Ecological Basis for Old-growth Redwood Forest Restoration: 25 year assessment of redwood ecosystem response to restorative thinning

by Save the Redwoods League on

Dr. Christopher Keyes and Andrew Chittick have found that thinning—removing select trees in a second-growth coast redwood forest—speeds up the forest’s development of old-growth characteristics, which include tall and bulky trees, small gaps in the canopy through which sunlight can penetrate, trees of varying heights, thicker tree branches, understory shrubs and ferns, and healthy young saplings.

After a redwood forest has been clear cut, sunlight pours down on what used to be a relatively dark forest floor. New saplings, getting their starts at roughly the same time, initially don’t have to compete with their neighbors for sun. But as they grow taller and wider, they begin to shade one another and block almost all light from reaching the forest floor. Due to overcrowdedness, some trees grow very slowly and others die; understory plants struggle to survive. If a forest in this light-suppressed condition is left untouched, it can take hundreds of years for it to even start developing old-growth characteristics.

In an old-growth forest, natural disturbances in the form of fire, lightening, and wind create and maintain gaps in the canopy. The gaps, allowing light to hit the ground, give young saplings the chance to shoot up and provide variety in the age and physical structure of a forest’s trees. Thinning in a second growth forest is an attempt to mimic natural disturbance. It relieves the forest’s unnatural, uniform growth created by the clear cut.

Twenty five years ago, park managers thinned groups of trees in the Holter Ridge area of Redwood National Park and predicted that their careful removal of some trees would accelerate the development of old-growth characteristics. Keyes and Chittick took advantage of a rare opportunity to observe the effects of restoration-based thinning. They’ve been watching the forest develop for the last twenty five years.

Based on their observations, they suggest that best results come from thinning second-growth forests at an early age. Relative to comparable unthinned groups of trees, the thinned areas supported tree diameters nearly twice as wide, a higher percentage of living tree crowns, more understory vegetation, including shrubs, ferns, and redwood saplings, a higher diversity of understory vegetation after five years, larger redwood branches, and a more varied mix of redwood, Douglas-fir, and tanoak trees in the canopy. The added sunlight in the thinned stands should allow dominant trees to reach greater heights more quickly. This is especially important for forest organisms, such as insects, birds, salamanders, and mammals, which more frequently use large trees for their associated habitats—large snags, fallen wood, and bark fissures.

Keyes and Chittick note that if forest managers create the right initial forest structure early on and allow nature to freely disturb stands, old-growth characteristics will self-perpetuate sooner than if the stands were left alone.

Explore More Research Grants

Redwoods may offer bats a haven amid disease, rising temperatures

Bats are a top conservation priority. Not only are these fascinating mammals vulnerable to climate change, but many species around the world are also falling victim to a fungal disease called white-nose syndrome. New research funded by Save the Redwoods League suggests that coast redwood forests may offer bats refuge from both of these threats.

Programs reduce densities of birds preying on threatened marbled murrelets

Research funded by Save the Redwoods League suggests that programs designed to help reduce jay populations in areas where marbled murrelets nest, including old-growth coast redwood forests, will give these threatened seabirds a better chance at successful reproduction.

Study shows bats’ resilience after giant sequoia fire

Climate change is increasing the intensity and frequency of wildfires, and many animal species may be at risk in this new normal. Bats are considered ecosystem indicators because they occupy a wide variety of niches and because they are very …

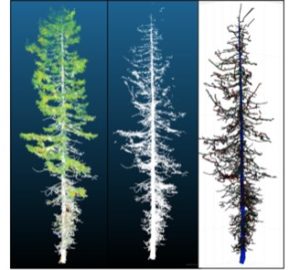

Researchers use lasers to measure local redwoods’ carbon storage

Alexander Barajas-Ritchie and Lisa Patrick Bentley, PhD, of Sonoma State University have shown that 3D models generated from light detecting and ranging (LiDAR) technology may work at providing accurate estimates for local redwood trees in Northern California.

How human encroachment changes the forest’s edge

Nanako Oba, a graduate student in the Environmental Studies Department at San Jose State University, conducted a study at the Forest of Nisene Marks State Park to investigate the edge effects on soil, trees, and understory plants in recovering second- and third-growth redwood forests

Novel Fog Research Method Could Help Predict Forests’ Drought Risk

In a paper published in January 2016, researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Oregon State University outline a new way to track clouds (and fog) over space and time.

