It might not be magic, but it's still fascinating.

It’s hard to pinpoint the origin of the term “fairy ring” as it pertains to coast redwood forests, but it’s easy to see how it came about. These forests can seem like something out of storybooks – trees of unreal age and height, beams of light, moist green moss and ferns underfoot. And these unusual circular clearings, ringed by tall trees, might seem intentional, if not magical, to some.

The science behind fairy rings, also sometimes called fairy circles, might not be magical, but it is no less fascinating and unique. The clearings are a by-product of coast redwoods’ amazing reproductive nature, which is a source of their incredible resilience.

Coast redwoods reproduce in two ways. The first, unsurprisingly, is through seeds. During the wet season, the coast redwoods produce cones, which carry hundreds of thousands of seeds. These seeds are then released during the dry periods onto the forest floor, where just a tiny fraction take hold and grow into new trees.

The other way that coast redwoods reproduce is by sprouting from their extensive shallow root structure. These young sprouts get a terrific “head start” from the nutrients of the mature tree and surrounding root structure.

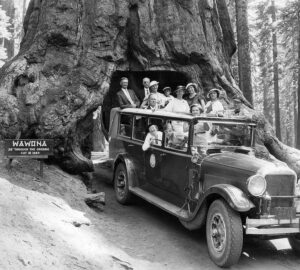

When a mature coast redwood is cut down – or falls down for some other reason, such as windthrow, or burns – its roots will commonly begin to resprout from the roots in the manner around the stump, often in a near-perfect circle. Over time, the stump will decay and disappear, leaving only the clearing with the circle of younger trees around it. And then you have a fairy circle.

It should be noted here that occasionally, clonal spread, aka fairy rings, has been documented in different shapes, such as figure-eights or chains of multiple overlapping rings.

The League’s interest in fairy circles goes beyond the aesthetic implications. For instance, we have funded studies into the genetic diversity within fairy rings to ascertain to what extent the trees in a fairy ring are clones of the original tree. These determines that as much as 10 percent of the trees were not direct clones, which has important implications for the restoration of second-growth forests.

2 Responses to “Explaining the mystery behind fairy rings in the redwoods”

Mario D Vaden

Redwoods do not reproduce “two ways” but rather THREE (3) or more ways. One is seed, a 2nd can be basal or root sprouts which can include fairy rings. A 3rd documented is layering of fallen twigs impaled in the earth. A 4th can include fallen trunks holding enough moisture for survival of tissue to where growth develops into another regular looking redwood tree that spread roots down into soil. Cheers, M. D. Vaden, Certified Arborist.

NTanya

So if the trees that grow from the roots are clones, does that mean that a tree growing in a fairy ring, that sprouted from a 2000 year old tree, has the exact same dna/genetic make up as the 2000 year old sprout?