and high rates of disease.”

In September 2002, huge numbers of adult Chinook salmon that had returned to the Klamath River to spawn began washing up on the banks within the Yurok reservation, victims of a parasite and bacterial pathogen.

The die-off galvanized many stakeholder groups, but especially the tribes, who viewed the unprecedented event as a stark warning.

“To watch 85,000 to 150,000 salmon lying on the banks of the river, dead, it sank in that if we didn’t do something, we could see the end of our existence,” Myers explains. “So we moved as if we had no other choice—as if our existence depended on it.”

Myers became an activist for dam removal, joining members of the Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa tribes as they traveled to Omaha, Nebraska, headquarters of Berkshire-Hathaway, which owns PacifiCorp. Direct action and involvement in regulatory processes empowered tribal members, says Myers.

“Direct action gave us a platform to fight for our lives and fight for our ancestors and children, and to help solidify a future for our people,” he says.

The impaired fish runs have direct health impacts on tribal communities, which have long depended on fish protein for sustenance.

“At the core of tribal sovereignty is food sovereignty,” says Keith Parker, a Senior Fisheries Biologist for the Yurok Tribe who is of Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, and Tolowa descent. “The Klamath Basin tribes are among the poorest and most food insecure in the country.” He adds that the loss of traditional foods correlates with increasing rates of obesity, diabetes, poor mental health, and even suicide.

The compromised runs cut tribal members off from cultural practices, too. Many mourn the loss of summer fish camps, communal events where people processed fish, reunited with friends, and passed skills and traditions to their children.

“The river is like the blood that flows through our veins,” says Parker. “We’re river people; we’re fish people. The river feeds a lot more than physical bodies. It feeds our spirits.”

BENEFITING THE FOREST

Aside from impacting fish and human health, the dams also deprive forests of much-needed nutrients, says Parker. When adult salmon return to spawn and die, animals eat them and help scatter the carcasses across the forest floor.

“All of these marine-derived nutrients are absorbed into those ecosystems,” says Parker. “It’s no accident that when you look at a map of Pacific Northwest conifer forest coverage and salmon spawning streams, they overlap.”

Dam removal is expected to improve fish runs above and below the dam sites, supporting forests, including the redwoods along the Lower Klamath and its tributaries. More habitat, improved flows, and cooler water temperatures will translate into bigger, healthier, more abundant fish. In turn, the uptick in nutrients will nourish riparian vegetation, stabilizing banks, keeping creeks cool, and attracting birds and browsers such as deer.

Deconstruction of the four dams is expected to begin in 2023. The removal has faced opposition from those who cite the release of silt buildup behind each dam. They also cite the loss of flood control, electricity, and water upstream for threatened species, firefighting, and agriculture. Proponents of the removals say the dams are antiquated and produce “very little” electricity.

Once the dams come out, there will still be much work to do. The Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, and Klamath tribes will be partners in restoring the reservoir footprints and the river downstream and upstream.

It’s a burden McCovey gladly takes on. “We call ourselves ‘fix-the-world people,’” he says, adding that the drive to balance things is interwoven into his work and his tribe’s ceremonies. Dam removal represents not just a critical step toward repairing fish runs, but also restoring relationships that have flourished for thousands of years.

“We need the river just like the fish need the river,” says McCovey. “And we need the fish, and the fish need us.”

“The river is like the blood that flows through our veins. We’re river people; we’re fish people. The river feeds a lot more than physical bodies. It feeds our spirits.”

—Keith Parker, Senior Fisheries Biologist, Yurok Tribe

REMOVAL OF KLAMATH DAMS

WHAT

The four Klamath River hydroelectric dams upriver from Redwood National and State Parks block historical fish habitat. The dams have contributed to devastating some salmon populations and the food supply of Indigenous Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, and Klamath communities.

WHEN

Dam removal and the return of the river to a free-flowing condition is expected in 2023.

RESTORATION

Klamath River Renewal Corporation and Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, and Klamath tribes will begin restoration activities immediately after removal of the dams. Work will continue for several years.

BOON TO FOREST ECOSYSTEMS

Dam removal is expected to improve fish runs above and below the dam sites. Forests benefit from the nutrients provided by salmon carcasses that animals have scattered on the ground.

This feature appears in the beautiful printed edition of Redwoods magazine, a showcase of redwoods conservation stories by leading scientists and writers, as well as breathtaking photos, and ways you can help the forest.

Join our thousands of members today for only $25, and you’ll get future editions of our Redwoods magazine.