Western Swordferns’ Water Absorption Differences Likely Due to Leaf Structure

Researchers in the Department of Integrative Biology at the University of California, Berkeley investigated foliar uptake in western swordfern, an integral species in the redwood ecosystem.

Study Suggests Fires Increase Relative Abundance of Redwoods

Researchers believe that fires burned through most redwood forests every six to twenty-five years; in other words, it was a normal occurrence. What is not normal, is the lack of wildfires in the redwood forest.

How Long It Takes for a Forest to Recover after Clear-cutting

For the sake of redwoods conservation, it’s crucial to understand the patterns of natural recovery in second-growth forests. Researchers at San Jose State University wondered how long it takes for a forest to truly recover after clear-cutting, and decided to approach the question by comparing forests in different age classes.

Mitigating Effects of Unofficial Trails on Ancient Redwood Groves

And now, because of internet and mobile technology, the locations of more and more of the tallest redwoods are becoming public knowledge, drawing more people to these giants. This often leads to people blazing their own trails either because the officially designated trail does not provide close access, or because there is no official trail to a specific tree or grove. These unofficial trails are called social trails. So, just how great is the impact of these unofficial trails?

New Practice Promising for Restoring Lost Forests of Giants

Humboldt State University and California State Parks research studies new approaches to variable-density thinning across the entire Mill Creek property. Learn more about this research.

What is Growing in the Canopies of the Tallest Trees in the World?

Recent League-supported research by Rikke Reese Naesborg looked at the epiphyte community in three coast redwood parks in the southern redwood range.

Some Coast Redwoods May Seem to Be Clones, but They’re Not

If you’ve visited a coast redwood forest, you’ve probably seen these trees growing around the stump of a logged giant. These “fairy rings,” as they’re known informally, show how the coast redwood reproduces asexually by sending new sprouts up from the trunk base of a parent redwood. The mystery was whether these sprouts are genetically identical copies of the parent redwood. Because 95 percent of the current coast redwood range is younger forests, understanding the genetics of the coast redwood is critical for conservation and restoration.

Jays’ Appetite for Human Food Threatens Murrelets

A five-year study led by Elena West and Zachariah Peery from the University of Wisconsin, and sponsored by Save the Redwoods League and other organizations, has proven that Steller’s jays’ appetite for human food is a major problem. Learn more about this research.

Thinning Stands Boosts Wildlife Diversity

For many years, selective thinning has been considered a potential tool for accelerating old-growth forest characteristics in the dense stands of young trees that typically cover harvested redwood lands. Now, research by the US Forest Service has confirmed the wisdom of thinning, or removing select trees to reduce competition in a stand. Learn more about this research.

Lower Genetic Diversity Puts Giants at Risk

Recent League-funded research by Richard Dodd, an Environmental Science Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, confirms that northern groves (north of the Kings River drainage) have lower genetic diversity than central and southern groves. This could have profound consequences for long-term conservation strategies for the species, especially considering the changing global climate.

Genes Could Influence Trees’ Conservation

Genetic profiles of specific coast redwood strains mean some trees could demonstrate greater resilience in certain types of climatic conditions than others.

Seeking Elusive White-Footed Voles

The League funded an ambitious study to learn more about white-footed voles. Unfortunately, they’re almost impossible to find in the luxuriant understory of the typical coastal redwood forest. In response, researchers have released the hounds.

Fire Intensity Likely Higher in Forests Hit by Sudden Oak Death

Both as shrubs and mid-sized trees, tanoaks are an important element in Central California’s coast redwood forests. They add structural diversity and, through their acorns, abundant food for wildlife. Afflicted by the disease “sudden oak death” (SOD), they may soon be adding fuel to coastal fires. Learn more about this research.

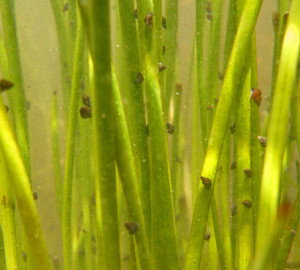

Snail Invasion Could Mean Trouble for Food Web

Humboldt State University fisheries biologist Darren Ward was concerned, but not surprised, when New Zealand mud snails showed up in Redwood National Park in 2009. With help from a grant from Save the Redwoods League, Ward and a colleague at the US Geological Survey, Adam Sepulveda, began searching to see if they were moving upstream. Learn more about this research.

