I’ve spent much of the past week thinking about our Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative, and what our recent results mean for the future of the redwood forest. As with any good scientific research, the first phase of RCCI raised far more questions than it has answered. While the questions alone are far too numerous for as brief a forum as this, it is worth thinking about some of the major issues that this research has brought to the fore. I’ll be spending the next few weeks discussing some of the implications of our findings, and I would welcome your comments or questions as we explore this new knowledge together.

To begin with the obvious question and one that’s been implied in every article I’ve seen on the subject: is climate change good for redwoods?

It is very tempting to see two parallel trends – such as an increase in temperatures in California, and an increase in wood production in ancient redwood forests – and say that the second is caused by the first. Tempting, but not correct. In any complex system (and the interaction of climate and ecology is certainly that!), any trend is more likely due to a number of contributing factors rather than a single ‘cause.’ So, while it is certainly true that the redwoods have seen an increase in wood production over the past 50 years, we do not know what has caused that trend. It may well be that warmer temperatures are the cause of this increase, but this increase could also be due to a decrease in coastal fog over the last century or an increase in air clarity following the closure of many mills on the North Coast in recent decades, both of which would serve to increase the amount of light the trees receive (and thus the amount of photosynthesis they can perform).

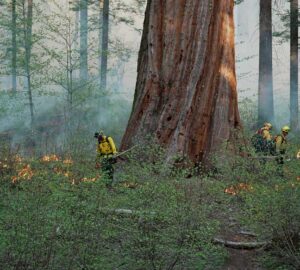

Several decades of fire suppression may also have resulted in the ancient trees retaining fuller crowns (and not having to spend energy re-growing foliage after a fire), also allowing them to photosynthesize more. Does this increased photosynthetic capacity offset the increased competition for soil nutrients and moisture due to an ever-growing understory not beaten back by periodic fires (and could the lesser increase in giant sequoia growth – in ecosystems that generally experienced more frequent fires than the coast – be related to this tradeoff)?

All this doesn’t answer the question, though. When we think about saving the redwoods, we generally think about the whole forest; the redwoods are not simply a bunch of individual trees that happen to grow next to one another. RCCI research has shown that tree growth (the amount of wood produced each year) has increased in the last half-century, but is wood production a good indicator of the health of the forest? Before we can make claims about the effects of climate change on the forest (rather than just the trees within it), we need to learn more about how the other important elements of the ecosystem are responding.

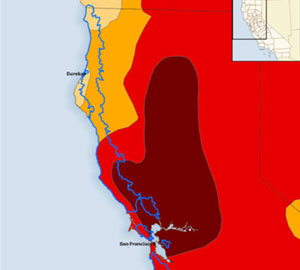

If we widen our focus beyond that of the individual trees or stands, the question reasserts itself, though on a similarly broad scale. Let’s just say that it is indeed warmer temperatures and decreasing fog that are causing individual redwood trees to add more wood each year. What does that trend mean for the whole redwood forest, from Big Sur to Oregon? Will a changing climate affect where these forests can establish and grow into the future? RCCI research has found that the climates of northern redwood forests of Humboldt and Del Norte counties have experienced less change over the past century than the central or southern regions of the redwood forest. Will these northern areas retain their stable climate, and will redwood forests be able to persist in the central and southern regions in the face of warmer, drier conditions?

There are so many more questions to be answered, and so many more still to be discovered. Each new finding will help us better understand the complex ways in which climate change is affecting the redwood forest, and will provide the scientific basis we need to answer the really important question – what do we do about it?