Redwood Forest Edges Offer Habitat for Evolution

Though common in chaparral, manzanitas can also eke out a living on the edges of coast redwood forests. A recent study funded by Save the Redwoods League explored the differences between coastal versions of this sturdy red-barked shrub and their more sun-loving cousins.

Deciduous Ferns May Hold Advantage as Climate Changes

In 2010, funded by Save the Redwoods League and the National Science Foundation, Professor Jarmila Pittermann and Burns began a study comparing the leaves of evergreen and deciduous ferns. Interested in their response to drought, they chose midsummer, just before the deciduous ferns would shed their leaves, in the drier southern part of coast redwoods’ range (in the Santa Cruz Mountains and Big Sur). They expected that evergreen leaves, which are thicker, would show fewer signs of water stress.

Small Giant Sequoia Groves May Not Endure

More than 30 years ago, giant sequoia seeds were collected in 23 groves representing the species’ range from north to south in the Sierra Nevada. They were propagated and planted on US Forest Service land 20 miles east of Auburn, California, that was hotter, drier, lower in elevation and farther north than any of their original homes. This experiment, the legacy of William J. Libby, UC Berkeley emeritus professor and Save the Redwoods League board member, has been studied and carefully maintained ever since.

Promoting Giant Sequoia Regeneration

Giant sequoias can live for thousands of years, but they sometimes have difficulty getting started. Unlike coast redwoods, giant sequoias rarely sprout from their bases. Their reproductive future lies in their tiny (0.2-inch-long) seeds, which need just the right combination of soil, sun and moisture to survive.

Redwood Forest Restoration and Martens

Martens are agile, 2-foot-long members of the weasel family. They need ancient forests—and used to thrive in the coast redwoods of California. Today the Humboldt marten, the coastal subspecies of the Pacific marten in California, has vanished from more than 95 percent of its former range. A single population of about 100 remains on the coastal edge of the Six Rivers National Forest, roughly between Crescent City and Arcata. Learn more about this research.

New Links in Food Chain of Giant Sequoia Forest

Funded by a grant from Save the Redwoods League, entomologist Peter H. Kerr recently found two new species of fungus gnats near the base of some of the park’s giant sequoias. Learn more about this research.

Disturbances Benefit Giant Sequoias

Being dwarfed by Earth’s most massive tree, the giant sequoia (aka “Sierra redwood”), fills you with wonder. It’s hard to believe that a living thing can be so enormous and old. It may be alarming to see these forests on fire, but research funded by your gifts shows that disturbances such as these actually are good for giant sequoias. Learn more about this research.

Redwood Forests May Be Crucial for Silver-Haired Bats

A US Forest Service ecologist, Weller decided to check out his own backyard: the redwood forests of Northwest California. He not only found bat activity in winter, but also important clues about the bats’ migrations. When Weller had surveyed a common species called the silver-haired bat in summer, he’d found almost all males. In the winter, however, he began to catch females right away. So he asked Save the Redwoods League to fund research to figure out what was going on. Learn more about this research.

Redwoods Regrow After Fires

In the past 70 to 80 years, most fires in California’s coast redwood forests were prevented or suppressed. But in 2008, more than 2,000 fires ignited forests in Northern and Central California during a single summertime lightning storm. Overwhelmed by conflagrations in drier areas, firefighters allowed many of fires in coast redwood forests to burn.

Forest Restoration through Thinning

For more than half a century, the Mill Creek region in Northern California produced lumber. After clear-cutting, too many seeds were planted, producing a forest in which too many young trees competed for light, water and other resources. Now, thanks to Save the Redwoods League, Mill Creek is protected as part of Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park and is becoming a laboratory for redwood forest restoration. Learn more about this research.

Redwood Soil Microbes Can Adapt to Climate

Coast redwoods need healthy soil and its tiny organisms to survive. So how will climate change affect the forests’ fungi and bacteria? A research team led by Professor Mary Firestone at the University of California, Berkeley, recently found a way to mimic what the future may hold. Learn more about this research.

Salmon Numbers Fall, But Restoration Offers Hope

Virtually all redwood forests have (or once had) streams in which salmon run and spawn. But after 150 years of damming, water diversion, logging and development, most of these fish species face extinction. Learn more about this research.

Black Salamanders Show Biodiversity of Redwood Forest

The range of the black salamander (Aneides flavipunctatus) almost perfectly overlaps with the historic range of redwoods along the Central and Northern California coast. While most animals live on the Earth’s surface, this well-hidden amphibian travels mostly up and down in the rocks and soil. Its vertical approach to life comes in handy when the weather is hot or dry: the salamander moves deeper into the Earth until conditions are more to its liking. Learn more about this research.

Tanoak Decline in Redwood Forests

Tanoak (Notholithocarpus densiflorus) grows in coastal forests in Oregon and California. Compared with the majestic redwood, it’s scruffy and small. But this humble hardwood plays an important ecological role in the redwood forest ecosystem. Its medium-height trees add a second canopy to the complex architecture of an old-growth redwood forest, creating more niches for diverse species. And its nutritious acorns feed bear, deer, rodents and birds.

Central California Redwoods More Vulnerable

Researchers found in a 2007 study that coast redwoods’ genetic diversity was “very high” throughout the state, and more divergent in Central California. These Central California redwoods are most threatened by climate change and “should be a conservation priority,” said Richard S. Dodd, a professor of plant population genetics at the University of California, Berkeley.

Examining Coast Redwood Genes

Genome science has made stunning advances in the past few decades. But until recently, no one had tried to sequence Sequoia sempervirens, the coast redwood. Part of the problem was the species’ complexity. Humans are “diploid,” meaning that for each chromosome, they have one copy inherited from their mother and one from their father. Redwoods, on the other hand, are “hexaploid,” meaning that they have three copies from each side, which triples the size of their genome.

Fog and Redwood Forest Plants

Coast redwood forests depend on fog to survive the nearly rainless summers of California’s Mediterranean climate. It was once thought that redwoods captured this moisture through their roots. But a 2004 Save the Redwoods League-funded study proved that redwoods suck up water through their leaves as well. As a doctoral student at the University of California, Berkeley, Emily Burns set out to discover whether other plants in the redwood ecosystem were equally adept at “foliar uptake.”

Pre-Logged Northern Redwood Forests

If you want to restore a logged-over redwood forest, how do you decide what should be there? In the past, land managers looked at the mix of species in nearby protected areas. But no one knew for sure whether they represented typical redwood forests—or just the ones with the most interesting or abundant redwoods. Learn more about this research.

Coast Redwoods’ Response to Disturbance Events

In 2006, Save the Redwoods League recruited eight scientists to survey scientific literature about how coast redwood forests respond to “disturbance events” such as fires, windstorms and floods. The scientists considered how redwoods fit into two broad categories of trees: those that need major disturbances to perpetuate themselves and those that don’t. The seedlings of disturbance-dependent trees germinate in open spaces, grow quickly to outcompete other vegetation and tend to form even-age stands. Species that don’t need disturbances tend to be shade tolerant, slower growing and longer lived. They usually grow in uneven-age stands.

Thinning Would Spur Old-Growth Qualities

Upland forests in Redwood National Park have been studied extensively. But until a few years ago, less was known about streamside, or “riparian,” forests, which benefit the park’s salmon habitat by providing shade, erosion control and woody debris in the streams. So Humboldt State University graduate student Emily King Teraoka decided to compare two of the park’s riparian forests: one along Lost Man Creek, which had been clearcut between 1954 and 1962; and one along Little Lost Man Creek, which was mostly untouched. Learn more about this research.

Old Redwood Forest Restoration

Old-growth redwood forests are prized for their biological and aesthetic riches. If you’re a land manager trying to restore lands where redwoods have been logged, the old-growth forest is the ideal to which you aspire. But how do you move toward old-growth characteristics most efficiently? Learn more about this research.

Fires Were Common in Rainy Northern Forests

For years, Steve Norman had been told that the humid forests of coastal Northern California must be too wet to burn. Scientists who research fire acknowledge its power as a tool for reshaping the landscape, but some areas were considered nearly immune to fire. This assumption meant that the damp forests of Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park remained a blank file in the coastal forest fire records.

Growing New Giants Through Canopy Gaps

It seems unfathomable that the tiny seedlings Rob York sowed among ash piles in a clearing at Whitaker’s Forest could someday grow to be among the largest creatures on earth. Yet these green specks grew into giant sequoias two years after seeds were strewn in canopy gaps. This species of titan tree has stagnated in regeneration efforts for nearly a century. York, along with his graduate advisor, John Battles, is working on unlocking the secrets to growing new giants. Learn more about this research.

Amphibian Populations Predict Forest Health

In a forest of towering redwoods, the small creatures scurrying underfoot and splashing into streambeds sometimes go unnoticed as visitors crane their necks toward distant treetops. We should look down, though, say researchers from the Redwood Sciences Laboratory, who visited several state parks to study the ecosystems that surround and support those mighty trees. Researchers Garth Hodgson and Hartwell Welsh pay particular attention to tiny amphibians such as frogs, salamanders, newts in redwood forests, because published studies suggest they are indicators of forest health. Learn more about this research.

Wonder Plot Study Tells Story of Development

In 1923 Emanuel Fritz, then a Professor of Forestry at UC Berkeley, and Woodbridge Metcalf secured for study a one-acre grove of second growth trees along the Big River in Mendocino County. By that year, much of California’s old-growth redwood had been logged and a second generation of trees had begun to grow. Fritz and Metcalf intended to study tree growth on their plot in order to better understand just how a second growth forest develops.

Winter habitat crucial for coho salmon, spring for Chinook

The coho salmon population in Del Norte County’s Mill Creek depends heavily on the quantity and quality of winter habitat for survival, according to a study by The Rowdy Creek Fish Hatchery and a team of fisheries biologists. Learn more about this research.

Thinning Speeds Recovery to Old-Growth

Dr. Christopher Keyes and Andrew Chittick have found that thinning—removing select trees in a second-growth coast redwood forest—speeds up the forest’s development of old-growth characteristics, which include tall and bulky trees, small gaps in the canopy through which sunlight can penetrate, trees of varying heights, thicker tree branches, understory shrubs and ferns, and healthy young saplings. Learn more about this research.

Prehistoric Fires Not Caused by Understory Grasses

Grassy fuels on the forest floor were not the cause of frequent prehistoric fires in giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) groves, according to UC Berkeley researchers and California State Park ecologists.

Land Use and Forest Conservation

Dr. Sarah Marvin, professor of Geography at the University of Oregon, has set out to understand how the shape of the land and its use by owners reflect the probability of a privately owned coast redwood forest being protected. The two questions she has asked are: “Are privately owned forests more likely to be protected if they are on bigger parcels?” and “Do traditional, rural land uses as opposed to traditional, residential land uses promote forest preservation?” Answers to these questions might help predict the likelihood of future, private redwood forest protection and—of logged forests—regeneration. Learn more about this research.

Big Trees: A Bank for Soil Bugs

Legacy trees, old-growth trees left standing in second-growth redwood forests, could serve as a habitat refuge for terrestrial microarthropods, miniscule bugs that live in the forest floor and maintain healthy soils, not to be confused with the bigger arthropods like spiders and bees. Dr. Michael Camann, Karen Lamoncha and Laura Hagenhauer have found substantially more and a wider variety of the soil bugs underneath these so-called legacy trees than beneath surrounding second-growth trees. Learn more about this research.

Bigger and Older Often Means Better Habitat

Traditionally we think of forest conservation as protection of large areas of land. Is it possible, though, that just one tree could benefit an ecosystem enough to warrant individual protection? Mary Jo Mazurek and William Zielinski report evidence that suggests legacy old-growth redwoods can do just that. Learn more about this research.

Chemicals in Redwood Rings Indicate Past Water Uptake

It’s no coincidence that redwoods live in the thickest part of “California’s fog belt.” The presence of coastal summer fog has long been regarded a necessary ingredient for the health and perpetuation of coast redwood ecosystems. During drier summer months fog supplies trees with moisture and blocks the evaporating rays of direct sunlight, reducing the amount of water that redwoods lose via transpiration. What’s less understood, however, is exactly how fog frequency has varied in the past century and how redwoods have responded to this variation.

Redwoods to the Sea Forest Carnivore Tracking Project

From time to time, a resident in Humboldt County will submit a report claiming to have spotted a Pacific fisher or a Humboldt marten. Because Pacific fishers are rare, and because the Humboldt marten was previously thought to be extinct due to human influences such as trapping and logging in their old-growth conifer habitat, these animals remain barely documented. The Corridor from the Redwoods to the Sea, built as a passageway for wild creatures, appears to be prime location to spot small carnivores such as fishers and martens, but despite local accounts, the rare sightings remain unverified by scientists. Where have these small predators gone? Learn more about this research.

Bats in Giant Sequoias

Prior to this study, little was known about the bat community in Yosemite’s three giant sequoia groves and virtually nothing was known about how bats use the canopy in any of the Parks’ forests. Dr. Elizabeth Pierson, Dr. William Rainey, and Leslie Chow carried out major research to study bat roosting behavior in fire-scarred hollows at the base of sequoia trees, bat feeding behavior in association with a variety of habitats, and bat activity in the giant sequoia canopy. In addition, they combined observations from this study and others to describe the natural history of Yosemite’s 18 bat species. Learn more about this research.

Sponge-like Mats Make Good Habitat in Redwood Canopies: Wandering Salamanders Benefit

Based on their research in Pairie Creek Redwoods State Park, Anthony Ambrose and Stephen Sillett have found that mats of humus soil deposited as high up as 265 feet in the crowns of coast redwood trees moderate the climate around them. This makes the mats habitable to a wide variety of insects and animals more commonly found on the forest floor. Learn more about this research.

What limits redwood height?

In the upper reaches of their crowns, coast redwoods struggle to lift water and nutrients into their leaves. This struggle begins a process that limits tree growth, according to a team of researchers studying redwoods in Prairie Creek and Humboldt Redwoods State Parks.

Wandering Salamanders Choose Direct Route to Good Food

Wandering Salamanders (Aneides vagrans), in addition to dwelling on the ground, have been found in high-up patches of humus moss mats in trunk crotches, on limbs, under bark, and in the cracked and rotting wood of coast redwood trees. They may inhabit forest canopies, the researchers of this study speculate, because of a more profitable food resource available there. Learn more about this research.

Humboldt Martens Need Old Growth

It’s likely that Pacific fisher (Martes pennanti pacifica) populations are well distributed in Northern California’s Redwood National and State Parks (RNSP) for the same reason that Humboldt martens (Martes americana humboldtensis) have disappeared, according to research done by Keith Slauson, William Zielinski, and Gregory Holm. Second-growth forest habitats that cover a majority of the park are fishers’ sweet and martens’ sour. Learn more about this research.

Buffer and Let Be

Dr. William Russell found that the negative effects of timber harvesting in riparian coast redwood forests lessen with respect to two conditions; (1) longevity of the forest and (2) wider no-cut buffer zones. Longer-lived forests and forests with wider buffer zones surrounding rivers show less harm from logging. Riparian buffers are strips of forest left on either side of rivers after logging that control the amount of sediment and nutrients filtering into the water. In recently harvested forests and ones with thin or no buffers, young tree crowns crowd the canopies, letting through less sunlight, deciduous hardwoods thrive, extra dead wood litters the forest floors, and exotic and disturbance-prone understory species invade. These alterations, in addition to affecting the physical structure of rivers, down the line cause higher levels of organic material to filter into them. Learn more about this research.

Balanced Management of Giant Sequoias

Giant sequoias are sometimes simply referred to as “big trees” and with good reason: They are the largest trees by volume and among the largest living things on Earth. These massive trees do not function in a void; they are supported by an intricate network of natural processes that keep the ecosystem working properly.

Bigger Preserves Have Better Chance to Prevail

Dr. William Russell, Dr. Joe McBride, and Ky Carnell have found that old-growth coast redwood forest reserves with areas larger in proportion to the length of their perimeters suffer fewer negative effects from exposed edges. Learn more about this research.

Epiphytes Provide High-Up Base for Biodiversity

William Ellyson and Stephen Sillett found evidence that demonstrates that epiphytes—plants that use other plants for mechanical support—play a crucial role in maintaining the biodiversity of redwood forest canopies. It’s well known that these hangers-on thrive in the old-growth Douglas-fir forests of Oregon and Washington, in places amassing the weight of two concert grand pianos per acre. Ellyson and Sillett reveal in this study that Douglas-fir has a rival in Sitka spruce, a tree that grows in and among northern coast redwood forests and supports a shockingly high diversity of epiphytes.

Coast Redwood May be the Descendent of Two

Dr. Raj Ahuja and Dr. David Neale have taken a big stride in coming closer to knowing the origin of polyploidy in coast redwood.

Bibliography Provides Easy Access to Coast Redwood Research

Coast redwoods have captivated scientists since their discovery, and thousands of articles, dissertations, and books have been written in an attempt to decipher various aspects of these magnificent trees. Finding all of this information was considerably more challenging until Deborah Rogers, a research geneticist and conservation biologist with the Genetic Resources Conservation Program at the University of California, Davis, stepped in to organize a bibliography of scientific materials written about coast redwoods in the past 50 years.